- Date:

- 5 Dec 2022

This is the fifth of seven topic-based reports, as outlined in the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor's plan for 2021–2022.

This report examines government implementation progress in enabling Aboriginal communities to drive self-determined or ‘Aboriginal-led’ activities to prevent family violence in and against Victoria’s Aboriginal communities.

Monitoring Victoria’s family violence reforms: Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention

Monitoring context

About the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor (the Monitor) was formally established in 2017 as an independent statutory officer after the Royal Commission into Family Violence released its report in 2016. The role is responsible for monitoring and reviewing how the government and its agencies deliver the family violence reforms as outlined in its 10-year implementation plan Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan for Change.

On 1 August 2019 former Victorian Corrections Commissioner Jan Shuard PSM was appointed as the Monitor under section 7 of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor Act 2016. Jan took up her role on 2 October 2019, replacing Tim Cartwright APM, the inaugural Monitor.

Monitoring approach

The Monitor’s 2021–2022 plan was developed through a process of consultation with government and sector stakeholders. Topics were selected that aligned areas of greatest interest and concern to sector stakeholders, with reform implementation activity outlined in the government’s second Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023. In determining topics, the focus was on areas where an independent perspective could add the most value to the ongoing reform effort.

Topics selected for monitoring throughout 2021 and 2022 are:

- accurate identification of the predominant aggressor

- family violence reform governance

- early identification of family violence within universal services

- primary prevention system architecture

- Aboriginal-led primary prevention and early intervention (this report)

- crisis response to recovery model for victim survivors

- service response for perpetrators and people using violence within the family.

In undertaking our monitoring, the following cross-cutting themes are examined across all topics:

- intersectionality

- children and young people

- Aboriginal self-determination

- priority communities such as LGBTIQ+, people with disabilities, rural and regional, criminalised women, older people and refugee and migrant communities

- data, evaluation, outcomes and research

- service integration.

Monitoring of the selected topics is based on information gathered through:

- consultations with government agency staff

- consultations with community organisations and victim survivor groups

- site visits to service delivery organisations (where possible within COVID-19 restrictions)

- attendance at key governance and working group meetings

- documentation from implementation agencies, including meeting papers and records of decisions by governance bodies

- submissions made to the Monitor in 2020 by individuals and organisations (many of these are available in full on the Monitor’s website).

Engaging victim survivors in our monitoring

We are also actively seeking to include user experience and the voices of victim survivors in our monitoring. The office is working with established groups including the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, Berry Street’s Y-Change lived experience consultants and the WEAVERs victim survivor group convened by the University of Melbourne.

Stakeholder consultation

The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor would like to thank the following stakeholders for their time in monitoring this topic:

- Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS)

- Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service

- Dardi Munwurro

- Department of Education and Training

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (including Family Safety Victoria)

- Department of Justice and Community Safety

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus

- Djirra

- Gippsland and East Gippsland Aboriginal Corporation

- Inner Gippsland and Outer Gippsland Dhelk Dja Action Group representatives

- Koorie Youth Council

- Mallee Dhelk Dja Action Group

- Mullum Mullum Indigenous Gathering Place

- Oonah Health and Community Services

- Our Watch

- Respect Victoria

- Safe and Equal

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Ltd

- Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Inc.

- Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service

- Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council

- Wathaurong Aboriginal Cooperative

- Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service.

In addition to the many individuals and organisations who contributed to our monitoring, we would like to acknowledge the assistance of:

- Karen Milward, a Yorta Yorta consultant who we engaged to support our office in undertaking this topic

- an Aboriginal victim survivor who we engaged to ensure the victim survivor perspective was represented in our work

Karen’s and the victim survivor’s expertise and guidance were invaluable for our non-Aboriginal staff in properly hearing, understanding and reflecting the views of Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations and community members for this report.

Monitor’s foreword

Jan Shuard PSM

Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

The Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus chose this topic, and it is easy to see why it was a priority, principally because it is integral to family violence practice in Aboriginal communities. Grounded in cultural strengthening, cultural expertise and education, this strengths-based approach is embodied in Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families and is embedded in the Aboriginal service system. The strategy is to intervene early to address the many causal factors that can lead to family violence. This holistic approach does not fit neatly into the mainstream structures and as such sometimes important work is unrecognised. However, as impressed on us by the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, self-determination is a non-negotiable must for government; it is the foundation for all work with Aboriginal people.

This report highlights the prevention and early intervention work delivered by Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, Dhelk Dja Committees, and local workforces and networks and how this is culturally unique and done differently from mainstream approaches. In shining a light on this topic, this report examines the implementation of the relevant recommendations from the Royal Commission into Family Violence to assess whether the full potential of Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations to prevent and respond to family violence is being realised.

Universally, Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations we consulted told us that prevention of family violence in community is grounded in healing, identity, culture, connection and strengthening families. However, there is a disconnect between this approach and mainstream practice and the funding frameworks and reporting requirements that sit around them. Because funding of programs is largely short-term and may not always include sufficient time or provision for implementation and culturally appropriate evaluation models, the outcomes cannot be demonstrated to the extent that they should be, therefore the true value is likely underestimated.

Our heartfelt thanks go to all the people who generously gave their time to share their knowledge and expertise on this topic. I trust this report reflects that we listened and heard their stories. We were expertly guided through this review by Karen Milward, a proud Yorta Yorta woman, who ensured our consultations were culturally safe; and an Aboriginal victim survivor who contributed her lived experience expertise and perspective to our monitoring. Members of the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus have also supported this review with their skilful guidance and expertise.

There can be no doubt that Aboriginal people know best what is right for their communities and must be supported to provide the best services for their people. However, the same obligations rest with the state and mainstream services to hear the voices of Aboriginal people and provide culturally safe and appropriate prevention and early intervention efforts.

Victoria is privileged to have such an abundance of committed, competent and passionate Aboriginal people working in the family violence sector – these are the champions and strategic leaders who work tirelessly for their communities. Their individual and collective strength and willingness to go above and beyond is to be revered. Many Aboriginal people we spoke to have been involved in tackling the causes of family violence in Aboriginal communities for more than 20 years, since the Victorian Indigenous Family Violence Task Force released its report and recommendations to the Victorian Government. These are true leaders in their field, and the suggested actions in this report are based on what they see as important to improve the implementation of the Royal Commission’s recommendations to prevent and intervene early to reduce the harm of family violence.

The starting point must be to define and agree what constitutes prevention and early intervention in Victorian Aboriginal communities and what are meaningful outcomes and measures. This is for Aboriginal people to decide but they require the resources, funding and supports to do this work.

Jan Shuard PSM

Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way - Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families artwork

Source: Family Safety Victoria. Artist, Trina Dalton-Oogjes.

Artwork and Artist

Trina Dalton-Oogjes is a proud Wadawurrung/Wathaurung woman. Trina’s painting centres around the eleven community Dhelk Dja Action Groups across Victoria, leading into a central gathering/yarning circle, empowering Aboriginal communities based on a healing and trauma informed process, to lead collaborative partnerships through a culturally safe service system.

Around the eleven community Dhelk Dja Action Groups are Aboriginal organisations/agencies, government departments and non-government agencies working together to address family violence.

Bunjil the Creator oversees to empower strength and self-determination. Hand prints of the adults and children represent the family unit. The kangaroo and emu footprints represent partnership moving forward (kangaroos and emus only move forward).

Introduction

In establishing our 2021–2022 monitoring plan, we committed to including a topic focused on family violence reform progress for Victoria’s Aboriginal communities. In this report, an Aboriginal definition of family violence is used, as described on page 9. In the spirit of self-determination, we asked the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus – the Aboriginal communities’ governing body for Victoria’s family violence reform – to choose which area of the reform they wanted us to examine.

Following a process of consultation, including a survey of caucus members on a shortlist of topics, 'Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention' was selected. We received guidance from the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus in developing our key questions and monitoring approach for this topic and the caucus also contributed to informing our key findings and suggested actions.

As all stakeholders emphasised – including the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA), a major provider of Aboriginal family violence services in Victoria – the principle of self-determination must underpin all prevention and early intervention activities within Aboriginal communities. VACCA more broadly recommended that our report incorporate binding principles on government around self-determination to guide this critical work and that these should be negotiated with Aboriginal family violence service providers directly. While this report does not address this specifically, the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2018–2023 outlines self-determination principles, and there is an opportunity for government to work with Aboriginal family violence service providers as part of the next iteration of the framework to strengthen its implementation.

This report examines government implementation progress in enabling Aboriginal communities to drive self-determined or ‘Aboriginal-led’ activities to prevent family violence in and against Victoria’s Aboriginal communities.

In looking at this topic, we set out to examine:

- the government and non-government frameworks that guide primary prevention efforts within Aboriginal communities and how they intersect with broader frameworks across the primary prevention sector

- coordination of effort across government and Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) and how these organisations are supported to deliver prevention and early intervention initiatives in their communities, including the approach to funding

- the availability of data and evaluation outcomes to Aboriginal communities and how they are being used to guide prevention and early intervention efforts

- how government services are accountable to Aboriginal communities for delivering responses to prevent family violence in and against Aboriginal people and their families.

We acknowledge the long history of community-led effort to prevent and address family violence in Aboriginal communities in Victoria. ACCOs and community leaders have demonstrated huge commitment to working with their communities in an integrated, prevention-focused way that prioritises family and building connection with culture and identity.

In the context of enormous pressure on services and ACCOs, and at a time of considerable demand for consultation with Aboriginal communities, the assistance we received was both humbling and critical to our ability to deliver this report.

Language in this report

As the focus of this report is on family violence efforts in Victoria, we refer to Aboriginal people and communities rather than to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This is not intended to convey that Torres Strait Islanders are excluded from family violence prevention and response delivery. Indeed, we acknowledge the inclusive nature of family violence work within Victoria’s Aboriginal communities.

There is a broader definition of family used by Aboriginal communities that goes beyond the Western concept of the nuclear family. As Aboriginal communities are often composed of extended families and kinship networks whose members are not always blood relations, there is a wider definition to mirror the family structure. The Victorian Indigenous Family Violence Task Force report identified family violence as ‘an issue focused around a wide range of physical, emotional, sexual, social, spiritual, cultural, psychological and economic abuses that occur within families, intimate relationships, extended families, kinship networks and communities. It extends to one-on-one fighting, abuse of Indigenous community workers as well as self-harm, injury and suicide.’

Within Aboriginal communities there is not a strict delineation made between prevention and early intervention (or indeed response) because:

… for Aboriginal people, we are yet to be free from violence in any sphere of our lives and this endures since colonisation … the adaptability and flexibility in applying Aboriginal ways of knowing, doing and being will require prevention and early intervention to remain interchangeable in practice - VACCA

Indeed, Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service explained how its therapeutic services arose out of their existing community prevention work. In undertaking community family violence education, community members would say ‘that’s what I’m experiencing’, which led Yoowinna Wurnalung to develop a therapeutic response to address the healing needs of the community.

Noting this approach, throughout this report we use the terms ‘prevention’ and ‘early intervention’ as described in the Free From Violence strategy and depicted in Figure 1. A further description of the distinct understanding of and approach to prevention and early intervention within Aboriginal communities is provided in Box 2 (later).

The importance of prevention and early intervention within Aboriginal communities

While family violence is an urgent issue impacting every community in Victoria, Aboriginal people continue to be disproportionately affected. In the 12 months to March 2022, just over 2,800 Aboriginal Victorians (approximately 4.3 per cent of the state’s Aboriginal population1 compared with approximately 1.3 per cent of Victoria’s non-Aboriginal population) were recorded by Victoria Police as victims of family violence. This likely does not reflect the true prevalence due to the hidden nature of family violence for all communities and continued reluctance, particularly among Aboriginal communities, to report matters to police.

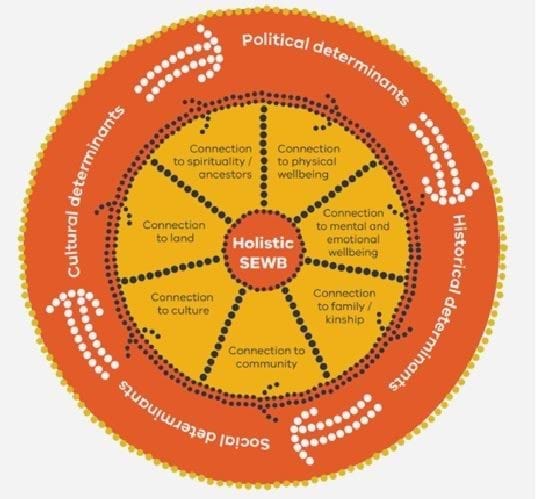

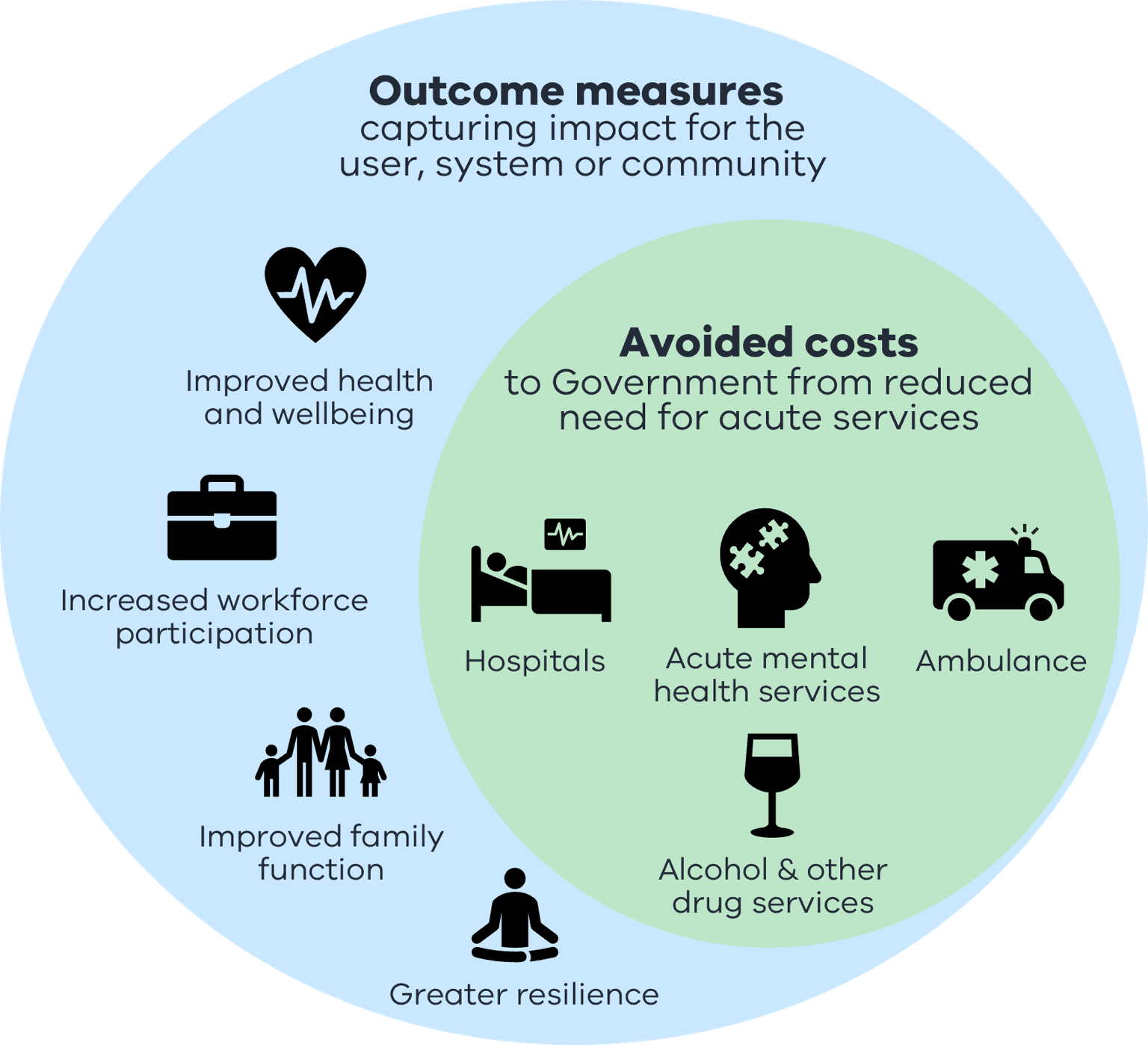

It is important to acknowledge that family violence and violence against women are not a part of Aboriginal culture, and that violence against Aboriginal people is perpetrated by both non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal people. It is, therefore, a problem not just for Aboriginal communities but for the whole of our society to address. It is also worth noting the many complex drivers of this violence includes not only gender inequality but also the ongoing impacts of colonisation and racism.2 The trauma of family violence has profound negative impacts on the health and wellbeing of those who are victims of it (see Figure 2, for example), and many of these impacts are heightened for Aboriginal people:

- Aboriginal women and men are more likely to be hospitalised for assault injuries due to family violence than non-Aboriginal women and men respectively.

- Aboriginal women are more likely to be killed as victims of family violence than non-Aboriginal women.

- Family violence is the number one risk factor for disease burden among women aged 18–44 years and is higher for Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal women.

- Family violence is a key factor in the removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

While responding to violence that has occurred and working to prevent it from reoccurring is important, government also has an obligation to actively pursue the prevention of violence before it starts, as it does with a range of factors that cause harm to the population. Both prevention and response are part of a spectrum of required activity, which includes primary prevention, early intervention and response (see Figure 1 above). The criticality of prevention and early intervention for Aboriginal communities was reflected in submissions to the Royal Commission, as illustrated by the chief executive officer of the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation:

These preventative and early intervention programs are actually the most important part, if we truly want to get violence out of our community, keep families together and give kids the best start in life that we can.

The interrelationship between family violence and broader health and wellbeing outcomes for Aboriginal people – as illustrated in Figure 2 – means that focused efforts to prevent family violence and to intervene early remain as important as ever. This is particularly true given Victoria’s high rates of removal of Aboriginal children, where family violence is a key factor.

Consistent with the principles of self-determination, Aboriginal consultant Karen Milward advised that the overall approach to reducing the impact of family violence on Aboriginal communities must be Aboriginal-led and solutions-focused. The approach must be informed by the experiences and history of Aboriginal people, including children and young people, and address the family unit as a whole as part of a holistic, trauma-informed approach.

The remainder of this report examines the progress that has been made since the Royal Commission in supporting Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention efforts and identifies areas for further focus.

Footnotes

- According to the 2021 census, 66,000 Victorians identify as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. See Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022): Snapshot of Australia: A Picture of the Economic, Social and Cultural Make-up of Australia on Census Night, 10 August 2021

- For example, the Health and Wellbeing of Aboriginal Victorians: Findings from the Victorian Population Health Survey 2017 reported that 18.8 per cent of Aboriginal adults experienced racism in the 12 months preceding the survey, that Aboriginal adults under-report racism, and that experiencing racism is associated with poorer wellbeing and physical health.

Key findings and suggested actions

Victoria’s Aboriginal communities have a long history of efforts to prevent family violence, and we have seen some excellent examples of community-led prevention and early intervention work. We heard about the unique approach to prevention in Aboriginal communities, which includes:

- being fully integrated with early intervention and response and recovery work

- focusing on healing through cultural strengthening, connection to Country and community and strengthening cultural identity

- aiming at broad community health and wellbeing outcomes (of which family violence may be only one).

We also heard consistent messages about the impact of short-term funding on the ability of organisations to deliver effective and sustainable initiatives – and the flow-on impacts of this for staff and communities.

Government has invested substantially in family violence services in Aboriginal communities since the Royal Commission and has supported a wide array of community-led prevention and early intervention initiatives through grants-based funding. While much progress has been made, many of the issues raised by the Royal Commission remain and emerged as strong themes in our consultations. These themes form the section headings in this report:

- There is a wide range of effective prevention and early intervention initiatives being led by Victorian Aboriginal communities.

- There is a need for a more sustained approach to support Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations to apply frameworks and evaluate the outcomes of initiatives.

- A continued reliance on short-term, grant-based funding is undermining prevention and early intervention efforts.

- More culturally adapted capacity-building opportunities are needed to support the Aboriginal prevention workforce.

- Government accountability for the delivery of initiatives to support Dhelk Dja priorities could be strengthened.

The report provides our detailed analysis and findings that directly relate to the suggested actions outlined in Figure 3. These actions are also highlighted throughout the report.

Figure 3: Proposed actions to support Victoria's Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention

Aboriginal Prevention Framework

- In updating the Aboriginal primary prevention framework, develop a corresponding theory of change and strategic operating framework to guide future primary prevention efforts in the Aboriginal community, and to complement work to support the broader primary prevention system architecture.

Long-term Funding and Funding Reform

- Commit to ongoing base funding for Aboriginal prevention and early intervention – with longer-term funding agreements with ACCOs for delivery of initiatives to provide certainty and sustainability, and that include adequate funding to support data collection, monitoring, and evaluation.

- Prioritise cross-government funding reform that moves to single funding agreements and streamlined, outcomes-based reporting; and in the interim, ensure that funding reform work being undertaken within individual departments is coordinated and aligned.

Workforce Support to Apply Frameworks and Evaluate Initiatives

- Consider how to build capability within the ACCO sector to tailor and apply prevention frameworks, and support organisations to monitor and evaluate prevention and early intervention initiatives, including whether a model such as the Bailt Durn Durn Centre of Excellence would be an effective approach.

Data to Support Strategic Decision Making

- Government to ensure that regular and up to date data is provided to support Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus to make strategic decisions about family violence prevention and early intervention priorities, including on:

- family violence incidents and drivers

- availability and spread of existing initiatives across regions

- program delivery outputs and outcomes.

Government Accountability

- In developing the next Dhelk Dja action plan, government departments and agencies commit to how they will deliver on Dhelk Dja’s priority areas and ensure their accountability for the agreed actions through the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum.

- Identify priority actions for departments and agencies to undertake to address racism and discrimination as drivers of family violence (an outstanding action from the first action plan) as part of implementing action 6 above.

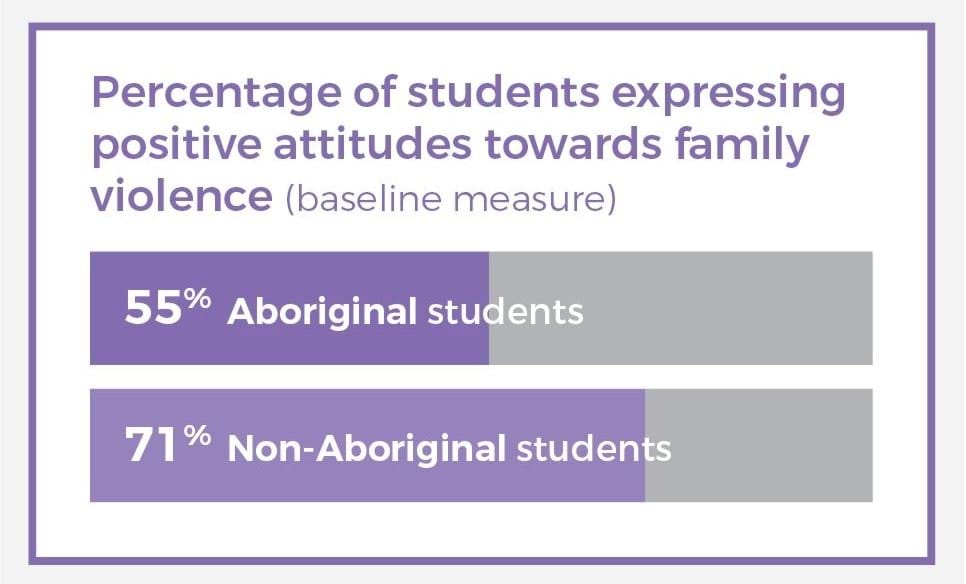

- The Department of Education and Training work with the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus to ensure that Respectful Relationships education in schools is implemented in a culturally appropriate manner and is effective for Aboriginal students, for example through the provision of additional materials or resources for schools or other mechanisms as needed.

What did the Royal Commission say and what has changed since?

The Royal Commission into Family Violence acknowledged the high rates and devastating impacts of family violence within Aboriginal communities. It also found that the:

... full potential of Aboriginal community controlled organisations to prevent and respond to family violence has not been realised.

In making this finding, the Royal Commission referenced the strong policy foundations provided by the [then] Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families: Towards a Safer Future for Indigenous Families and Communities 10-Year Plan 2008–2018 (the predecessor to the Dhelk Dja 10-year agreement) and the work of the Indigenous Family Violence Task Force. It also identified factors that had impeded progress including:

- a lack of funding and short-term funding undermining efforts – particularly for prevention and early intervention

- insufficient investment in evaluation to better target efforts

- inadequate data collection by mainstream (i.e. non-Aboriginal-led) agencies to inform Aboriginal-led efforts

- a need to ensure Aboriginal people can choose whether to access Aboriginal or mainstream services and to ensure ACCOs are able to support Aboriginal communities.

The Royal Commission recognised that in working to address family violence:

… it is crucial to understand family violence as emerging within the context of deep intergenerational trauma as a result of colonisation, dispossession and the destructive impact of policies and practices such as the forced removal of children. There is no doubt that for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, culture is the foundation upon which everything else is built and that strong cultural identity and connection is key to better outcomes.

The Royal Commission made several recommendations that relate to primary prevention and early intervention in Aboriginal communities.1 These recommendations included the need for government to:

- implement recommendations of the mid-term evaluation of the Indigenous Family Violence 10-Year Plan, which included establishing an additional stream of ongoing funding to support family violence responses in Aboriginal communities (including the continuation of initiatives tested through the Community Initiatives Fund)

- provide adequate funding to ACCOs for (among other things) early intervention and prevention efforts, including ‘whole-of-community activities and targeted programs’

- ensure family violence awareness and prevention campaigns reflect the diversity of the Victorian population, including Aboriginal Victorians, and are developed in close consultation with communities

- develop a strategic approach to ‘improving the lives of vulnerable Aboriginal children and young people’ in partnership with Aboriginal communities

- improve the collection and sharing of Aboriginal-specific data in the family violence area by government for use by Aboriginal communities, organisations and governance forums to inform responses at the local, regional and statewide levels

- employ evaluation models that use culturally appropriate measures and methodologies, and support to ensure Aboriginal service providers have the capacity to support culturally appropriate evaluations within their organisations.

Since then, government’s approach to implementing these recommendations has been set out through a considerable number of plans, strategies and commitments (see Figure 4). For example (in order of release date):

- Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan for Change (2016) commits to:

- delivering a dedicated prevention agency

- a statewide primary prevention strategy

- a complementary 10-year Aboriginal family violence plan

- strengthening the operation of the Indigenous Family Violence Partnership Forum (now the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum).

- Free From Violence: Victoria’s Strategy to Prevent Family Violence and all Forms of Violence Against Women (2017) acknowledges that preventing family violence against Aboriginal people and their communities requires community-led, holistic healing approaches and ‘addressing the drivers of violence that lead to institutional discrimination and racism’. The strategy is being implemented through a series of action plans, which include specific commitments for prevention efforts in Aboriginal communities:

- Free From Violence – First Action Plan 2018–2021 committed to a major behaviour change campaign with a specific focus on preventing family violence for Aboriginal people;2 and supporting the development and trialling of new approaches to prevention led by Aboriginal communities, including providing funding for workforce capacity building.

- Free From Violence – Second Action Plan 2022–2025 reiterates a commitment to self-determination and outlines five actions aligned with Dhelk Dja (see below).

- Building From Strength: 10-Year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and Response (2017) outlines a high-level vision of a highly skilled prevention workforce that strengthens the ability of the system to address the drivers of all forms of family violence and work at the population level. The industry plan included an immediate action to pilot ‘a model of embedding primary prevention expertise to work with the LGBTI, seniors and Aboriginal sectors to build primary prevention capacity and capability’.

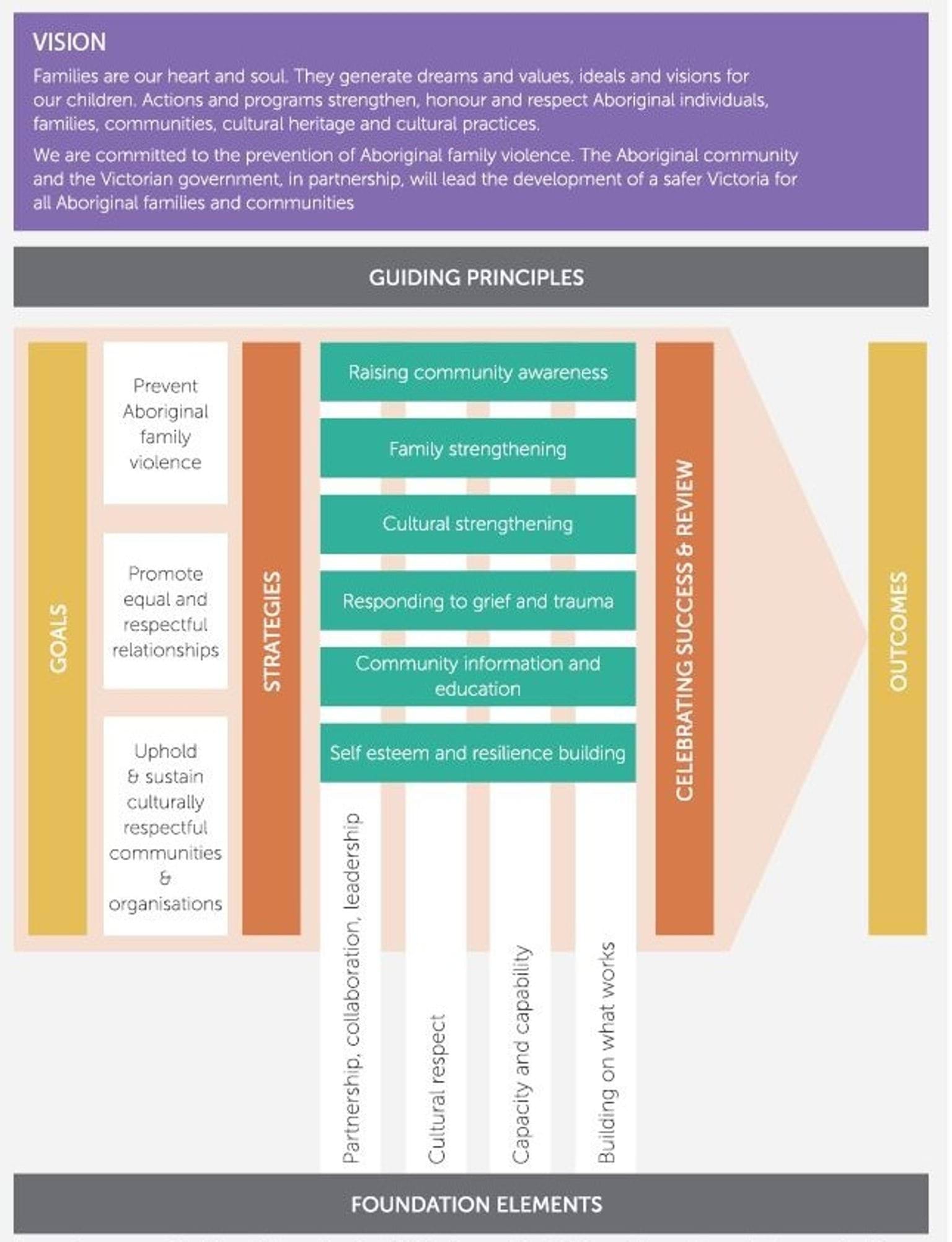

- Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families Agreement 2018–2028 is the guiding strategy and principal agreement between the Victorian Government and Aboriginal communities to address family violence. The agreement sets out five strategic priorities to be progressed through three successive action plans and assessed through a monitoring, evaluation and accountability plan. Strategic priority 2 is Aboriginal-led prevention and outlines a vision that ‘all prevention and early intervention initiatives will be led by Aboriginal communities and based on their choices and their solutions’.

- Dhelk Dja 3 Year Action Plan 2019–2022 is the first of the action plans and sets out two critical actions and seven supporting activities to be delivered under priority 2: Aboriginal-led prevention, including:

- mapping Aboriginal-specific primary prevention initiatives and investment

- showcasing successful initiatives to share best practice

- reviewing and updating the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework (2012)

- developing and delivering a prevention campaign and education program for Aboriginal communities

- sustainable investment for successful Aboriginal-led prevention initiatives

- ensuring initiatives to prevent family violence address racism and discrimination against Aboriginal people as drivers of family violence.

- Dhelk Dja 3 Year Action Plan 2019–2022 is the first of the action plans and sets out two critical actions and seven supporting activities to be delivered under priority 2: Aboriginal-led prevention, including:

- Wungurilwil Gapgapduir: Aboriginal Children and Families Agreement (2018) is a partnership between Aboriginal communities, government and community services organisations. It commits to a strategic approach to improving outcomes for Aboriginal children and young people and was developed in response to recommendation 145 of the Royal Commission.

- Nargneit Birrang – Aboriginal Holistic Healing Framework for Family Violence (2019) establishes a shared understanding of holistic healing for Aboriginal communities to guide the delivery and evaluation of Aboriginal-led holistic healing programs for family violence in Victoria. It was developed through an Aboriginal-led, co-design process with Aboriginal communities.

There are also several related government strategies and agreements that are not specific to family violence prevention and early intervention but relate to the wellbeing of Aboriginal people, families and communities more broadly and intersect with family violence prevention activity:

- Aboriginal Justice Agreement is a long-term partnership between Aboriginal communities and the Victorian Government that seeks to improve justice outcomes for Aboriginal people. Prevention and early intervention of family violence are identified under Outcome Domain 1 of Burra Lotjpa Dunguludja (Aboriginal Justice Agreement Phase 4) – Strong and safe Aboriginal families and communities.

- Balit Murrup: Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Framework 2017–2027 is a framework forming part of the Victorian Government’s commitment to improving the social and emotional wellbeing and mental health outcomes for Aboriginal communities. In Domain 2 of the framework – Supporting resilience, healing and trauma recovery – actions relating to improving connection to community, cultural strengthening and will intersect with family violence prevention activity.

- Korin Korin Balit-Djak: Aboriginal Health, Wellbeing and Safety Strategic Plan 2017–2027 is an overarching framework to improve the health, wellbeing and safety of Aboriginal Victorians. Increasing access to Aboriginal community-led family violence prevention and support services is a priority under Guiding Principle 4 of the framework – Safe, secure and strong families and individuals.

- Closing the Gap Partnership Agreement (2019–2029) is the national agreement between the Commonwealth, state and territory governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peak organisations committing to action to closing the gap in life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians across 17 socioeconomic areas. The Victorian Closing the Gap Implementation Plan 2021–23 outlines how Victoria will meet its Closing the Gap commitments, including reducing the rate of all forms of family violence and abuse against Aboriginal women and children by at least 50 per cent.

- The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System interim (2019) and final reports (2021) identified the urgent need to address mental illness in Aboriginal communities and the central role of self-determined Aboriginal social and emotional wellbeing services in promoting Aboriginal social and emotional wellbeing.

- Mana-na woorn-tyeen maar-takoort (every Aboriginal person has a home): Victorian Aboriginal Housing and Homelessness Framework (2020) aims to address homelessness and improve housing for Aboriginal Victorians. It recognises that those experiencing or using family violence are at a higher risk and therefore need specialist and intensive housing, community support and pathways.

- Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2018–2023 is the Victorian Government's overarching framework for working with Aboriginal Victorians, organisations and the wider community to drive action and improve outcomes. It commits government to reduce the incidence and impact of family violence affecting Aboriginal families (objective 3.1), with the goal being for Aboriginal families and households to thrive. It also sets out the whole-of-Victorian-Government self-determination enablers and principles and commits government to significant structural and systemic transformation.

Guiding primary prevention efforts are two specific frameworks for Aboriginal family violence prevention – one Victorian and the other national:

- Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework (2012) predates the Royal Commission. The framework’s development was led by the Dhelk Dja Action Groups formerly known as the Indigenous Family Violence Regional Action Groups. It identifies best practice features of primary prevention in Aboriginal communities and was designed to support prevention capacity building in Victoria. A refresh of the framework is a key commitment under the first Dhelk Dja Action Plan and Victoria’s Closing the Gap implementation plan and was due for completion by December 2021. At the time of writing, the refresh of the framework was in the early stages of planning.

- Changing the Picture (2018) was developed by Our Watch and provides a specific national framework to drive the prevention of violence against Aboriginal women and their children across Australia; it sits alongside the overarching Change the Story framework and resources. It includes specific actions needed to address the complex drivers of violence against Aboriginal women and their children.

A timeline of key strategies, plans and agreements is provided as Figure 4.

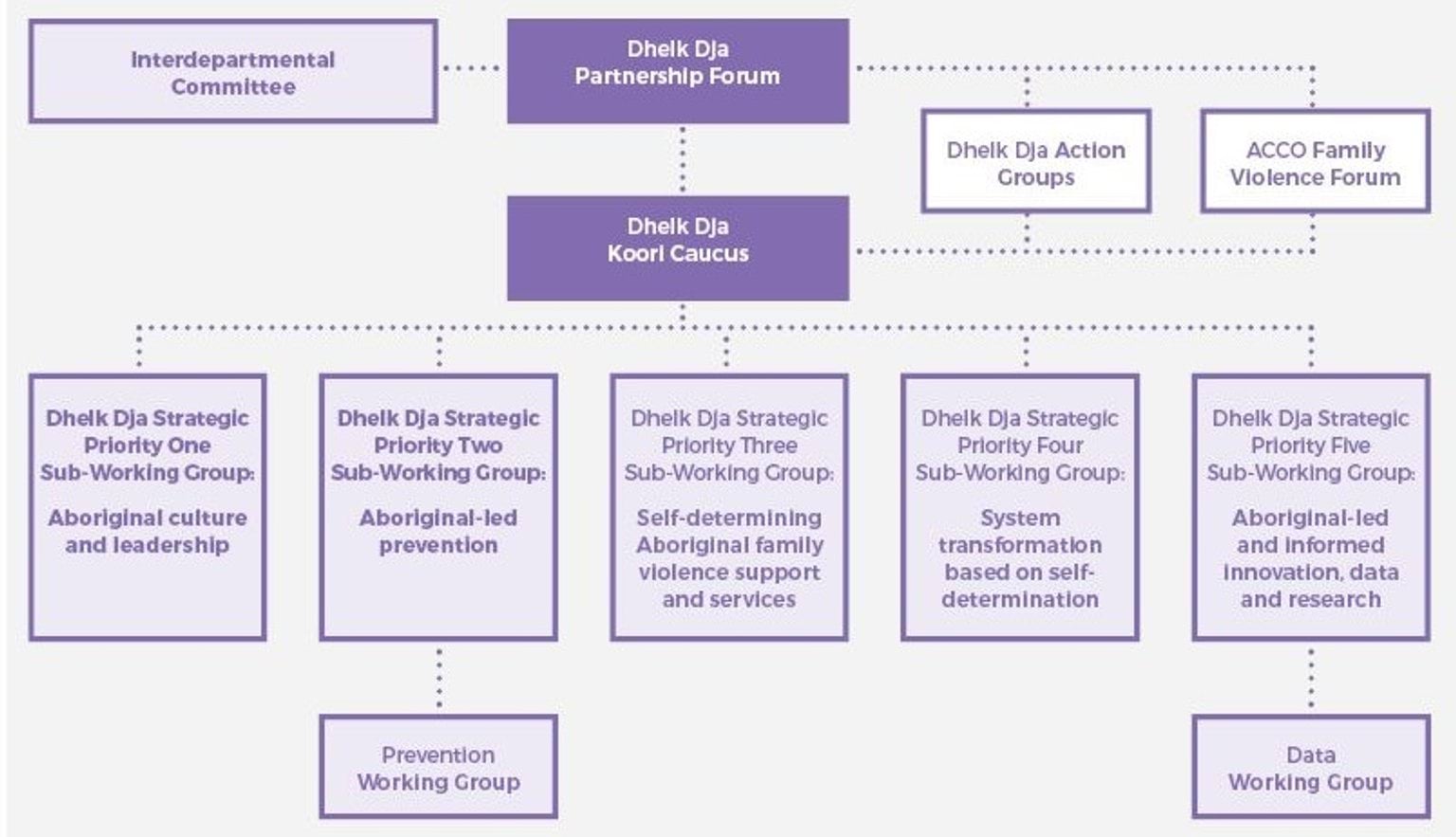

A number of governance mechanisms have been established to guide and oversee family violence prevention and early intervention effort in Aboriginal communities in Victoria, and these are outlined in Box 1. The Dhelk Dja governance structure is presented in Figure 5.

Box 1: Governance of family violence prevention and early intervention in Aboriginal communities

The Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum leads the strategic work to implement the Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families 2018-2028 agreement and subsequent rolling action plans, with the guiding principle of self-determination. Membership comprises the chairpersons of the 11 Dhelk Dja Regional Action Groups, CEOs of family violence funded ACCOs and representatives from relevant Victorian government departments.

The Dhelk Dja Strategic Priority Two Sub-Working Group: Aboriginal-led Prevention is a working group of the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum that leads and oversees the work under Strategic Priority Two of Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way. The group is co-led by a nominated member of the Koori Caucus and Family Safety Victoria’s Aboriginal Strategy Unit. The group meets quarterly, and membership is open to any member of the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum.

The ACCO Family Violence Sector Forum sits under the Dhelk Dja governance structure and is currently co-chaired by the CEO of the VACCA and the director of the Centre for Workforce Excellence Unit, Family Safety Victoria. It brings together the CEOs of all family violence funded ACCOs, Dhelk Dja regional coordinators and government representatives from Family Safety Victoria and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing to ensure all family violence services and responses for Aboriginal people are developed in a culturally safe way.

The Primary Prevention Sector Reference Group supports the government’s accountability for the broader family violence primary prevention reforms, under the 10-year Free from Violence strategy. This advisory group meets quarterly and provides strategic advice to the Victorian Government on any current and emerging issues for the implementation of the reforms. Membership comprises Victorian Government departments and non-government agencies whose core business includes primary prevention of family violence, including those that have specific expertise in Aboriginal self-determination.

The Partnership Forum on Closing the Gap Implementation is a time-limited forum, being set up to partner with the government in the decision-making process surrounding the implementation of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, consistent with Victoria’s Closing the Gap Implementation Plan. Membership will comprise an ACCO representative from each sector that covers the National Agreement targets and action areas, Aboriginal governance forum delegates and senior departmental executives from all Victorian Government departments. The forum will operate until 2023, when the implementation plan is to be reviewed.

Footnotes

- We identified four Royal Commission recommendations that relate specifically to primary prevention and early intervention within Aboriginal communities: recommendations 142, 144, 187, 189; and seven recommendations that are broader in focus but are relevant to Aboriginal prevention and early intervention: recommendations 142, 145, 146, 147, 152, 187, 189.

- Noting that the behaviour change campaign with a specific focus on preventing family violence for Aboriginal people has been postponed to the second action plan 2022–2025.

Prevention and early intervention initiatives

There is a wide range of effective prevention and early intervention initiatives being led by Victorian Aboriginal communities

In our consultations, stakeholders spoke of the longstanding nature of prevention work in Aboriginal communities, much of which predates Victoria’s substantial history of broader effort to prevent family violence and violence against women. Aboriginal stakeholders expressed some disappointment that this rich history of Aboriginal-led prevention hasn’t always been acknowledged. This is in part because of the distinct approach in Aboriginal communities (described in Box 2), which may not always be recognised as formal family violence prevention work.

Box 2: Distinct approach to family violence primary prevention and early intervention in Aboriginal communities

Aboriginal-led family violence primary prevention and early intervention efforts differ from mainstream approaches in three main respects:

Impacts of colonisation as a key driver of family violence: While mainstream prevention models target gender equality as the primary driver for family violence, Aboriginal-led responses also strongly focus on the legacy of colonisation, combined with the impact of continuing discrimination – as reflected in Our Watch’s Changing the Picture framework (see Figure 10 later). Aboriginal stakeholders spoke about some discomfort with the structured gendered analysis that underpins mainstream prevention efforts because it doesn’t sit comfortably with the Aboriginal communities’ inclusive view of family and culture, explaining that while this doesn’t mean gender is irrelevant, it is only one element as the focus is on keeping families together.

Family violence prevention as part of a holistic approach to wellbeing: ACCOs consulted for this report explained that their central focus is on cultural strengthening, connectedness and cultural identity with family and community. This holistic approach to prevention is directed at broad community health and wellbeing outcomes, where family violence is one of a number of areas addressed, and messages on family violence are not always explicit. The focus is on healing all the factors that contribute to family violence and collectively aiming to prevent it, and as a result much of the work that occurs is not formally recognised as family violence prevention. Stakeholders also described that their approach focused much more strongly on the whole of community, including men who are using violence. Providing holistic, culturally responsive, competent and safe wraparound services is a critical approach to all prevention and early intervention work undertaken by ACCOs.

Integrated approach to family violence primary prevention, early intervention and response in Aboriginal communities: Aboriginal-led prevention efforts are often integrated with early intervention, response, and recovery. One stakeholder explained that primary prevention in the Aboriginal community cannot be easily separated as it is in the mainstream model given the significant intergenerational impacts of colonisation, and the historical and ongoing experience of violence and systemic racism in the community. A whole-of-community engagement model is used to raise awareness, address drivers, identify family violence and support victim survivors while engaging with those who use violence – addressing all the factors an individual and family are experiencing. Again, the integrated approach has a strong focus on cultural healing using group and trauma work with men, women and children.

Source: Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor based on information provided through consultations

The Royal Commission recognised the strong history of Aboriginal community-led efforts to prevent and respond to family violence in Victoria. It acknowledged that one of the key outcomes identified in the mid-term evaluation of the Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families: Towards a Safer Future for Indigenous Families and Communities 10-Year Plan 2008–2018 was the reduction in stigma associated with family violence. This had been achieved through community-led education and prevention programs over the 12 years leading up to the Royal Commission. It is clear from our consultations and the examples of community initiatives that we have seen that this work has continued strongly because it is being delivered in a wide variety of settings across the state and with different groups within communities.

There are numerous examples of excellent Aboriginal community-led prevention and early intervention initiatives to address family violence – many of which have been featured elsewhere.1 In this report we highlight six specific initiatives aligned with the primary prevention strategies for Aboriginal communities identified in the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework (see Table 1). While we have presented these as examples of individual prevention strategies, we note that all the initiatives sit across multiple strategies and that the strategies themselves are mutually reinforcing.

Table 1: Aboriginal-led community initiatives aligned with the six primary prevention strategies from the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework

| Prevention strategy | Example community initiative* |

|---|---|

| Community information and education | Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service’s school education program (see Box 3) |

| Cultural strengthening | Dardi Munwurro’s ‘Aboriginal men taking responsibility and being part of the solution’ project (see Box 4) |

| Family strengthening | Victorian Aboriginal Community Service Association Limited’s Resilience Camps (see Box 5) |

| Raising community awareness | Mullum Mullum’s Ochre Program (see Box 6) |

| Responding to grief and trauma | Bendigo and District Aboriginal Co-operative’s Cultural Therapeutic Support Program (previously known as the Strong Culture, Strong Family program) (see Box 7) |

| Self-esteem and resilience building | Djirra’s Young Luv workshop (see Box 8) VACCA's Young Koorie Women's Dance Movez Project (see Box 9) |

* Funded since the Royal Commission

Box 3: Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service’s (VALS) school education program

The Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service is delivering a community education program for Aboriginal young people on developing strong and healthy relationships. The program covers topics including respecting yourself and your partner, consent and safe sex, and young people and intervention orders. To date, nine sessions have been delivered at a high school and an Aboriginal youth rehabilitation centre, with further sessions scheduled for the second half of 2022.

The workshops use a culturally informed approach to develop young people’s knowledge and understanding of healthy relationships. Yarning circles, smaller break-out groups and case studies are used to prompt a nuanced discussion, not direct young people towards ‘right answers’. Workshops have been designed as a series of three to five sessions at each location, to allow young people to grow more comfortable with the format, develop relationships with each other, and progressively build their understanding of healthy relationships. Sessions hosted in a rehabilitation centre have used informal formats, such as cooking classes, to create safe, non-intimidating spaces for young people to discuss and share their experiences of relationships. A survey of participants found that young people found the workshops a positive learning experience and felt more connected to other Aboriginal young people after the sessions.

A Blak Wattle analysis of the program has made recommendations for improving its effectiveness. These include improving engagement with the site (schools and centres) to tailor the design of sessions. A key recommendation is to find funding to increase the duration of the program – a four-to-five-week program is only just enough time for young people to develop trust in facilitators and begin to share more openly.

Source: Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service

Box 4: Dardi Munwurro’s ‘Aboriginal men taking responsibility and being part of the solution’ project

Dardi Munwurro, in partnership with the Melbourne Storm Rugby League Club, the Collingwood Football Club and ACCOs across Victoria, created an educational program delivered by Aboriginal men for Aboriginal men. The program consisted of information sessions and conversations about preventing family violence, based on the key principles of Dardi Munwurro’s healing programs: Strong Spirit and Strong Culture, Taking Responsibility and Healthy Relationships. It also formed discussions at Dardi Munwurro’s annual Victorian Aboriginal Men’s Gathering held in Melbourne as a culturally safe space for men across Australia to come together to discuss key issues affecting Aboriginal communities.

Approximately 12,000 people participated over the two years that it was funded, with the need to pivot to online delivery of the forums. It was accessible to all community members including women, children, young people, Elders and families. The program was evaluated in 2020–21 and the key outcomes included strengthened cultural connection and identity, increased awareness and understanding of issues and violence in communities, and increased awareness of local supports and services.

Source: Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping project and FSV and Dhelk Dja Action Group Presentation

Box 5: Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited’s Resilience Camps

Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited’s Resilience Camps are camps designed to strengthen family relationships and culture, encourage healthy communication and build resilience among families. Seven family resilience camps, each three days in duration, were run over 2019 and 2021 across the North-Metro, West-Metro, Ballarat and Shepparton regions.

More than 70 families participated in cultural activities such as yarning circles, arts and crafts, guest speakers, games and fun family outings. One camp was dedicated to families that had children with disability. The demand for this initiative was so high that they had to cease advertising.

An evaluation of the camps was completed in 2020–21. The evaluation showed that the project contributed to strengthened family relationships, increased understanding of resilience, leadership and communicating emotions, strengthened connection to culture, and broke down gender stereotypes. Participants also reported acquiring a wider knowledge of services and support available to them. An unexpected positive outcome was the impact of families meeting young women from the Northern Territory, and the cultural exchange this offered, by sharing different experiences of different Aboriginal nations.

Source: Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping project and FSV and Dhelk Dja Action Group Presentation

Box 6: Mullum Mullum’s Ochre Program

The Ochre Program, facilitated by the Mullum Mullum Indigenous Gathering Place (Eastern Metro), is a program of projects centred on raising community awareness of what respectful relationships are, through prevention-themed workshops and conversations. Beginning in 2019, the program provides separate sacred spaces for men and women’s business where conversations are facilitated by the appropriate cultural workers from both the Mullum staff and guest speakers. The program also enables facilitators to identify any concerning circumstances and support and refer participants using violence who are contemplating behaviour change. The Ochre Program also aims to develop free from family violence ambassadors who will uphold the messaging of respect within families and communities.

Eight to 12 men and 50–65 community members participated during the first two years it was funded. A 2021 evaluation found evidence that the project contributed to a safe space, enhanced referral pathways and partnerships and that participants had increased an understanding of respectful behaviour, relationships and factors contributing to family violence. The project was given extended funding under the Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund.

Source: Family Violence Mapping Matrix and Mullum Mullum Indigenous Gathering Place website

Box 7: Ballarat and District Aboriginal Co-operative's Cultural Therapeutic Support Program

Previously known as the Strong Culture, Strong Family program, Ballarat and District Aboriginal Co-operative’s Cultural Therapeutic Support Program was a family-based primary prevention program delivered in the Grampians region from 2018 to 2020. The program consisted of a series of events and camps facilitated for approximately 250 people, with the aim of strengthening the local Aboriginal communities’ connection to their land and traditional way of life. There were whole-of-family events, with separate events for men, women and children (men’s business, women’s business and kids’ business). 'Healthy relationships' was the key focus, along with cultural connection and pride. Elders and community members were consulted during the design phase of this trauma-informed cultural healing approach to address attitudes and behaviours, and this involvement was identified as a key advantage for the program.

Source: Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping project and FSV and Dhelk Dja Action Group Presentation

Box 8: Djirra’s Young Luv workshop

Djirra is an ACCO with more than 20 years’ experience accompanying Aboriginal women, and their children, on their individual journeys to safety and wellbeing. Djirra delivers holistic, self-determined and culturally safe specialist family violence services and early intervention and prevention programs. Djirra also amplifies the voice of Aboriginal women through its advocacy and campaigning for system-wide change.

Young Luv is a workshop for young Aboriginal women (13–18 years old) that reinforces concepts of healthy and respectful relationships within a framework of Aboriginal culture, experiences and values. The workshops are designed and facilitated by young Aboriginal women for young Aboriginal women. The workshops are place-based and are delivered across Victoria in collaboration with local ACCOs, mainstream organisations and schools. Young Luv began in 2015 and, after a series of short-term grants, secured long-term multi-year funding through the Department of Justice and Community Safety in 2017. This sustained funding has been key to enable the program to adapt and grow in scope.

The objectives of the program are to:

- provide a culturally safe space for young Aboriginal women to connect to culture and community

- raise awareness around family violence, gender-based violence and unhealthy relationships

- provide tools to identify warning signs and forms of family violence and unhealthy relationships

- create a local support network to learn from and go to for advice and help, if needed

- challenge misconceptions about Aboriginal women and family violence and to shift attitudes and beliefs

A key success factor of the program has been the design of culturally informed, inclusive and engaging content and resources that validate and celebrate cultural identity and deliver educational information in a positive, age-appropriate way. These resources include presentations, zines*, toolkits and two successful animation films that provide Aboriginal women with culturally specific messaging around healthy relationships and family violence. Recently, Young Luv has also moved into the digital space, designing and launching the Young Luv Instagram Campaign. This social media campaign responds to the need to engage a younger audience through different platforms and mediums that are responsive to the realities, needs and interests of young Aboriginal women (see illustration in Figure 9, later).

Whether in the workshops or through its online presence, a core element of Young Luv is to create a culturally safe space for young Aboriginal women to draw on culture as a protective factor and to be equipped with knowledge and tools and the confidence to challenge unhealthy behaviours and relationships.

There has been overwhelmingly positive feedback from young Aboriginal women attending Young Luv workshops. A recent review found 99 per cent of participants reported knowing more about types of violence and warning signs, 97 per cent reported understanding more about healthy and positive relationships and 99 per cent of participants felt better equipped to challenge unhealthy relationships.

*A zine is a small print-run, self-published booklet made up of newly created or appropriated texts and images.

Source: Djirra

Box 9: Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency’s Young Koorie Women’s Dance Movez Project

The Young Koorie Women’s Dance Movez Project was developed by VACCA in partnership with Indigenous Hip Hop Projects. This project was developed for young women aged 10–24 years in the Southern Metropolitan area, currently in or previously in out-of-home care, who are disengaged or at risk of disengagement from education or employment, in contact with the justice system and at risk of family violence. Indigenous Hip Hop Projects held weekly Aboriginal cultural and contemporary dance and yarning circles integrated with family violence prevention messaging, with the aim of providing the young women with knowledge and skills so they are less likely to enter violent relationships and more likely to seek help.

Around 15 young Aboriginal women participated in the project, which was given pilot funding from the Preventing the Cycle of Violence Aboriginal Fund. An informal evaluation found that the women who took part felt a strengthened cultural connection, increased knowledge of early indicators of family violence and of what makes a healthy, respectful relationship and where to get culturally safe help and supports. It also contributed to self-esteem and resilience building.

Source: Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping project and FSV and Dhelk Dja Action Group Presentation

Government efforts to support Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention

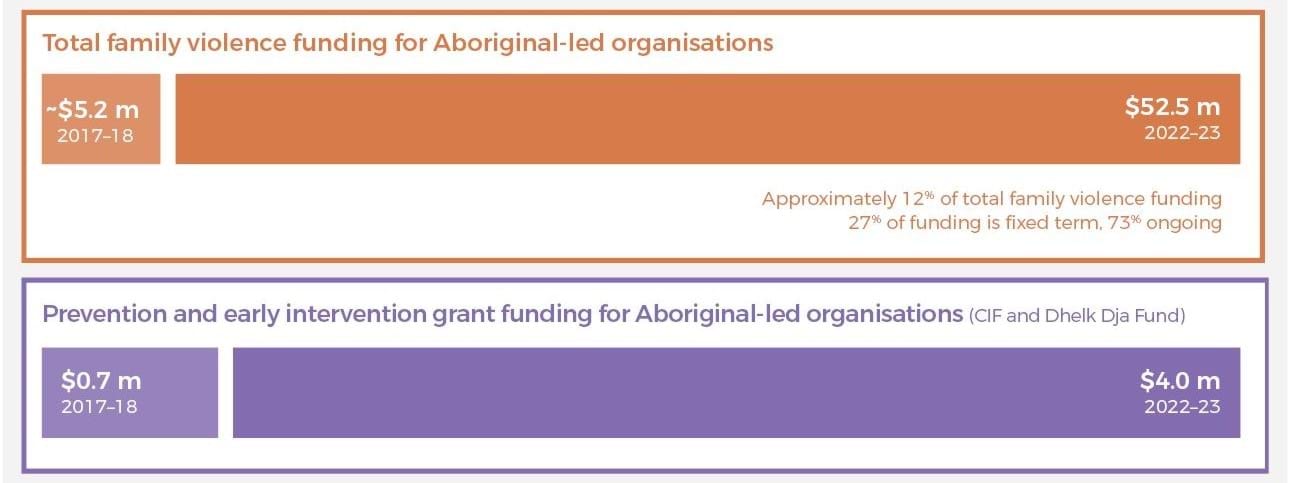

Prior to the Royal Commission, government support for family violence prevention and early intervention efforts in Aboriginal communities was provided primarily through grants under the Community Initiatives Fund (at the time of the Royal Commission grants consisted of $59,000 per year for each Indigenous Family Violence Regional Action Group) and under the Aboriginal Justice Agreement (for example, Koori Community Safety Grants). Since then, there have been concerted efforts by government to strengthen support for Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention initiatives in the family violence area, including:

- Aboriginal-led prevention as one of five priority areas under the Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families Agreement 2018–2028 and establishment of the Aboriginal-led prevention working group (Dhelk Dja Strategic Priority Two Sub-Working Group) to progress delivery of relevant initiatives in the first Dhelk Dja action plan, including consideration of prevention funding priorities.

- An increase in the Community Initiatives Fund (administered by the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing) to $100,000 per region per year, with funding allocations determined by each Dhelk Dja Action Group based on applications from local Aboriginal community groups and organisations and the priorities in their communities. For the 2022–23 funding round, the allocation was increased to $200,000.

- Creation of the Aboriginal Family Violence Primary Prevention Innovation Fund 2018–2021 (administered initially by the Department of Premier and Cabinet and transferred to the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing), which provides $3.2 million for 14 initiatives led by 13 Aboriginal organisations. Funding was provided to trial, test and evaluate new and innovative primary prevention initiatives for Aboriginal people and their communities under the Free From Violence First Action Plan.

- Creation of the Preventing the Cycle of Violence Aboriginal Fund 2018–2020 (administered by Family Safety Victoria), which provides $2.7 million over two years to 11 Aboriginal-led organisations and community groups. Funding was targeted at family violence prevention and early intervention projects that ‘aimed to build respectful, culturally rich, strong and healthy relationships for Aboriginal children, families and Elders’.

- Establishment of the Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund (administered by Family Safety Victoria in the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing), which provided a total of $18.2 million over two years (2021–22 and 2022–23) for eligible Aboriginal organisations and community groups to deliver tailored responses for victim survivors and people who use violence. This was made up of an initial allocation of $14.2 million in March 2021 to 46 projects across four streams: frontline family violence services; holistic healing; preventing the cycle of violence; and workforce capability. A further $4 million was allocated in May 2022 to 34 projects across three further priority areas identified by the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus: Aboriginal frontline family violence services; working with male victims of family violence; and preventing the cycle of violence – strengthening Aboriginal families. Across the two funding allocations, 16 prevention and early intervention projects were funded (representing 29 per cent of all projects through the fund).

- Under the Aboriginal Justice Agreement (administered by the Department of Justice and Community Safety), longer term funding has been secured for a range of prevention initiatives delivered by Djirra and Dardi Munwurro, including the Koori Women’s Place. The department has also consolidated its funding agreements with Aboriginal-led organisations so they have a single agreement covering all initiatives they are funded to deliver, with streamlined reporting requirements.

The increased funding and additional funding streams for prevention and early intervention have supported a wide range of projects across different communities, settings and cohorts, and have also enabled multi-year funding for some initiatives (two years under the Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund and three to four years under the Aboriginal Justice Agreement) more recently. There has also been a range of activity to evaluate initiatives and build evaluation capacity, which is discussed later in this report. A further recent key piece of work is mapping of Aboriginal-led prevention activities that will allow clearer analysis of the coverage and gaps in prevention programming to date.

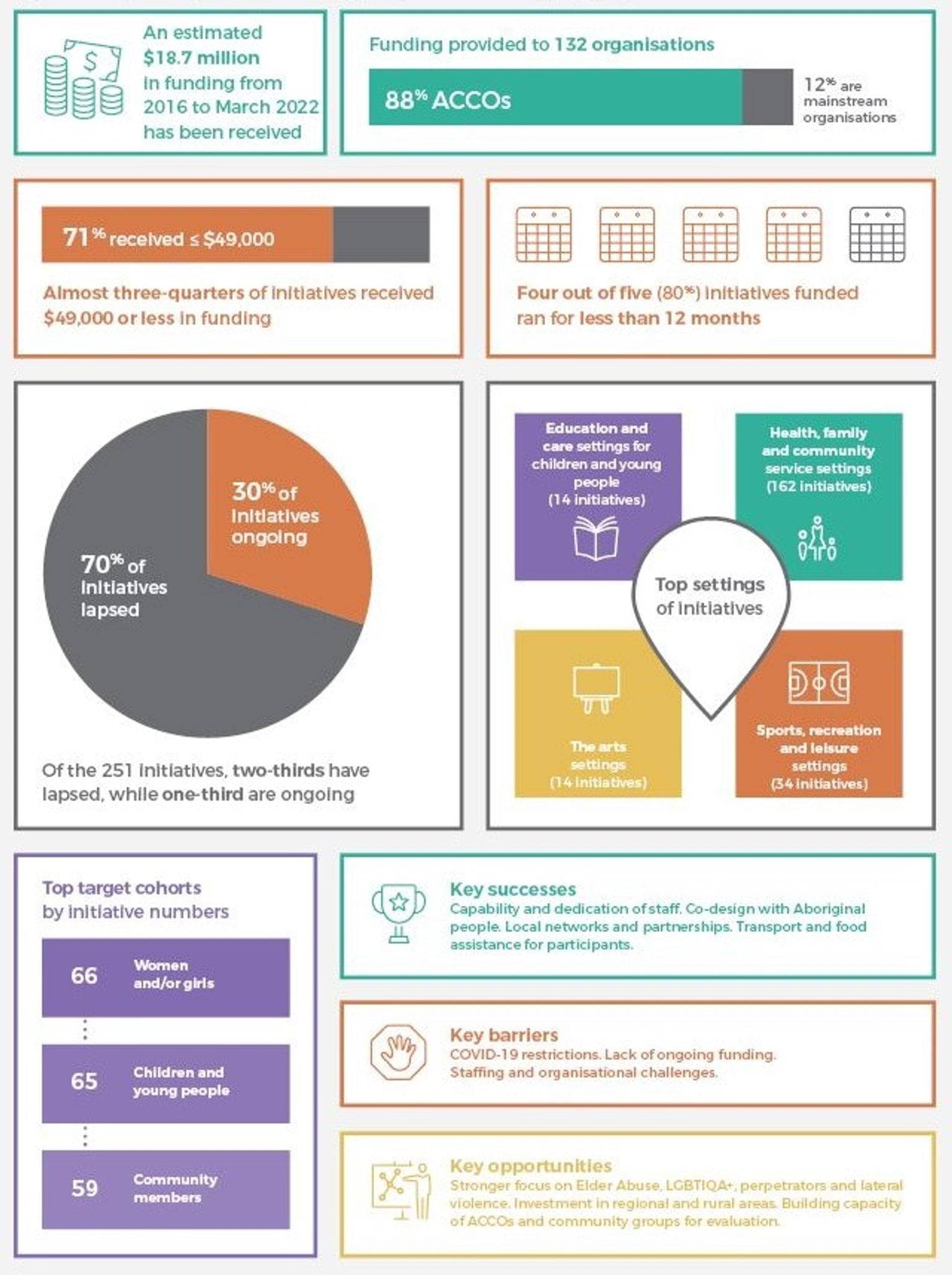

Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping Project 2021–2022

Fulfilling a commitment under Dhelk Dja Action Plan Strategic Priority Two, Respect Victoria (in partnership with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing’s Office for Family Violence and Coordination and Family Safety Victoria) commissioned a comprehensive mapping of Aboriginal-led prevention initiatives delivered from 2016 to March 2021. This work was intended to provide the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum with a strategic overview of primary and secondary prevention activity and investment, to identify gaps and opportunities for effective prevention initiatives in Aboriginal communities and to contribute to establishing a roadmap for future investment. Deliverables of the project included a mapping report and database of prevention initiatives. We understand that the database is intended to be updated over time to provide Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus with a live resource.

The prevention mapping report notes that the Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Department of Education and Training did not contribute to the project and therefore there are likely other relevant initiatives – such as the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service’s school education program outlined in Box 3 above – that are not included. To ensure a complete picture to support the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus in its strategic oversight of family violence prevention, relevant initiatives funded by other areas of government should be included in the database. Key findings from the project are captured in Figure 6.

Figure 6 also shows that more than 250 initiatives have been implemented between 2016 and 2021, with estimated funding of $18.7 million,2 the majority of which were funded under the Community Initiatives Fund (199 of the 251 initiatives). At the time of conducting the mapping in March 2022, one-third of the initiatives were still operating while two-thirds had finished.

One positive development supporting government’s commitment to self-determination is that Aboriginal prevention funding is now directed only to Aboriginal-led organisations. As the mapping report found, previous grants had been available to mainstream organisations. Between 2016 and 2022, 12 per cent of organisations funded for Aboriginal prevention projects were mainstream organisations – mostly in the earlier years.

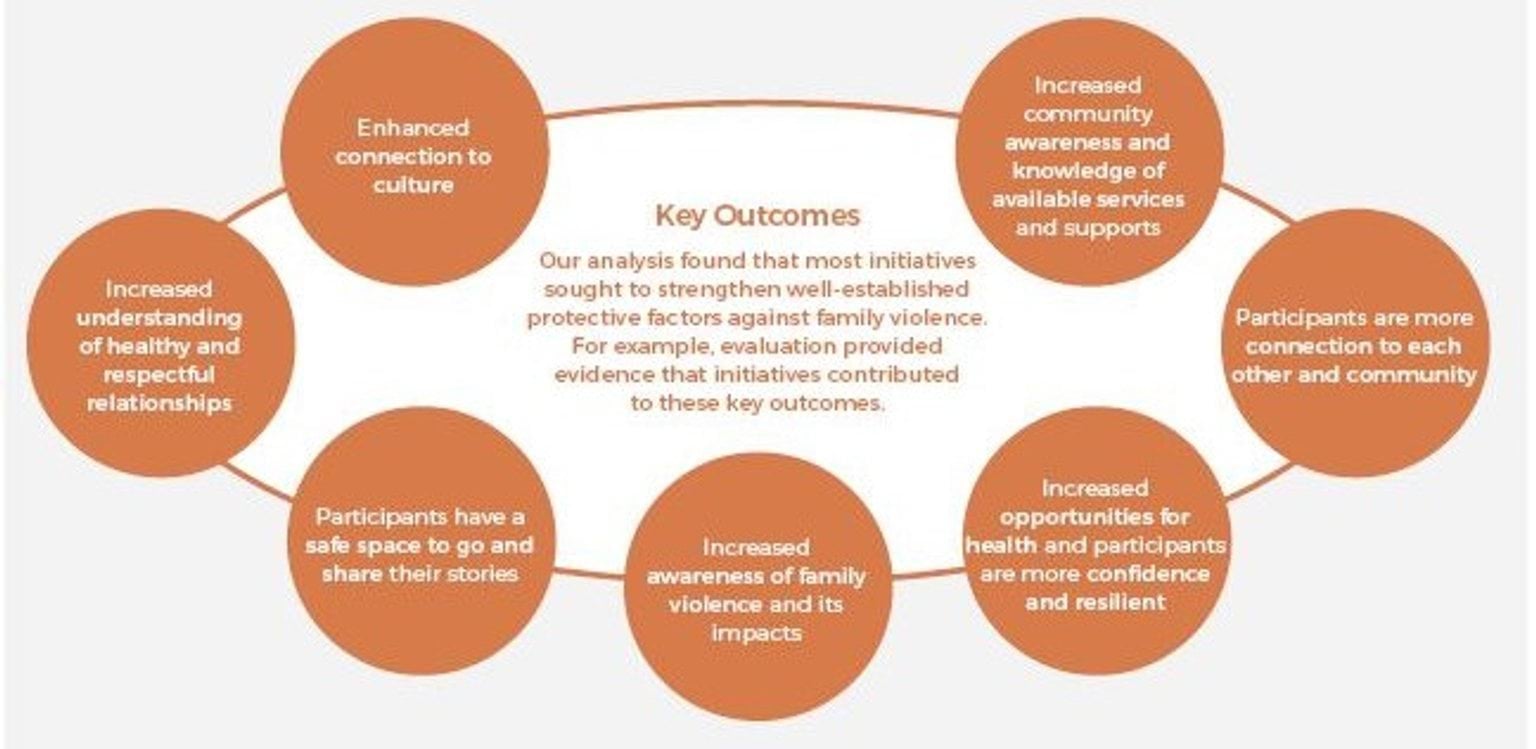

The prevention mapping project identified that 35 of the 251 initiatives (14 per cent) had conducted evaluation activities and that these evaluations provided evidence of common outcomes (see Figure 7).

This work occurred in a challenging context for the family violence prevention sector as a whole in recent years. As Respect Victoria’s 2018–2021 progress report to the Victorian Parliament notes, reports of family violence increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our stakeholder consultations revealed that this surge led to organisations shifting their focus and resources towards more urgent responses to people experiencing or at risk of family violence rather than primary prevention. Pandemic-related restrictions also limited the ability of organisations to deliver face-to-face prevention activities and to engage with communities, although the prevention mapping report identified that many organisations found innovative ways of continuing to engage with communities, including through moving to online or hybrid delivery.

The prevention mapping report also identified a number of challenges and opportunities in progressing prevention work within Aboriginal communities, including:

- inadequate funding for prevention relative to the size of the problem and a need to address short-term funding and burdensome reporting requirements

- the need for a stronger focus on some cohorts and forms of violence, in particular elder abuse, violence affecting the LGBTQI+ community, and lateral violence

- building the capacity of organisations to monitor and evaluate their projects and ensuring that data sovereignty principles are upheld

- increasing opportunities to celebrate success and achievements in Aboriginal prevention of family violence through strengths-based approaches that facilitate continuous improvement and learning.

Features of good practice

Based on our consultations and analysis provided in a range of other reports,3 several features of best practice in Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention initiatives being delivered in the community emerged. These include:

- Multi-layered outreach: Delivery of broader community programs that are pathways to more targeted, intensive programs where participants need more in-depth support. For example, Djirra runs the broadly accessible Young Luv program, which educates young women on healthy relationships (see Box 8, earlier), and women from this program with greater needs can then access more intensive services such as the Dilly Bag program and the Koori Women’s Place. Similarly, Dardi Munwurro runs its Men’s Gathering events (see Figure 8) and Brother to Brother line, which can act as a referral pathway through to their other programs, as needed.

Figure 8: Dardi Munwurro’s statewide men’s gathering event

Source: Flyer and photograph supplied by Dardi Munwurro

- Community-driven design and participation: Involving local communities, particularly Elders, in identifying needs, and designing and implementing activities is critical to their success. For example, in the evaluation of the Aboriginal Family Violence Primary Prevention Innovation Fund, program implementation staff identified the involvement of Elders as a key success factor for activities. One stated:

They have times where they [Elders] really lead the camp, the cultural activities, and the conversations with young people … For me, as someone who's not Indigenous, I'm able to step out and go this actually isn't a conversation for me – Aunty, can you step in and have this conversation? And they're really available to be able to be there for the young people and what they need, and facilitate the cultural activities as well.

Another stakeholder noted that involving Elders enormously strengthens their work, with Elders acting as ‘navigators’ for young men, and also helps with modelling respect for Elders within the community.

Other programs focused on using female Elders to guide women’s groups, such as the Deep Healing through Cultural Strengthening – Women's Project implemented by Oonah Health & Community Services Aboriginal Corporation. The project brought together female Aboriginal victim survivors to journey through a process of deep healing with the support of Aboriginal Elders and a professional counsellor experienced in working with Aboriginal communities.

- On-Country program delivery: Activities such as resilience camps and cultural bush walks provide an opportunity to focus on positive change by taking participants out of their regular environment and on to Country to enhance building a strong connection with culture and community. Examples include Winda-Mara Aboriginal Corporation’s Tracks to Stronger Communities project, which aimed to nurture identity by engaging youth to walk on Country alongside Elders and other community members, and VACCA’s Safe and Strong project, which delivered cultural camps to Aboriginal teenagers living in out-of-home care to support their connection to culture and ability to recognise signs of unhealthy relationships.

- Attendance support: Providing transport and food assistance to participants and other culturally relevant incentives (for example, tickets to attend a Melbourne Storm game as part of Dardi Munwurro’s statewide men’s gathering – see Figure 8 above) helps to enable attendance at family violence prevention events.

- Engaging and relevant messaging: Using culturally relevant messaging for family violence prevention initiatives (for example, ‘Men’s Gathering’ in Figure 8 above and ‘drop in if you need a safe yarn’ in Figure 9 below), with a particular focus on ‘cultural strengthening’ rather than ‘preventing family violence’ can send a positive and inviting message to potential participants. Projects also used modes of messaging that resonated with the audience and popular channels to reach audiences – for example, Djirra’s social media campaigns, which appeal to young people. Other projects harnessed Aboriginal community radio listeners in combination with social media, such as 3KnD Kool ‘N’ Deadly’s Standing Strong Together project, which worked with a team of Aboriginal community members to deliver a one-hour weekly radio and online program with the goal of supporting, educating, informing and changing community attitudes towards family violence.

Figure 9: Djirra’s family violence social media campaigns appealing to younger audiences

Source: Djirra Victoria Instagram accounts @djirravic and @djirra.youngluv

Work undertaken through the Dhelk Dja and Aboriginal Justice agreements has contributed to a more strategic approach to government investment in community-led prevention and early intervention initiatives since the Royal Commission, and supported a wide array of initiatives across different settings. However, a range of issues and challenges facing organisations leading this work in their communities were raised with us during our consultations. These are consistent with themes identified in the prevention mapping report, and a number of past reports including the Royal Commission’s report.

We find that there are a number of areas for further development to better support and position Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention work to achieve the aims of the Dhelk Dja Agreement and the family violence reductions committed to in the Victorian Closing the Gap Implementation Plan (2021–23). These areas are outlined in the remainder of this report.

Footnotes

- For example: Royal Commission into Family Violence report; Our Watch’s Changing the Picture framework; Respect Victoria’s 3-Year Prevention Progress Report to Parliament; the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework; and Karabena Publishing (2021): Evaluation of the Aboriginal Family Violence Primary Prevention Innovation Fund, 2018–2021 (commissioned by DFFH).

- The first round of Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund initiatives and funding are included in the figures presented in Urbis (2022): Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping Project (prepared for Dhelk Dja Strategic Priority Two Sub-Working Group through Family Safety Victoria) but not the most recent round from May 2022.

- For example: Urbis (2022): Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping Project (prepared for Respect Victoria) and Karabena Publishing (2021): Evaluation of the Aboriginal Family Violence Primary Prevention Innovation Fund, 2018–2021 (commissioned by DFFH).

Frameworks and evaluations

There is a need for a more sustained approach to support Aboriginal organisations to apply frameworks and evaluate the outcomes of initiatives

Frameworks guiding family violence prevention and early intervention effort in Aboriginal communities

Organisations we consulted spoke about using a variety of frameworks to guide their work. These included Our Watch’s Changing the Picture (see Figure 10), the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework (see Figure 11) and the Nargneit Birrang – Aboriginal Holistic Healing Framework for Family Violence. However, some stakeholders commented that these frameworks lack supporting resources and that organisations are left to work out how to apply them in practice. Certainly, Changing the Picture does not have the same practice tools and resources that accompany Change the Story.

Similarly, the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework, while providing a high-level overview of the key considerations and approaches to guide primary prevention effort, does not outline the comprehensive suite of actions needed to address family violence in Aboriginal communities. It also predates the development of Changing the Picture and would benefit from greater alignment with the national framework and subsequent Victorian mainstream prevention frameworks such as the Free From Violence strategy.

A refresh of the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework is a key commitment under the first action plan of the Dhelk Dja Agreement (see also Table 2 in section 5 of this report). We agree that enhancing the strategic approach to family violence prevention in Aboriginal communities would be supported through an updated Aboriginal primary prevention framework. This will ensure there is a shared understanding across government, Aboriginal-led organisations and communities about what primary prevention is in the Aboriginal context, where the priorities are, and how this work intersects with or sits alongside mainstream prevention effort.

While Dhelk Dja has a Monitoring, Evaluation and Accountability Plan that includes a high-level theory of change across the agreement’s five strategic priorities and associated actions, it does not provide a detailed articulation of the different types of prevention activity needed to achieve the strategy’s intended outcomes. Without outlining how outputs and activities feed into the desired outcomes, it is not user-friendly for small community organisations looking to define their program logic and how they fit into the state-level framework for preventing family violence.