- Date:

- 22 Feb 2022

This is the second of seven topic-based reports, as outlined in the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor's plan for 2021–2022.

This report examines the Victorian Government's recently implemented whole-of-family-violence-reform governance changes, and the extent to which these changes are supporting effective oversight and integration of cross-government reform effort.

Monitoring Victoria's Family Violence Reforms: Reform Governance

Foreword

Jan Shuard PSM

Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

This is the second of our topic-based reports and examines the newly established governance arrangements across the whole reform program and within government departments. The arrangements are still being refined in the context of recent machinery-of-government changes. With this embedding of new structures and the ongoing disruption of the pandemic, it is a credit to the leadership in government and the sector, and a demonstration of the ongoing commitment to the reforms, that these changes have progressed.

Strong governance is as critical now as it was in the beginning, building on the foundations that have shaped oversight and coordination. Our review found that the new cross-government arrangements are well structured and inclusive. As it is early days, there are improvements in reporting that would be helpful, and we make several suggestions in this report, some of which come from active participants in the oversight arrangements.

It is pleasing to hear of strong support among sector stakeholders for the new Family Violence Reform Advisory Group approach. It is a maturing relationship with government and a collaborative forum where members are genuinely heard and able to influence the agenda. The report also highlights good examples of collaborative governance and service design. This should be further developed to harness the expertise of those with lived experience and practice knowledge. These partnerships are especially needed for children and young people who are determined to be recognised as victim survivors in their own right and who have the expertise to shape the services they need.

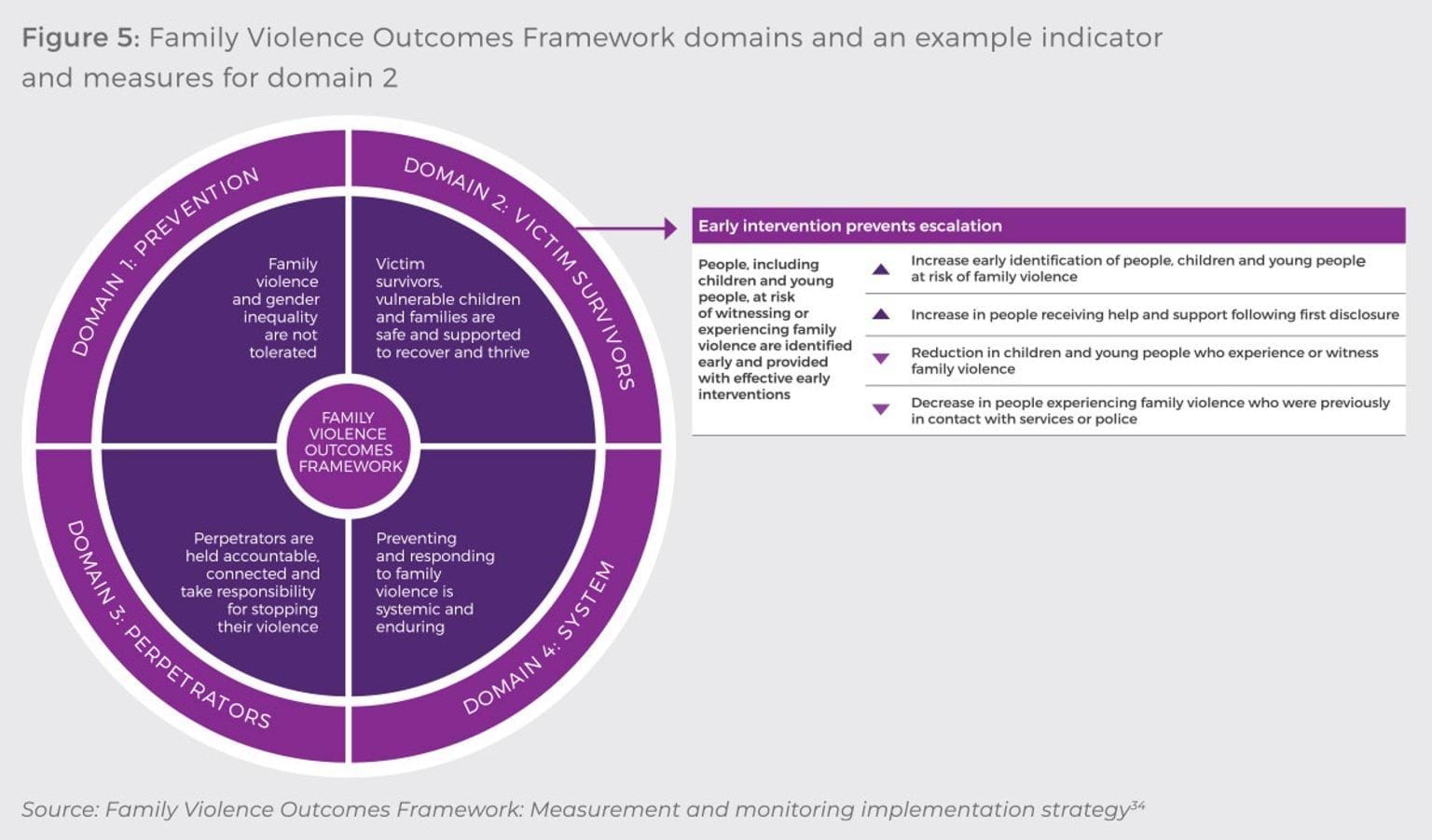

Given we are at the halfway point of the reform program and beyond simply implementing recommendations, those tasked with governance arrangements need an understanding of the overall impacts of the reforms – in particular, the progress, barriers and risks to achieving the outcomes articulated in the Family Violence Reform Outcomes Framework and rolling action plans.

It is challenging work, but there remains a key gap in the reporting framework and therefore the ability for those charged with governance to monitor and report on progress. There is no clear relationship between the major investments and their intended or projected bearing on high-level outcomes. While activities have been grouped under what they are expected to contribute to, there has been no articulation of the connection between the inputs (delivery of initiatives), the outputs (provision of services) and the results or outcomes these are having. It is not possible to determine the extent to which outputs are contributing to outcomes. Without this logic, governance mechanisms are limited in their ability to measure, monitor and report on progress. Oversight bodies should now be pivoting their efforts towards measuring short and medium-term outcomes – what is working and what is not – to determine progress towards achieving the vision.

There are many positive features of the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum. These are best summarised in the words of stakeholders who described the forum as an excellent model of community-led governance that could be adopted in other areas to deliver improved outcomes for communities.

Lastly, I wish to thank all of those who contributed to this report. Without their assistance and collaboration, we could not do justice to this work. I particularly want to acknowledge the role of implementation agencies, the sector, the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and specifically the young lived experience consultants from Berry Street’s Y-Change program, in providing valuable and constructive input and feedback.

Jan Shuard PSM

Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

Monitoring context

About the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor (the Monitor) was formally established in 2017 as an independent statutory officer of the Parliament after the Royal Commission into Family Violence released its report in 2016.

The role is responsible for monitoring and reviewing how the Victorian Government and its agencies deliver the family violence reforms as outlined in the government’s 10-year implementation plan Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan for Change.

On 1 August 2019, former Victorian Corrections Commissioner Jan Shuard PSM was appointed as the Monitor under section 7 of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor Act 2016. Jan took up her role on 2 October 2019, replacing Tim Cartwright APM, the inaugural Monitor.

Monitoring approach

The Monitor’s 2021–2022 plan was developed through a process of consultation with government and sector stakeholders. Topics were selected that aligned areas of greatest interest and concern to sector stakeholders, with reform implementation activity outlined in the government’s second Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023. In determining topics, the focus was on areas where an independent perspective could add the most value to the ongoing reform effort.

Topics selected for monitoring throughout 2021 and 2022 are:

- accurate identification of the predominant aggressor

- family violence reform governance

- early identification of family violence within universal services

- primary prevention system architecture

- Aboriginal-led primary prevention and early intervention

- crisis response to recovery model for victim survivors

- service response for perpetrators and people using violence within the family.

In undertaking our monitoring, the following cross-cutting themes are examined across all topics:

- intersectionality

- children and young people

- Aboriginal self-determination

- priority communities such as LGBTIQ+, people with disabilities, rural and regional, criminalised women, older people and refugee and migrant communities

- data, evaluation, outcomes and research

- service integration.

Monitoring of the selected topics is based on information gathered through:

- consultations with government agency staff

- consultations with community organisations and victim survivor groups

- site visits to service delivery organisations (where possible within coronavirus (COVID-19) restrictions)

- attendance at key governance and working group meetings

- documentation from implementation agencies, including meeting papers and records of decisions by governance bodies

- submissions made to the Monitor in 2020 by individuals and organisations (many of these are available in full on the Monitor’s website).

Engaging victim survivors in our monitoring

We are also actively seeking to include user experience and the voices of victim survivors in our monitoring. The office is working with established groups including the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, Berry Street’s Y-Change Lived Experience Consultants, and the WEAVERs victim survivor group convened by the University of Melbourne.

Stakeholder consultation

The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor would like to thank the following stakeholders for their time in monitoring this topic:

- Aboriginal Community Elders Services

- Berry Street Y-Change Lived Experience Consultants

- Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare

- Children’s Court of Victoria

- Department of Education and Training

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

- Department of Health

- Department of Justice and Community Safety

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus

- Eastern Metropolitan Family Violence Partnership

- Federation of Community Legal Centres

- Gippsland Family Violence Alliance

- Inspector General for Emergency Management

- inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence

- Magistrates’ Court of Victoria

- No to Violence

- Respect Victoria

- Safe and Equal (formerly Domestic Violence Victoria and Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria)

- Seniors Rights Victoria

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria

- Statewide Family Violence Integration Advisory Committee

- Switchboard Victoria – Rainbow Door

- Women’s Legal Service Victoria

- Women with Disabilities Victoria

- Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council

- Victoria Legal Aid

- Victoria Police

- Victorian Auditor General

- Victorian Council of Social Services.

Introduction

Strong governance arrangements help to support the effective implementation of any initiative. In complex whole-of-government and community sector reforms, such as Victoria’s family violence reforms, they are both challenging to get right and particularly critical for success.

In this report we examine the recently implemented whole-of-family-violence-reform governance changes and the extent to which they are supporting effective oversight and integration of cross-government reform effort. This includes consideration of:

- the inclusion of victim survivor voices within reform governance

- the operation of governance structures to support Aboriginal self-determination.

We also examine governance arrangements within government departments and agencies to oversee implementation of the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM), as one of the more significant initiatives in the reform.

In undertaking this examination, we acknowledge that many of the revised structures and processes are still being refined and embedded, and that this work is occurring in an environment of ongoing service demand pressure and diversion of resources to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic response. In this context, the findings outlined in this report are intended to assist Victorian Government departments and agencies as they continue their efforts to refine and strengthen governance of family violence reform delivery during 2022 and beyond.

Key findings and proposed actions

A comprehensive set of governance structures were established to oversee delivery of Victoria’s family violence reform program in the years following the Royal Commission. During 2021, changes to key whole‑of‑reform governance structures were made to better integrate elements of existing governance and clarify roles and responsibilities.

We believe that the new whole-of-reform governance architecture is strong, inclusive and properly structured. Acknowledging that the revised governance systems are still newly established, our suggestions go to further enhancing the current processes to get the best out of the arrangements and the committed people who give their time to governance of the family violence reform.

While the governance foundations are strong, we find there is a need to focus on robust outcome measurement and reporting to provide government, and the community, with confidence that the substantial investment and effort are delivering the intended benefits.

The report provides our detailed analysis and findings that directly relate to the suggested actions outlined in Figure 1. These actions are also highlighted throughout the report.

Figure 1: Fifteen proposed actions for family violence reform governance

Operation of the Family Violence Reform Advisory Group and Working Groups

- Ensure meeting papers are distributed with sufficient time for members to consult their networks and sectors.

- Provide regular whole-of-reform reporting on implementation progress and planned delivery in meeting papers.

- Identify reform work that could be sector-led to better utilise the skills and expertise of members.

- Further consider how best to ensure a dedicated focus on the needs of diverse communities within the reform program.

Operation of the Family Violence Reform Board

- Establish a reform-wide risk and issues management process, including a framework for the referral of risks and issues to the Reform Advisory Group, and for escalation to the Victorian Secretaries Board.

- Ensure consistent attendance by nominated members at meetings

Governance of Primary Prevention

- Further consider governance of primary prevention within government across the interconnected areas of family violence, violence against women, sexual harm and elder abuse.

Victim Survivor Inclusion

- Provide the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council with the opportunity to determine areas for their involvement within the reform program.

- Develop additional mechanisms to bring a wider range of victim survivor voices – especially children and young people – into the implementation and oversight of the reform effort across government and increase the use of collaborative partnerships with victim survivors in progressing reform implementation.

Aboriginal Self-Determination

- Through the 10-year Aboriginal family violence investment strategy, and with the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus, consider how the Aboriginal community can be given greater decision-making authority in the distribution of funding allocated by government and capacity for longer funding arrangements.

Outcomes Reporting and Accountability

- Better articulate how initiatives and activities contribute to achieving the overarching reform outcomes and strengthen measurement of short and medium-term outcomes.

- Allocate accountability within government (either individual or shared) for outcomes to be achieved.

Governance within Individual Departments and Agencies

- Ensure relevant governance bodies receive structured reporting on implementation progress, risks and issues to support their oversight role.

- Embed outcomes monitoring in internal governance reporting arrangements.

- Ensure feedback is provided about the outcomes of victim survivor involvement when consulting the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and other victim survivor groups on reform initiatives.

What did the Royal Commission say and what has changed since?

The Royal Commission into Family Violence found that despite a growing focus on family violence and the establishment of structures to ensure coordination and integration, there remained a lack of accountability, collective ownership and oversight for the family violence system. Governance was identified by the Royal Commission as a key system limitation:

'The Victorian Government does not have a dedicated governance mechanism in place to coordinate the system’s efforts to prevent and respond to family violence or to enable an assessment of the efficacy of current efforts.'1

The Royal Commission made 10 recommendations relating to sustainable and certain governance (recommendations 193 to 202) that set out a range of structures and functions to be put in place to implement the Commission’s recommendations and oversee systemic improvements in the family violence system.

In particular, recommendation 193 required the Victorian Government to establish a governance structure consisting of:

- a bipartisan standing parliamentary committee on family violence

- a Cabinet standing sub-committee chaired by the Premier of Victoria

- a family violence unit located in the Department of Premier and Cabinet

- a Statewide Family Violence Advisory Committee

- Family Violence Regional Integration Committees, supported by Regional Integration Coordinators

- an independent Family Violence Agency established by statute.

Early reform-wide governance arrangements

Following the Royal Commission, the Victorian Government progressively established or strengthened a range of governance bodies to inform and oversee implementation of the reform program. These included:

- a coordinating unit within the Department of Premier and Cabinet, established in 2017 to lead coordination and reporting for the Victorian Government’s response to the 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission’s report, and to provide advice to the Premier, the Cabinet sub-committee and the family violence sub-committee of the Victorian Secretaries Board2

- an interdepartmental committee, established in February 2018 to provide whole-of-reform governance with responsibility for making decisions and managing interdependencies, sequencing, and risks, and escalating matters to the Victorian Secretaries Board sub-committee3

- creation of Family Safety Victoria (as an administrative office of the then Department of Health and Human Services rather than by statute) in July 2017 to lead the delivery of many of the government’s key family violence reform initiatives, including the 17 The Orange Door sites across Victoria, MARAM, Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and Central Information Point.4 Family Safety Victoria is also responsible for establishing the Centre for Workforce Excellence and leading the Family Violence Industry Plan to build workforce capacity and capability in partnership with the sector5

- a family violence sub-committee of the Victorian Secretaries Board

- a Family Violence Steering Committee consisting of senior government and sector representatives tasked with monitoring the development of a comprehensive, coordinated family violence reform agenda; providing final advice on the Statewide Family Violence Action Plan (10-year plan) and the whole‑of‑government implementation of the Royal Commission’s recommendations to the Victorian Secretaries Board Sub-committee on Family Violence, the Social Services Taskforce and by relevant Ministers for final decision making and approval6

- an Industry Taskforce to provide advice on family violence sector readiness and workforce reform

- a Ministerial Taskforce for the Prevention of Family Violence

- a Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council to provide an ongoing voice for victim survivors on how the family violence system and services should be designed and to provide advice on how family violence reforms will affect those people who use services

- greater autonomy of the Aboriginal partnership forum to oversee, coordinate and monitor implementation of the Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families agreement between the Victorian Government and Victoria’s Aboriginal community7

- strengthening the operation of the existing family violence Regional Integration Committees (representing regional family violence services and other key local sector organisations intersecting with family violence) through the addition of regional coordinating positions (called Principal Strategic Advisors)

- allocation of the Legal and Social Issues Standing Committees of the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council to serve as the bipartisan committees for family violence matters.

Much of the work to address the governance recommendations was undertaken during 2017 and 2018, and all 10 governance recommendations were formally implemented by June 2021.

Individual government departments and agencies also established their own internal governance mechanisms to oversee implementation of allocated recommendations and their contribution to the whole-of-government family violence work.

Revised governance arrangements implemented throughout 2021

A series of changes to family violence reform governance arrangements have been progressively implemented throughout 2021. In communication with sector stakeholders about the intent of the changes, Family Safety Victoria noted that they were designed to: improve the integration and embedding of regional family violence governance, Aboriginal and diverse communities, and lived and client experience representation; provide greater clarity of purpose and scope for the advisory committees; streamline and consolidate the number of former family violence reform advisory groups; and reduce the duplication of membership across content-specific governance groups. The changes to the statewide governance structures include the following:

- Creation of a new Family Violence Reform Advisory Group, which replaces and consolidates the previous Family Violence Steering Committee, Industry Taskforce, and Ministerial Taskforce for Prevention. The advisory group is responsible for providing expert advice to government on system-level impacts of the family violence reform and making recommendations to achieve an improved whole-of-system approach to prevention and response.8 The group is supported by a series of working groups progressing priority areas aligned with the Ending Family Violence: Victoria‘s Plan for Change – Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023. The advisory group met for the first time in February 2021, is co-chaired by the CEO of Safe and Equal, and the Deputy Secretary and CEO of Family Safety Victoria, and has representation from key sector organisations including:

- peak bodies for specialist family violence services that provide support to victim survivors; services that work with men who use family violence; child and family services; Victoria’s social and community sector; and sexual assault and harmful sexual behaviour services

- organisations with expertise in service delivery, workforce, housing, legal, prevention, and inclusion and equity

- key stakeholder groups: Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum, the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and Family Violence Regional Integration Committees

- government family violence reform implementation departments and agencies.

- Consolidation of four internal-to-government project-specific steering committees into a Family Violence Reform Board, which (from February 2022) has responsibility for leading whole-of-reform, cross‑government engagement and strategic oversight. It takes over this function from the Family Violence Reform Interdepartmental Committee, which becomes a policy steering committee reporting to the reform board. The reform board is co-chaired by the Deputy Secretary and CEO of Family Safety Victoria, and the Deputy Secretary of Fairer Victoria, and is supported by three project-specific working groups.

- Disbanding of the family violence sub-committee of the Victorian Secretaries Board, with family violence matters now to be considered by the full Victorian Secretaries Board.

The previously established Regional Integration Committees (which have now formed a statewide advisory committee), Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum and Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council continue to operate as before.

Machinery-of-government changes that saw the former Department of Health and Human Services replaced by a Department of Health and a new Department of Families, Fairness and Housing took effect on 1 February 2021. As part of these changes, responsibility for family violence coordination, gender equality and primary prevention moved from the Department of Premier and Cabinet to the new Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. Family Safety Victoria has also subsequently become a division within the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, rather than a separate administrative office.

The Minister for Prevention of Family Violence continues to be the whole-of-Victorian lead for key family violence reforms such as MARAM, the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and the Industry Plan.

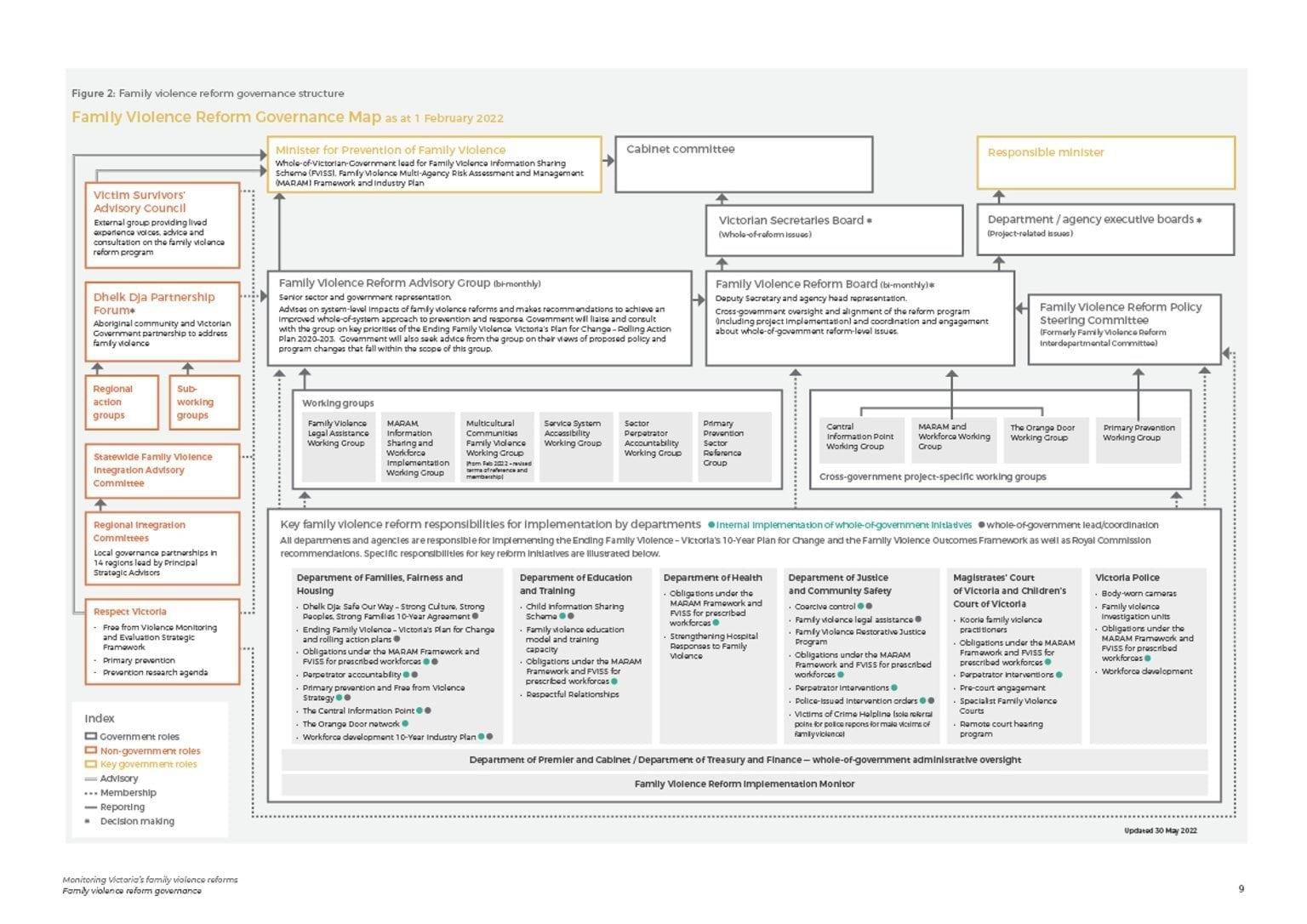

The revised family violence reform governance structure in operation (as at 1 February 2022) is presented in Figure 2.

Endnotes

1 State of Victoria (2016): Royal Commission into Family Violence: Summary and Recommendations, Parl Paper No 132, p. 6. Available at parliament.vic.gov.au/file_uploads/1a_RFV_112ppA4_SummaryRecommendations.WEB_DXQyLhqv.pdf (accessed 15 December 2021).

2 Victorian Government (2021): Establish a Governance Structure for Implementing the Commission’s Recommendations. Available at vic.gov.au/family-violence-recommendations/establish-governance-structure-implementing-commissions (accessed 3 December 2021).

3 Family Violence Reform Interdepartmental Committee, Terms of Reference (February 2021).

4 For more information, see vic.gov.au/family-safety-victoria

5 For more information, see dhhs.vic.gov.au/family-safety-victoria

6 Family Violence Steering Committee, Terms of Reference (March 2018).

7 Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum, Draft Terms of Reference (October 2018).

8 Family Violence Reform Advisory Group, Terms of Reference (April 2021).

Whole-of-reform governance arrangements

Sector stakeholders have consistently reported that the move to the new Family Violence Reform Advisory Group has been a positive development. While there was an acknowledgement of the intent to be inclusive in the early stages of the reform, the former Steering Committee and Industry Taskforce were described by stakeholders as ‘unwieldy’ and operating in a way that did not facilitate collaborative engagement or strategic risk management. In contrast, the new advisory group reflects a maturing relationship between government and the sector, providing a respectful forum for genuine engagement where members feel heard and able to contribute to, and influence, reform activity. There was praise for the co‑chairing arrangements, and although stakeholders acknowledged that quarterly meetings are not frequent enough, sector representatives felt there had been good opportunity to contribute to work out-of-session, with two out-of-session meetings in 2021. In 2022, five regular Family Violence Reform Advisory Group meetings have been scheduled.

Clear terms of reference, and renaming the sector-involved group as an advisory group, better reflects its role in providing expert advice to support government in its responsibility for leading implementation of the reform. Having representation on the advisory group from Dhelk Dja, the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and the Statewide Family Violence Integration Advisory Committee strengthens coordination and visibility between these groups and the broader reform effort. There has been consistent attendance by sector members at the meetings during 2021, and this commitment needs to be matched by some government department members, where attendance of the nominated representative has been less consistent. While delegates are usually in attendance, and it is no criticism of their participation, it does create discontinuity. Although the endorsed terms of reference for the advisory group provide for distribution of papers one week prior to meetings, several representatives told us that they would like to have meeting papers further in advance of the meetings, to provide them with sufficient time for consultation within their organisations and networks. Although there is the issue with timely distribution of papers, the advisory group papers are comprehensive and informative so that meetings are focussed and productive. Overall, the engagement and energy of the members is impressive.

In reviewing papers and observing meetings of the primary prevention, perpetrator accountability, MARAM information sharing and workforce, and multicultural sector working groups, there was good attendance and engagement at the meetings, a focus on upcoming activity and a willingness to address issues or provide further information in response to queries outside of meetings. In particular, the primary prevention sector working group provided a strong platform for collaboration to prepare the Victorian delegation for the National Women’s Summit held in September 2021. The integration of sexual assault in a meaningful way within the reform work program has also been welcomed.

While largely positive, our consultations have identified some opportunities to better support sector representatives to effectively fulfill their roles and contribute their expertise within the whole-of-reform governance arrangements. These include the following:

- Ensure advisory and working group meeting papers are provided with enough time to allow members to consult and consider the issues. This is particularly critical for members who represent wider groups (such as the Victorian Council of Social Services, Statewide Family Violence Integration Advisory Committee and the Regional Integration Committees, Dhelk Dja, Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and legal sector representatives) and who need to consult with their sectors/members to bring an informed position to the meetings [relates to action 1]. Members see this as their clear responsibility and want to be able to do this effectively.

- Improve the coordination between the different working groups that report into the advisory group. Noting that these working groups are still establishing their work plans and reporting mechanisms, and there is some crossover in representation, there is currently limited visibility among some members of the broader work program and the intersections with their areas of focus. Communicating the forward priorities and deliverables – both of the advisory group and broader reform effort – across working groups will ensure their work is informed by, and able to feed into, the whole-of-reform agenda [relates to action 2].

- There is an opportunity to make greater use of sector expertise to drive the development and implementation aspects of the reform work. Several stakeholders commented on the continuing preference for government ’in-house’ work when there is sector capacity and commitment for developing practical and user-centred solutions with government [relates to action 3]. An excellent example of this approach, and the benefits it delivered for financial assistance provided to victim survivors, is provided below in Box 1. The development of a service design model to integrate legal assistance within The Orange Door is an example where sector-led development is underway, with the model being developed jointly by government and the legal sector.

- Sector representative visibility of the whole-of-reform effort was also identified as an area needing further consideration and is discussed in more detail below.

There are some good examples of collaborative governance being employed by departments and agencies in their implementation

There are several good examples of collaborative governance and engagement in the work being led by departments and agencies (see detailed examples provided in Box 1 and Box 2). These ways of working have real benefits for the initiatives being delivered through effectively drawing on the expertise that exists outside government and fostering a sense of shared ownership and accountability between government and the sector. These examples provide a model of engagement that could be utilised more consistently in future implementation across all levels of the reform.

Box 1: Implementation of recommendation 107 – training Victoria’s financial counselling workforce

Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence recognised the crucial role of financial counsellors supporting the safety and financial wellbeing of people experiencing economic abuse, the financial impacts of family violence, and family violence–related debt.

In 2017, Women’s Legal Service Victoria and WIRE Women’s Information were jointly commissioned by Consumer Affairs Victoria to develop and deliver a training program for Victoria’s financial counselling workforce. The program provides financial counsellors with skills and knowledge to recognise economic abuse and all forms of family violence, and support clients to achieve safety and financial recovery and wellbeing.

At its inception, foundation-level training was expected to be delivered to 80 financial counsellors across Victoria and advanced training for 20 senior financial counsellors on legal and technical skills for complex family violence casework, including economic abuse. The training program drew extensively on the expertise of Women’s Legal and WIRE Women’s Information, as well as collaboration with Financial Counselling Victoria, financial counsellors working in a range of settings, and many specialists and subject matter experts.

Vastly exceeding expectations, as at December 2021, close to 300 financial counsellors across Victoria have completed the foundational training program, with 642 attendances across the various modules. The original program of foundational and advanced training was augmented with a masterclass and a leaders’ class. These developed into a community of practice collaborative learning format that supports senior and leading financial counsellors to resolve emerging practice-based challenges relating to the complex intersections of family violence, credit law and family law. Importantly, the program contributed to Victoria’s financial counselling workforce, further developing the knowledge and confidence to advocate for industry and system reform to remove barriers to the safety and financial wellbeing of people affected by family violence. Victorian financial counsellors now play an educative role to the finance, credit and utilities industries on the impacts of family violence and are leading the way across Australia.

The governance approach of Consumer Affairs Victoria empowered Women’s Legal and WIRE Women’s Information to drive the project and was a key determining factor in the program’s success. The approach facilitated ways of working that led to new knowledge and practices and strengthened the inter-disciplinary and organisational relationships that are critical to an effective family violence response system. As a result, Victoria’s financial counselling workforce is achieving positive safety and financial wellbeing outcomes for victim survivors of family violence.

Source: Women’s Legal Service Victoria

Box 2: Local implementation for the Shepparton Specialist Family Violence Court

In establishing the Shepparton Specialist Family Violence Court (SFVC) a local operational committee (the committee) was created to oversee service integration at the SFVC, to monitor and respond to local issues and risks, and to support problem solving between the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria and SFVC stakeholders. The committee is chaired by the Shepparton Family Violence Lead Magistrate and SFVC Manager, and membership includes the Regional Coordinating Magistrate, Senior Registrar, SFVC Practice Manager, Koori Family Violence Practitioners, Victoria Police, Victoria Legal Aid Managing Lawyer and a representative from the local Community Legal Centre and Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service.

In Shepparton, ahead of the construction of safe waiting areas for the SFVC, the committee needed to identify a safe waiting space in the building for affected family members. The committee agreed to do physical walk-throughs of different hearing scenarios, with members of the committee given different roles to test the practicality of the different spaces available. Through this testing with group members, a space in the level two area was identified as the most suitable. Later, throughout the construction process, the committee continued to discuss and influence operational processes and other practical issues such as placement of signage. When the build was complete, the committee organised training and information sessions for stakeholders.

‘The local governance groups enable all stakeholders to make informed decisions about new services which impact them and are in the best interests of the communities they serve. The networks which develop from governance groups grow sophisticated working relationships that enable all stakeholders to tackle emerging issues in an informed, co-ordinated and collaborative way.’

- Managing Lawyer, Victoria Legal Aid, Shepparton

The relationships formed between stakeholders in the committee played a crucial role in ensuring the smooth operation of the court throughout coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic restrictions. The group had the ability to make key decisions and changes swiftly while considering the needs and views of key stakeholders. In September 2021, a snap lockdown was announced for Shepparton on a Friday, meaning no parties would be allowed into court on the Monday. The committee worked together to identify solutions for how the court would operate during the lockdown period to ensure it could continue to deliver an uncompromised model to the community. This included detail on how both affected family members and respondents could still access the court practitioners and legal services as required.

Source: Magistrates’ Court of Victoria

Two other examples of strong collaborative approaches that were raised through our consultations are:

- The development of resources and training for primary healthcare providers in the implementation of the MARAM and family violence information sharing reforms, led by the Safer Families Centre in collaboration with the Department of Health, Department of Education and Training, Family Safety Victoria, Domestic Violence Victoria, the Royal Australian College of GPs (VIC faculty) and WEAVERs (lived experience group). In partnering with the Safer Families Centre, government recognised the importance of utilising external expertise to tailor the resources most effectively for the general practitioner and primary healthcare workforce.

- An assessment of the evidence relating to the Royal Commission’s recommendation that government consider whether Victoria Police should be given the power to make Family Violence Intervention Orders in the field (recommendation 59),9 led by the Department of Justice and Community Safety. Several sector stakeholders who sat on the advisory group established to inform the review praised the collaborative approach taken. They particularly commented on the careful planning, strong communication and responsive consultation that ensured the recommended position was informed by an understanding of practice issues and implications of the proposal for people experiencing the system.

Endnote

9 Recommendation 59 – The Victorian Government consider [after five years] whether Victoria Police should be given the power to issue

Family Violence Intervention Orders in the field, subject to the recommended Statewide Family Violence Advisory Committee and Family

Violence Agency advising that Victoria Police has made significant improvements to its response to family violence, taking into account

the Commission’s recommendations.

Visibility of reform progress

Visibility among sector stakeholders

Stakeholders acknowledged that there is a difficult balance between the breadth and depth of focus within governance of such a broad reform program. While welcoming the role of the Family Violence Reform Advisory Group in collaboratively progressing priority areas, this has come at the expense of stakeholder visibility of the reforms as a whole. Over the last two years, there has been limited knowledge among sector representatives of family violence work being undertaken within health, education, Victoria Police and, to a lesser extent, the rest of the justice system, with much of the visibility in relation to Family Safety Victoria–led work.

Terms of reference for the advisory group state that its role is to advise government on ‘system level impact of family violence reforms and make recommendations to achieve an improved whole-of-system approach to prevention and response’.10 In order to fulfil this role, advisory group members need high‑level information about progress in implementing the different elements of the reform and future planned activity to be provided by departments and agencies. Rather than using meeting time to provide this information (as occurred in the former steering committee), written reports could be provided in the papers and taken to be read, with a portion of the meeting agenda devoted to discussion of reform interdependencies, management of implementation risks and opportunities to strengthen integration between reform elements [relates to action 2].

There is also a need to consider communication of the reform effort for the stakeholders who are not represented on the advisory group. Reducing the number of advisory group members has been key to supporting more collaborative engagement; however, as a result some stakeholders who previously had access to regular information about reform implementation no longer do. Two stakeholders, who previously sat on the Family Violence Steering Committee but are not members of the reform advisory group, gave examples of the impact of prevention campaigns on demand for their services. Having visibility of when these campaigns will be run allows them to plan to meet the increased service demand. While advisory group members will disseminate information to the groups they represent, there may be value in reviewing coverage of the current arrangements and considering whether any supplementary communication is needed.

Visibility within government

As with the external governance, within government, senior executive oversight has until recently focussed on Family Safety Victoria–led projects (MARAM and information sharing, the Central Information Point, the Industry Plan and The Orange Door network). The broadened remit of the Family Violence Reform Board to oversee the reforms as a whole, which takes effect in February 2022, is a positive development to improve oversight of the integration of the different parts of the reform and strengthen management of reform-wide strategic risks and issues. The approach to reform-wide risk management has been raised in past Monitor’s reports, and although there has been an articulation of some risks – such as workforce and system demand – in government materials, there is not currently a formal process in place to identify and manage strategic risks at the whole-of-reform level (as opposed to the individual project level). In practice, the Family Violence Reform Interdepartmental Committee has not performed this function over the past two years [relates to action 5]. Priority now needs to be given to establishing a reform-wide risk and issues identification and management process, as well as a framework for the referral of risks and issues to the Reform Advisory Group and for their escalation to the Victorian Secretaries Board.

Project-level reporting to the former Family Violence Reform Interdepartmental Committee also ceased in June 2021 as part of the move to annual outcomes reporting. However, there remains a need for the reform board to have oversight of implementation progress across the breadth of the reform, in addition to monitoring achievement of reform outcomes. This function will become even more important when the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor function ceases. The next 12 months provide an opportunity to embed strong oversight processes within government’s internal governance. We note the intent for bi-monthly project-level reporting to the reform board from 2022 and expect that this will also support communication with sector representatives on reform progress and future activity.

Finally, during 2021 there was frequent delegation of attendance by reform board members, although attendance at Family Violence Reform Interdepartmental Committee meetings was more consistent. This suggests that the priority being given to family violence, in among the many competing demands on senior executives, may not be as strong as it has been previously. Consistent attendance at reform board meetings is important for ensuring continuity of discussion and accountability for decisions and actions [relates to action 6]. With many of the reform structures now in place, commitment at the senior level remains critical to ensuring the difficult work of embedding structures and processes in organisations and driving integration in the system progresses. Without this commitment, the substantial effort and funding committed to date will not fully achieve the outcomes intended by the Royal Commission and articulated in the 10-year plan. Discussion at the last reform board meeting of 2021 indicated that the group is conscious of this challenge, while work underway to map the board’s work plan for 2022 will assist members to plan their time commitments.

Endnote

10 Family Violence Reform Advisory Group, Terms of Reference (April 2021).

High-level internal governance within departments and agencies

Individual departments and agencies have a range of governance structures in place to oversee implementation of their family violence reform initiatives, and to feed into whole-of-reform governance bodies. As all departments and agencies are responsible for implementing the MARAM framework, we have focussed on comparative governance arrangements for this aspect of the reform.

Family Safety Victoria is the lead agency responsible for creating the workforce development strategy and foundation knowledge guidance around MARAM and providing implementation support for workforces. Individual departments and agencies are responsible for implementing the framework within their portfolios, including for external organisations funded to deliver services on their behalf. Implementation of MARAM is in various stages across government, with some workforces (for example, Child Protection, mental health and many justice workforces) prescribed in September 2018 and others (for example, education and hospitals) more recently prescribed in April 2021.

The 2020 Process Evaluation of the MARAM Reforms11 report identified ’governance to drive accountability and continuous improvement’ as one of three key activities in the MARAM program logic and outlined the following necessary system components:

- governance structure for implementation and continuous improvement

- reporting and oversight for accountability

- processes to collect, gather and analyse data.

The MARAM process evaluation also made several recommendations aimed at strengthening coordination and oversight.12 In response, Family Safety Victoria has made a number of changes to how it supports and monitors MARAM implementation progress and holds organisations to account (noting that Family Safety Victoria is not a regulator), including:

- clarifying roles and responsibilities between Family Safety Victoria and implementing departments

- supplementing the internal-to-government MARAM and Workforce Director’s Group that provides cross‑government oversight of the implementation of the MARAM Framework (along with the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, Industry Plan and the Strengthening the Foundations: First Rolling Action Plan 2019–2022), with monthly bilateral meetings with departments to discuss any implications, challenges or questions that have arisen in the process of implementing the framework

- extending funding through allocation of the 2020–21 state budget for centralised teams within government departments that are responsible for prescribed workforces to drive implementation activity

- developing an annual forward-implementation plan template for departments to outline planned workforce numbers and training, expenditure and key deliverables. A quarterly reporting template was also developed to enable departments to provide a snapshot (by way of traffic light system and brief commentary) on implementation actions, budget expenditure, training, information sharing demand, and any risks and issues identified.

Implementation plans were produced for the first time in 2021 and the first quarterly reports were considered by the MARAM and Workforce Director’s Group at the November 2021 meeting. The reports are designed to be used to identify gaps or themes in the reforms that need to be addressed. Family Safety Victoria has indicated that it is proving extremely useful in supporting its visibility of implementation progress and issues in departments and agencies.

Table 1 represents department and agency MARAM governance structures and processes aligned to the necessary governance system components identified in the 2020 MARAM process evaluation.

Most departments have dedicated governance bodies (and associated working groups) in place to oversee implementation of their MARAM obligations, noting that the Department of Health is still in the process of establishing its new governance following machinery-of-government changes. There is some variation in established reporting against implementation activity and data provided to those governance bodies. The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing has reporting against detailed implementation activities and timeframes, training data for different workforces, and tables a risk and issues log for discussion at steering committee meetings. The Magistrates’ Court of Victoria provides monthly project reporting to the recently established Courts Family Violence Reform Project Board, following changes to its internal governance structure. The Department of Education and Training also provides high-level reporting on MARAM implementation as part of a consolidated child safety and family violence report, while MARAM risks and issues are formally escalated to the project control board as required. Similarly, the Department of Justice and Community Safety provides high-level MARAM reporting through a consolidated family violence implementation tracker.

Outside of structured reporting, there was also evidence of discussion about implementation progress and issues at many governance groups. Some departments provided us with their 2021–22 implementation plans and advised that the MARAM quarterly report template established by Family Safety Victoria is being used as a key reporting mechanism for governance bodies. While the implementation plan and quarterly report templates are an excellent resource to support cross‑government management of risks and issues, for effective oversight within departments and agencies, governance bodies require oversight of the more detailed planning that (presumably) feeds into these documents. For example, the annual implementation plan template does not include timeframes for activities to track progress against, and many activities are described at a highlevel rather than the detailed breakdown needed for planning and monitoring implementation delivery [relates to action 13].

There is a need for departments and agencies to ensure they are using their governance bodies to actively monitor and manage implementation progress, risks and outcomes based on detailed implementation planning. It appears there could be improvement in the reporting that some internal governance bodies receive on MARAM implementation to enable them to perform this function.

Table 1: Department and agency MARAM governance against necessary governance system components

| Agency | Governance structure for implementation and continuous improvement | Reporting and oversight for accountability | Processes to collect, gather and analyse data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Families, Fairness and Housing | Dedicated governance structure: MARAM and Information Sharing Alignment Steering Committee |

Structured reporting provided to steering committee. MARAM alignment dashboard with progress against detailed activities and timelines as well as workforce training data Risk and issues log as part of steering committee meeting papers |

Workforce training numbers collected Self-audit tool not used to date |

| Department of Justice and Community Safety |

Dedicated governance structure: Family Violence Coordination Group and MARAM and Information Sharing Working Group |

Some structured reporting provided to coordination group High-level MARAM information as part of broader family violence implementation tracker Risk and issues communicated to |

Workforce training numbers collected Self-audit tool not used to date |

| Department of Education and Training | Dedicated governance structure: Child Safety and Family Violence Project Control Board |

MARAM alignment plan endorsed by Project Control Board April 2021 Structured reporting provided to High-level MARAM progress as part of child safety and family violence priorities update report MARAM implementation risks included in department-wide risk register. Framework for escalation of risks and issues to Project Control Board |

Workforce training numbers collected Self-audit tool not used to date |

| Department of Health |

Still to establish dedicated governance structure following machinery-of-government changes Governance of Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (which incorporates MARAM alignment for hospitals) has continued |

Reporting through Family Safety Victoria whole-of-government process |

Workforce training and satisfaction numbers collected Self-audit tool distributed for use by all health prescribed organisations and workforces |

| Magistrates’ Court of Victoria |

Dedicated governance structure: Courts Family Violence Reform Program Board Courts’ governance substantially revised September 2021 |

Structured reporting provided to program board. Monthly project status reporting against project milestones, key project activities/deliverables, budget, risks and issues* |

Workforce training numbers collected Self-audit tool not used to date |

| Victoria Police | No dedicated governance structure | Reporting through Family Safety Victoria whole-of-government process |

Workforce training and satisfaction numbers collected Self-audit tool not used to date |

* Also includes MARAM implementation within the Children’s Court of Victoria

Sources: individual departments and agencies

To support the diverse range of prescribed organisations to sustain successful alignment to MARAM, the MARAM and Workforce Directors Group recently agreed to the development, and key features, of a MARAM Alignment Maturity Model. This work appears to be the continuation of work that Family Safety Victoria commenced at the time of the launch of MARAM in September 2018. The maturity model will address a key recommendation from the MARAM process evaluation13 and includes products such as a maturity matrix and a self-audit tool (building on the existing audit tool, discussed below) to enable services to map where they are on that matrix. In the interim, an Organisational Embedding Guide, released in June 2020,14

aimed to ‘directly address uncertainty around the concept of alignment’15 and provides some support for agencies to assess their level of implementation maturity. The guidance includes a self-audit tool that asks organisations to assess their progress against a series of milestones, organised according to the four MARAM pillars, to help identify where to focus implementation attention. The self-audit tool provides an important source of information to assist departments and agencies in understanding their progress and prioritising future implementation activity.

Other than a trial of the current MARAM self-audit tool within the housing area of the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, we are not aware of any other government areas having used the tool to assess alignment progress for their workforces and inform planning of future implementation activity [relates to action 13]. However, we understand that the self-audit tool is being used by a number of community sector organisations to guide their alignment activity and has been distributed to prescribed health organisations. Continuous improvement is a critical component of the MARAM framework, and priority should be given to embedding it in implementation planning and governance oversight by departments and agencies.

Endnotes

11 Cube Group (2020): Family Safety Victoria: Process Evaluation of the MARAM Reforms, Final Report (unpublished).

12 For example: Recommendation 1.5: FSV consider options for monitoring compliance with prescribed organisations’ obligations (and how those obligations have been determined) at a sector-by-sector level and at a local level (for example, through Regional Integration Committees); Recommendation 2.2: The Steering Committee should impose greater scrutiny on status reporting and a clearer process for managing delays; Recommendation 5.7: FSV should focus on providing clarity around the expected outcomes for MARAM, ensuring outcomes are being met and providing oversight and change management advice for implementation to agencies.

13 Cube Group (2020): Family Safety Victoria: Process Evaluation of MARAM Reforms, Final Report (unpublished). Recommendation 4.1: FSV prioritise the development and finalisation of a MARAM alignment maturity model to provide a common language for organisational improvement and clear expectations regarding the maturity of alignment expected from prescribed organisations. It should include a clear description of priority areas for effective organisational alignment with MARAM, foundational activities/elements within each priority and definitions for various stages of maturity across each of the priorities.

14 Family Safety Victoria: Available at vic.gov.au/maram-practice-guides-and-resources (accessed 5 December 2021).

15 Cube Group (2020): Family Safety Victoria: Process Evaluation of MARAM Reforms, Final Report (unpublished).

Primary prevention governance

Prevention work is often overshadowed by the substantial and more immediate urgency of response activity, and there is an ongoing challenge of ensuring there is sufficient space and focus given to prevention within combined governance structures. The priority given to prevention within the Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023 (prevention is one of 10 priority areas within the action plan) and the Family Violence Reform Advisory Group’s specific focus on prevention are welcome. However, we believe there is a need to further consider internal-to-government governance of prevention work across the interconnected areas of family violence, violence against women, gender equality, sexual harm and elder abuse to ensure strong coordination and oversight of effort [relates to action 7].

The Office for the Prevention of Family Violence and Coordination within the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing and Respect Victoria are jointly responsible for leading delivery of Victoria’s Free from Violence Strategy, which aims to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women (see Figure 3). There is shared responsibility for some Free from Violence initiatives with partners including Family Safety Victoria, the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector, the Department of Education and Training, the Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions. A cross-government working group, with representatives from a broad range of departments and agencies, supports coordinated delivery of initiatives within government but does not have a decision-making or formal accountability role. The Family Violence Reform Advisory Group and Primary Prevention Sector Reference Group (co-chaired by Respect Victoria and the Office for the Prevention of Family Violence and Coordination) (see Figure 2) provide forums for sector stakeholders to contribute to the direction and delivery of prevention activity relating to family violence and violence against women. The recent inclusion of prevention within the Family Violence Reform Board’s remit elevates prevention within the family violence reform governance and provides an opportunity to strengthen governance over the Free from Violence Strategy.16 The addition of Respect Victoria as a member of the reform board from February 2022 will also strengthen oversight and integration of prevention within the broader reform program given its role as a lead agency for primary prevention.

To further strengthen prevention governance, we believe consideration should be given to the reform board having formal oversight and accountability for the Free from Violence strategy, and receiving reporting on strategy implementation (in line with other reform reporting) to support its oversight role. Under these arrangements the Primary Prevention Working Group should report directly to the reform board rather than the policy steering committee.

In September 2021, the Victorian Law Reform Commission released its report Improving the Justice System Response to Sexual Offences.17 The report makes a range of findings and recommendations relating to understanding and awareness of sexual assault (including within schools through the Respectful Relationships initiative) and the governance of sexual assault reforms. The Department of Justice and Community Safety, in partnership with Family Safety Victoria, is developing a whole‑of‑Victorian-Government strategy to address sexual violence and harm. The strategy will incorporate the government’s response to the Law Reform Commission’s recommendations, delivery of a sexual assault strategy committed to under the Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–202318 and other relevant initiatives, and spans both prevention and response. A Deputy Secretary–level Interdepartmental Committee has been established to govern this work. Respect Victoria is not a member of this group because the agenda has focussed on Cabinet‑in‑Confidence work, with the Office for the Prevention of Family Violence and Coordination representing primary prevention on the committee and engaging with Respect Victoria in the development of the strategy. There are clear intersections and substantial overlap between the scope of prevention effort within the family violence reform and both the forthcoming sexual violence and harm strategy19 and Victoria’s Gender Equality Strategy. There is also a need to formally engage other government partners who are not currently part of the existing family violence reform governance, but who have a role in progressing primary prevention within their portfolios, such as the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions, and Sport and Recreation Victoria. Engagement is required at a senior level to ensure organisational support for the strategies and to provide a commitment to, and accountability for, effort and resources to implement initiatives.

To further strengthen prevention governance within the family violence reform, we believe consideration should be given to the reform board having formal oversight and accountability for the Free from Violence Strategy and receive reporting on strategy implementation (in line with other reform reporting) to support its oversight role. Under these arrangements, the Primary Prevention Working Group would formally report directly to the reform board, rather than the policy steering committee. It will be important that the prevention work being overseen by the Family Violence Reform Board and Sexual Assault and Harm Interdepartmental Committee is aligned, effectively coordinated and is not duplicative. Respect Victoria – as a lead primary prevention agency across both areas – should have a formal role in developing the sexual harm strategy as it relates to prevention, and in its governance. In re-examining the governance structures for primary prevention going forward we expect that the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing and the Department of Justice and Community Safety will consult with their partners, including Respect Victoria, in determining the most robust approach.

Endnotes

16 There has not been a governance body responsible for overseeing and making decisions relating to the Free from Violence strategy (see also section 5).

17 Victorian Law Reform Commission (2021): Improving the Justice System Response to Sexual Offences. Available at lawreform.vic.gov.au/project/improving-the-response-of-the-justice-system-to-sexual-offences (accessed 16 December 2021).

18 Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (2020): Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023. Available at vic.gov.au/family-violence-reform-rolling-action-plan-2020-2023 (accessed 5 December 2021).

19 A disconnect between elder abuse in the family violence context and institutional abuse of elders (i.e. in aged care) was also raised by one stakeholder, along with the lack of visibility of elder abuse within family violence strategy and policy.

Victim survivor inclusion

There has been real progress in the inclusion of victim survivor voices in the reform, and the operation of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council has evolved and been strengthened since its establishment. In speaking with Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council about its operation and individual members’ involvement in reform governance groups, many examples of positive improvements have been identified, including:

- The provision of pre-briefings in advance of formal engagement sessions to assist members to understand the issue they are being consulted on (particularly where there are complex written materials provided) and support their considered contribution to the consultation.

- The work of the secretariat, provided by Family Safety Victoria, to create consistency in the approach to managing engagements, including assisting departments and agencies bringing matters to the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council on how they engage with members.

- Inclusion of two (rather than individual) Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council representatives on governance groups for support and to increase the diversity of victim survivor perspectives brought to the meetings.

The Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council members were uniformly positive about the support provided by the Secretariat, and also of the respect and welcome shown in their presence at governance groups, which can often feel daunting to attend. One member commented:

‘…[the Secretariat] live in the world of bureaucracy and have to deal with non-bureaucratic people. They need to be praised for the approach that they take with us.’

There is also now a greater diversity of voices included on the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council; for example, there has not previously been a sex worker representative. However, having a council of 15 members as the primary mechanism for including victim survivor voices can limit the diversity of the lived experience expertise that is accessed by government. The Royal Commission recommended that victim survivor voices be included in policy design and service delivery, not that this be delivered through a victim survivors’ council. Under the ‘council’ model there is a challenge for the single representatives of broad communities with diverse experiences such as LGBTIQ+, disability and youth. Members feel the responsibility of representing those communities as best they can but cannot bring the full range of experience to their roles. Some members also commented that their experience of the family violence and justice systems was some time ago and, while they still bring a valuable perspective, there needs to be a place for the voices of those with current experiences. There was consensus among members of a need to bring in the voices of a wider range of victim survivors to properly reflect the diversity and currency of experience in family violence reform work. As one member stated:

‘We are some voices, we are not all voices.’

We have highlighted examples of victim survivor inclusion across different areas of the reform in previous Monitor’s reports, and other examples are provided in the government’s Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023.20 We concur that within government there is an important opportunity to build on the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and develop additional mechanisms for engaging a wider range of victim survivors in reform implementation and oversight across government. We note the work underway within Family Safety Victoria to develop — in partnership with the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council members — a lived experience strategy to ‘build on the knowledge and insights gained through the formation and strengthening of Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council to support the workforce to embed lived experience’21 initially within Family Safety Victoria and then more broadly across government. The inclusion of more diverse voices will add greater depth to the work and broaden reach to other vulnerable women, children and communities.

Certainly, in our monitoring, having Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council members facilitate access to other victim survivors with recent experience of the issues we are examining has been of enormous value, and is one potential mechanism [relates to action 9].

Additionally, there is value in considering separate approaches to hear the perspectives of those who have used family violence in developing perpetrator responses. As one Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council member commented:

‘...[perpetrators are] the problem and need to be part of the solution.’

We support this sentiment, noting that there is real complexity in how to do this in a way that ensures victim survivor safety and maintains accountability for those who have used family violence. Although, we are not aware of existing models in Victoria or other jurisdictions where perpetrator perspectives have been included in a range of family violence research work.22

We also spoke with Berry Street’s Y-Change Lived Experience Consultants, who are a group of young people who work to challenge the thinking and practices of social systems through their lived experience, advocacy and leadership. They continue to advocate for partnerships with children and young people in the ongoing development of the reform and expressed frustration that decisions that affect children and young people continue to be made without their direct involvement. This is a missed opportunity to meaningfully engage and partner with children and young people to create policy and service responses that work for them [relates to action 9]. The Y-Change Lived Experience Consultants also highlighted the importance of taking the time to build ongoing relationships with children and young people to build trust and reciprocity. In doing so, this does their experiences justice by advocating in partnership with them.

The Y-Change Lived Experience Consultants particularly highlighted that service responses for victim survivors are not designed for children and young people as individuals in their own right, only as an extension of their parent or caregiver. This issue will be further explored in our subsequent victim survivor response report. Two other areas were raised with us where collaborative partnerships with children and young people would be especially beneficial to ensure the responses developed adequately cater to their needs and concerns: service responses for adolescents who have used violence in the home; and primary prevention relating to consent and respectful relationships, including in settings outside of schools given that many children and young people in vulnerable situations are excluded from education. While the Department of Education and Training’s inclusion of student voices in its governance for the implementation of the Respectful Relationships program in schools is a positive development, there is an opportunity for this work to go further through working with victim survivors to develop guidance and resources for schools on supporting children and young people experiencing family violence. As an example, Y-Change Lived Experience Consultants partnered with Safe and Equal to develop a recently released resource to help family violence practitioners better support children and young people with experiences of family violence.23

In respect of the approach taken by departments and agencies to engaging with the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council on aspects of the reform, there remains some inconsistency in the depth of consultation and in reporting back on what has happened as a result of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council involvement. Some engagements continue to present to the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council about what is happening rather than genuinely seeking members’ involvement in understanding the issue and shaping the approaches to address it. Members explained that this makes them feel they are being consulted out of obligation rather than a genuine desire to ground the work in victim survivor experience or that they are expected to support a predetermined position. There is a strong desire among members for genuine co-design to happen more frequently, and would result in more meaningful development of priority work across government. When consulting the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, departments and agencies should ensure they provide feedback on how members’ contributions have been used and what the outcomes have been [relates to action 15]. Other examples given to us of how engagement with the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and other lived experience groups can be enhanced include providing clear consultation questions, writing up themes, consolidating findings and ideas from consultations to take back for validation and further development, and co-developing position papers resourced by the areas consulting.

Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council members also expressed a strong desire to have more autonomy in establishing their work program; to be able to raise issues that matter to the communities they represent and contribute to the relevant areas of the reform, rather than have their involvement determined by the matters that departments and agencies choose to bring to the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council [relates to action 8]. Such a role is in keeping with the government’s commitment to hearing the voices of lived experience and understanding how victim survivors experience the system in progressing the reform program.24

Endnotes

20 Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (2020): Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023: Lived Experience. Available at vic.gov.au/family-violence-reform-rolling-action-plan-2020-2023/reform-principles/lived-experience (accessed 5 December 2021). There are other examples of committees and governance structures that include people with lived experience of family violence, such as the Victims of Crime Consultative Committee (VoCCC) Victims of Crime Consultative Committee, Victims of Crime Victoria, which includes members with lived experience of family violence and sexual assault, and the Legal Services in The Orange Door Network Project, which embeds lived experience in both the Project Team and Project Control Group.

21 Family Safety Victoria: Lived Experience Strategy Concept Brief Draft, November 2021(unpublished).

22 See for example, the Centre for Innovative Justice (2018): Bringing Pathways Towards Accountability Together – Perpetrator Journeys and System Roles and Responsibilities. Available at cij.org.au/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/bringing-pathways-towards-accountabilitytogether-perpetrator-experiences-and-system-roles-and-responsibilities-170519.Pdf; ANROWS (in progress): Transforming Responses to Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence: Listening to the Voices of Victims, Perpetrators and Services. Available at anrows.org.au/project/transforming-responses-to-intimate-partner-and-sexual-violence-listening-to-the-voices-of-victims-perpetrators-and-services/ (accessed 5 December 2021).

23 Safe and Equal: Support for Children and Young People. Available at safeandequal.org.au/resources/support-for-children-and-young-people/ (accessed 10 February 2022).

24 Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (2020): Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023: Lived Experience. Available at vic.gov.au/family-violence-reform-rolling-action-plan-2020-2023/reform-principles/lived-experience (accessed 5 December 2021).

Aboriginal self-determination

Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families 2018–2028 is the key Aboriginal-led Victorian family violence agreement. It commits Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services and government to work together and be accountable for ensuring that ‘Aboriginal people, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence’. The Dhelk Dja three-year action plan sets out the actions and supporting activities required to progress the Dhelk Dja Agreement’s five strategic priorities (see Figure 4). Each of these priorities recognises the need to invest in Aboriginal culture, leadership and decision making as the key to ending family violence in Victorian Aboriginal communities.

Figure 4: Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way Strategic Priorities

- Aboriginal culture and leadership

- Aboriginal-led prevention

- Self-determining Aboriginal family violence support and services

- System transformation based on self-determination principles

- Aboriginal-led and informed innovation, data and research

Source: Based on Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families Agreement 25

The Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum was established to make key decisions, advance the strategic priorities and monitor progress against the agreement.26 The forum meets three times a year and is attended by the 11 Dhelk Dja Action Group chairpersons and Aboriginal community organisations, which make up the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus, along with representatives from government departments and agencies. Co‑chairing arrangements are shared on a rotating basis between the Dhelk Dja chairpersons and the Deputy Secretary and CEO of Family Safety Victoria. Working groups, aligned to the agreement’s five strategic priorities, progress delivery of initiatives under the Dhelk Dja three-year action plan in collaboration with the Aboriginal Strategy Unit within Family Safety Victoria. Some of the positive features of the operation of the forum that we have observed are:

- the inclusion of a broad range of voices from Victoria’s Aboriginal community in the forum and its associated action and working groups

- meeting of Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus prior to the forum to set the agenda

- respectful and robust representation of different perspectives from the community at forum meetings and Family Safety Victoria’s responsiveness to matters raised by Aboriginal forum members