Adequacy of funding for family violence work in Victorian Aboriginal communities was an area of particular focus for the Royal Commission. The Royal Commission found that the sustainability of Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention efforts were being undermined due to a lack of long-term funding:

The Commission is concerned that many positive prevention initiatives are not funded to scale, or are reliant on one-off or short-term funding. This diverts organisational effort into chasing what are relatively small amounts of funding compared to the costs of family violence to government overall. It also dilutes trust in the stated commitment the Victorian Government has made to working with Aboriginal communities to end family violence.

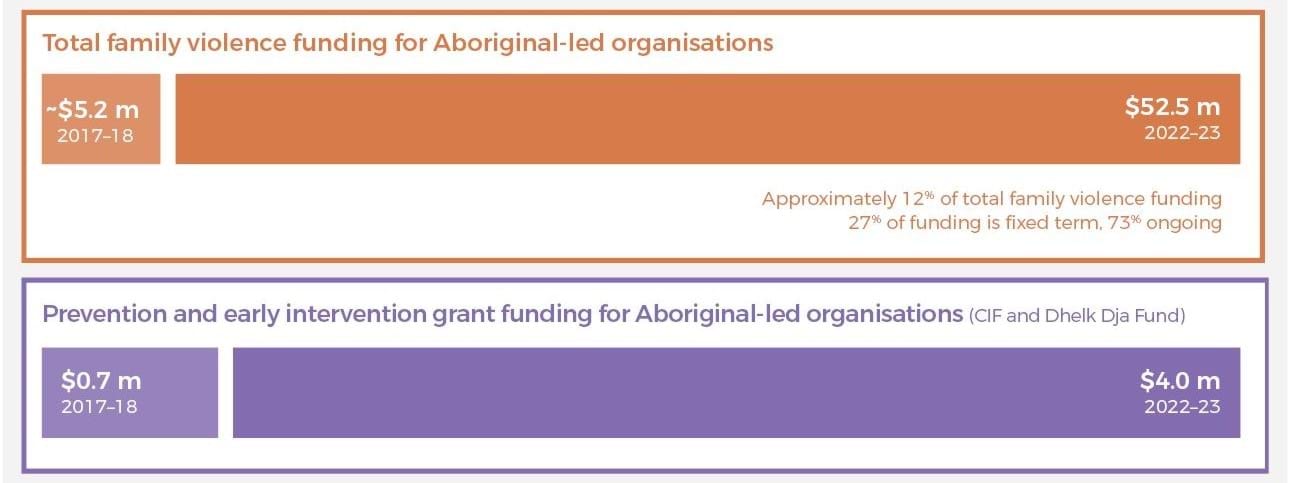

Since the Royal Commission, there has been a substantial increase in total family violence funding (encompassing prevention, early intervention and crisis response/recovery) provided to ACCOs. Between 2017–18 and 2022–23, there has been a 10-fold increase, from approximately $5.2 million to approximately $52.5 million (see Figure 14), which includes new service delivery functions arising from the family violence reforms such as The Orange Door network. In 2022–23 family violence funding provided to ACCOs represented approximately 12 per cent of total family violence funding. A proportion of this funding was also ongoing rather than fixed term, noting that – as described below – this largely relates to response services rather than prevention/early intervention.

It is not possible to accurately separate out funding dedicated to prevention and early intervention activity in the figures presented in Figure 14; however, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing has confirmed that the majority is allocated to service delivery responding to family violence. Additional funding allocation for the Community Initiatives Fund and the creation of the Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund, as outlined earlier, has substantially increased grant-based funding for Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention projects – growing from $0.65 million in 2017–18 to approximately $4.0 million in 2022–23.1 While the increase in both overall family violence funding for ACCOs and grant funding for Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention projects is positive, we are unable to judge the sufficiency of this investment without further modelling of the investment required to address family violence within and against Aboriginal communities. However, seven years on from the Royal Commission, ACCOs still cite short-term and insufficient funding as one of the biggest challenges in their family violence work. As one stakeholder expressed:

You can have all the frameworks but if you don’t have the investment, you won’t make any progress – frameworks have to be operationalised.

Figure 14: Family violence funding provided to Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations

Source: Data provided by the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

Notes:

- Total funding figures presented above relate to funding agreements between Aboriginal organisations and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing as the primary funder of family violence services in Victoria. Funding provided directly to organisations by other Victorian Government departments and agencies and the Commonwealth Government is not included in these figures.

- The 2017-18 figure for total family violence funding for Aboriginal-led organisations is approximate due to the distributed nature of funding at the service level across the department. Both figures exclude funding for services to Aboriginal Victorians provided by mainstream organisations.

Short-term grants continue to be the primary mechanism for funding Aboriginal-led prevention and early intervention initiatives. The prevention mapping report illustrated that funding for Aboriginal-led prevention was spread over more than 100 ACCOs, with many implementing a single initiative with only a modest budget. More than two-thirds (69 per cent) of organisations were funded to implement a single prevention initiative, and for most initiatives (72 per cent) the funding awarded was less than $50,000. Highlighting issues with sustainability, the mapping analysis found that most initiatives (about 80 per cent) operated for 12 months or less, reflective of the Community Initiatives Fund being the main funding source because funding is limited to a maximum of 12 months.

In our consultations, the following concerns were raised regarding the current grant-based approach to funding for prevention and early intervention:

- Narrow scope/definition of prevention: Much of the prevention work undertaken by Aboriginal organisations is not formally funded by government or recognised as ‘family violence prevention’ work, such as activities promoting connection to culture and resilience. The outcomes being sought are often broader health and wellbeing outcomes (which include but are not limited to family violence) that sit across a number of government portfolios. This integrated holistic approach doesn’t fit with government’s funding models. Grant funding also typically comes with set program eligibility criteria that do not necessarily accord with areas of greatest need in the community. The Department of Premier and Cabinet’s Coronavirus Aboriginal Community Response and Recovery Fund was cited as a positive recent initiative because it allowed organisations to put forward proposals based on community need rather than having to fit them to inflexible funding criteria.

- Lack of ongoing funding for proven initiatives: As many funding opportunities involve piloting ‘new’ or ‘innovative’ activities, organisations have commented that ‘we get good at re-branding’ effective initiatives to be able to continue to get funding to deliver them. This in turn detracts from the development of innovative programs because organisations need to use innovation funding to support their existing programming. It also impacts on the strategic delivery of initiatives to address community needs because initiatives can only run when funding is available.

- Diverting resources from funded activity: According to stakeholders, time spent preparing grant applications to access funding diverts staff resources away from delivering the services that they are funded for. We also repeatedly heard, particularly from smaller organisations, that grant funding typically doesn’t include any allocation for staffing, so implementing and overseeing initiatives must be managed with the limited number of core staff employed with base service delivery funding. However, Family Safety Victoria has confirmed that prevention grant funding can cover implementation and administration resources, suggesting there is a disconnect that needs to be addressed around how the funds can be used, and capacity building that needs to occur for grant applicants.

- Burdensome reporting requirements: Stakeholders reported a substantial problem with multiple funding streams that have burdensome reporting requirements. During consultations, we were given an example of Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service having 17 different funding streams from one department to be reported against (see Box 10). This is a particular problem for small organisations that, as mentioned above, draws resources away from funded service delivery.

Box 10: The challenge of managing multiple funding streams

For the 2021–22 financial year the Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Health Service had 17 different funding streams with one government department. From these 17 activities, it had 26 different targets to report against that required using three different client management systems and multiple reporting templates. The service also had reporting requirements for its federally funded programs, funding from other government departments, philanthropic partnerships and grants under the Community Initiatives Fund. The service indicated that they knew of other Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations across the state managing over 30 different funding streams. This represents a huge administrative burden for a small organisation.

Source: Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service

- Unintended negative consequences from short-term interventions: The very nature of short-term funding means that it requires rapid implementation in a timeframe that is too brief to show real outcomes. Stakeholders reported that short-term implementation is disruptive to ACCOs, their staff and communities. Newly engaged participants become discouraged when they can no longer participate in valued activities after funding ceases, and short-term employment contracts contribute to financial and psychosocial instability for families in the community, causing social harm.

- Inadequate funding for data collection and evaluation: Grant funding doesn’t always include allocations to support data collection and evaluation of initiatives. Where it does, the allocation is typically limited; for example, one ACCO said the evaluation component is between $2,000–$5,000. This amount is insufficient to bring in independent evaluation expertise and means organisations are left having to do the work themselves without necessarily having the internal capacity to do so (particularly in smaller organisations). Building evaluation and data management capacity within ACCOs requires sustainable funding to develop staff capability and is critical for establishing an evidence base for effective initiatives and supporting strategic investment.

A reliance on short-term grants is not confined to Aboriginal-led prevention efforts. Our companion report, Primary Prevention System Architecture, identifies that much mainstream prevention funding is also short-term and grants-based. However, the Royal Commission was especially clear that there needed to be ongoing, sustainable funding for Aboriginal-led prevention efforts in the family violence sector.

As a priority the Victorian Government should ensure that early intervention and prevention programs that have the confidence of the community and have been positively evaluated receive ongoing funding so that this work can be undertaken with certainty and scaled up to the level required.

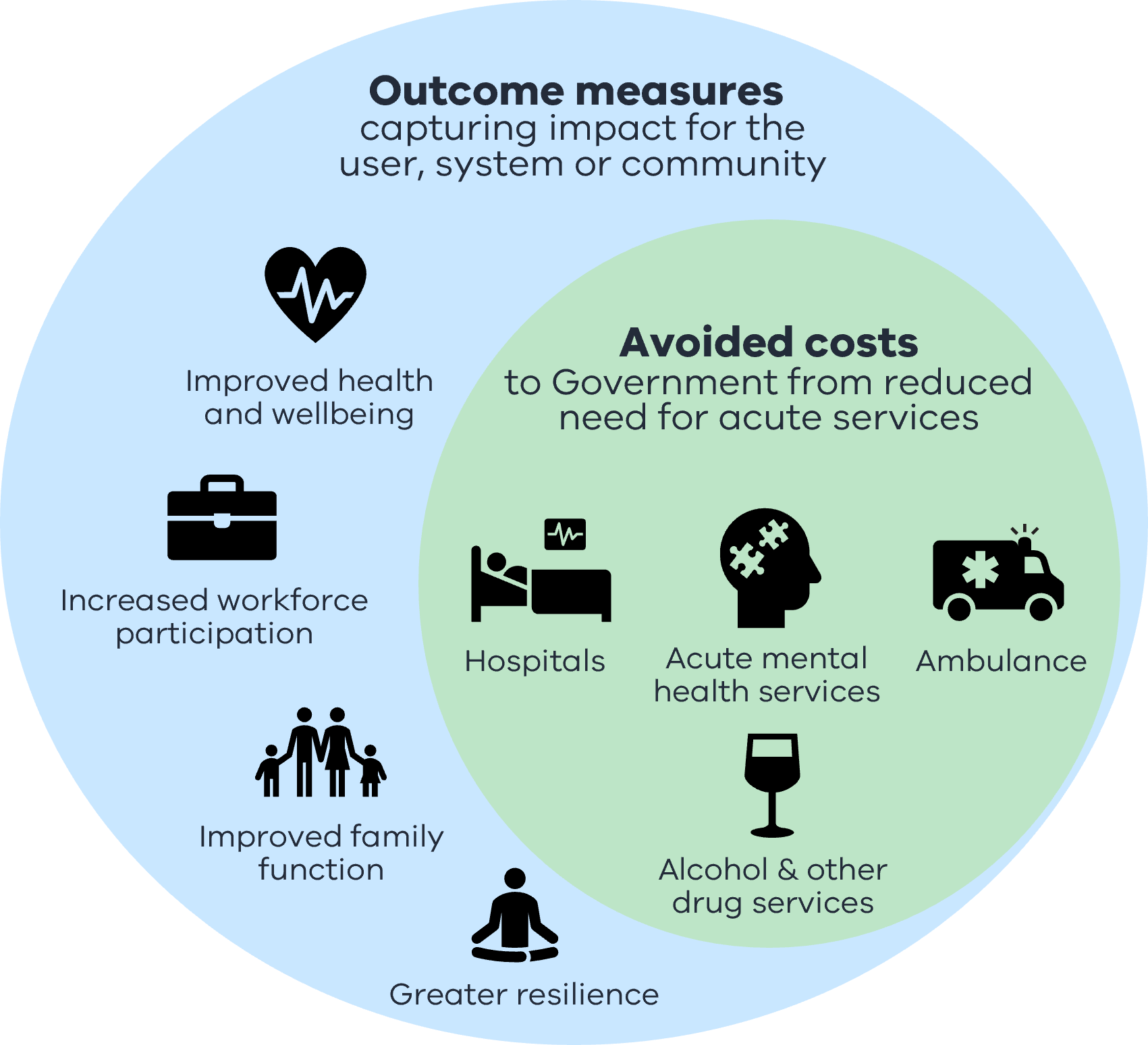

There is an urgent need to move away from grant-based funding for prevention and early intervention effort to a model of longer term funding of agreed initiatives [relates to action 2]. Stakeholders believe there is now sufficient basis to scale up successful initiatives as part of a more coherent and coordinated strategy that identifies a set of core prevention and early intervention components to be delivered within regions. A robust operational framework for Aboriginal-led prevention efforts, as recommended earlier in this report, could provide a blueprint for long-term investment in proven programs and support development of the 10-year Aboriginal investment strategy committed to under the Dhelk Dja Agreement. This approach is also consistent with the Victorian Government’s early investment framework (see Figure 15), which is designed to incentivise evidence-based investment and reinvestment in early intervention and focuses on achieving broad outcomes across multiple portfolio areas.

While the challenges of the current funding approach have been well-recognised, there are different views on how to best to fund prevention and early intervention activity. One stakeholder believed that family violence prevention should be closely linked to basic service provision:

Prevention work addresses the social determinants of health including (but not limited to) responding to housing concerns, inequities in education, employment, health and justice. These portfolios span across multiple departments within state government. Single funding agreements that are based on outcomes would enable Aboriginal self-determination, allowing ACCOs to respond to community need instead of being burdened with reporting requirements.

Respect Victoria, however, notes the risk that without dedicated funding, the most urgent response work can take precedence, leaving primary prevention with inadequate focus and resources. Another stakeholder suggested that funding dedicated prevention staff in ACCOs may be a solution for ensuring prevention is not overshadowed by response work. Opportunities for workforce capacity building are examined further in the next section; however, the approach to sustainable funding of prevention and early intervention initiatives needs to be considered in the context of the strategic direction established by the prevention framework and theory of change and government’s early investment model. In whatever funding model is established, organisational effort to develop, implement, collect and analyse data, and monitor and evaluate initiatives needs to be provided for.

Another priority for funding reform is streamlining funding agreements between the Victorian Government and ACCOs. As highlighted above, multiple funding streams, each with their own reporting requirements, are onerous for organisations to manage administratively and take staff time and effort away from service delivery. The Department of Justice and Community Safety has taken steps to address this in its funding agreements with Aboriginal-led organisations, moving to single, multi-year funding agreements that cover multiple program and service delivery areas and include streamlined reporting.

There is also an acknowledgement within government more broadly that current funding arrangements are burdensome. The Department of Premier and Cabinet commissioned a report on Aboriginal funding reform to identify opportunities to improve funding arrangements. We understand that in response to the report, individual departments with more substantial funding relationships with the project’s participating ACCOs are to lead the trialling of new funding models. Work is currently underway within the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, under the Korin Korin Balit Djak strategy, and the Department of Health, in collaboration with the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, to streamline their funding agreements. While the long-term goal should continue to be for a single cross-government funding agreement for each funded organisation, as outlined in the 2019 funding reform report, as individual departments progress their respective agendas, it will be important that there is some alignment and consistency in the approach being taken [relates to action 3]. This should make use of learnings from the work already undertaken within the Department of Justice and Community Safety.

Footnotes

- 2017–18 figures relate to the Community Initiatives Fund allocation, while 2022–23 figures include the Community Initiatives Fund and Preventing the Cycle of Violence stream projects under the Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund.

Updated