Introduction

Part 11 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (the Act) provides the legal basis for the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Risk Management (MARAM) Framework. It empowers the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence to approve a family violence risk assessment and management framework and requires organisations prescribed as framework organisations to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with that framework.1

As explained in Chapter 1, a clear legislative framework is necessary to support services to understand and comply with their legal responsibilities.

This chapter considers the extent to which the legal provisions in Part 11 of the Act are sufficiently clear to support the MARAM reforms. It also discusses the clarity of related subordinate legislation, including the Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018 (the Regulations) and the legislative instrument which codified MARAM as the approved framework.2

The effectiveness of Part 11 in promoting consistency in family violence risk identification, assessment and management is discussed further in Chapter 6. Stakeholder concerns about aspects of the MARAM Framework and associated resources and tools are outlined in Chapter 7.

Clarity of Part 11

The legal provisions in Part 11 are mostly clear, but the MARAM legislative instrument lacks clarity about what organisations must do to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance, and tools with the MARAM Framework

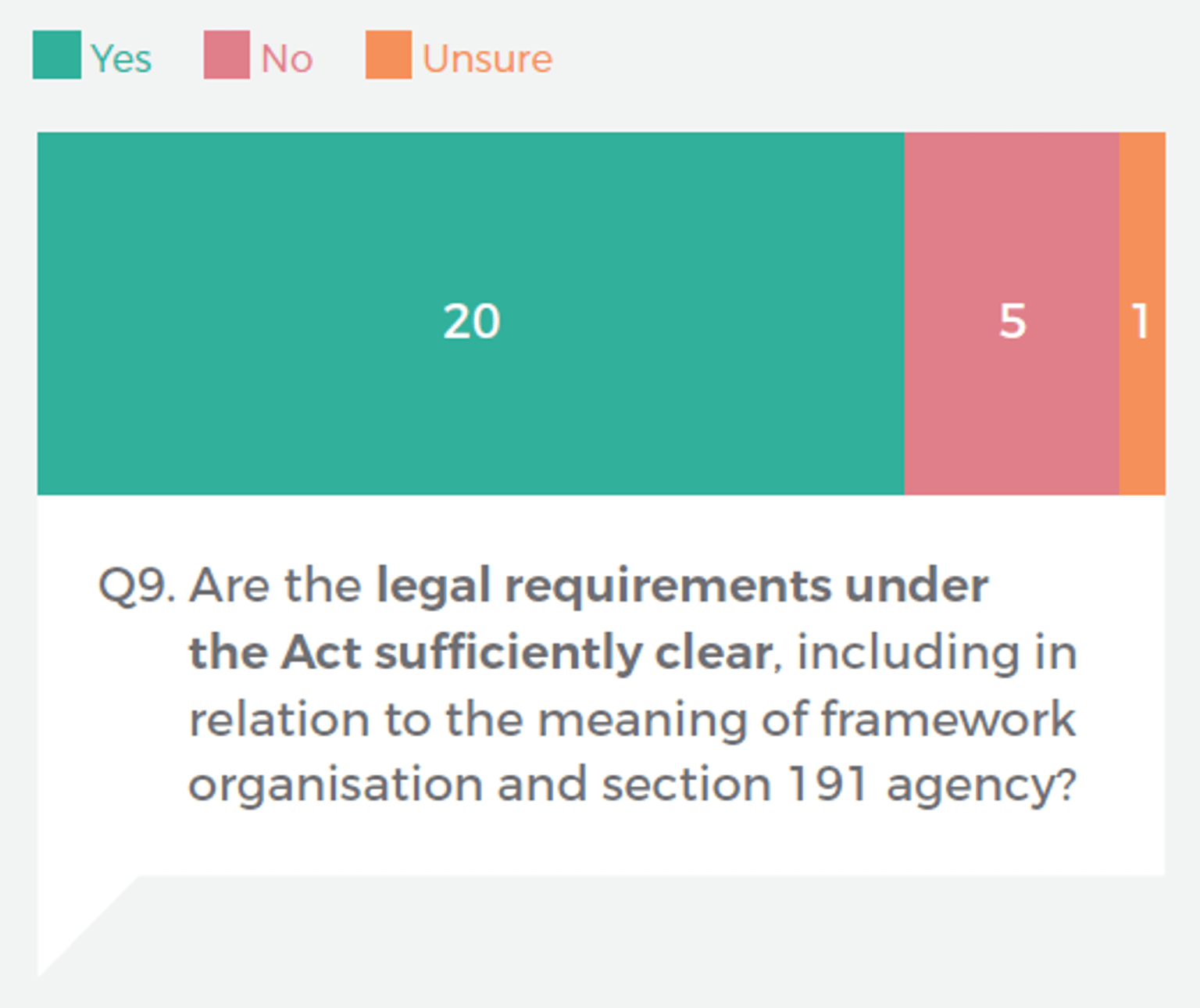

Most stakeholders considered that the legal provisions in Part 11 are clear. As shown in Figure 20, 77 per cent of submitters addressing this question believed that the Act is clear.

Submission responses that did not consider the Act to be sufficiently clear cited the need for awareness raising and tailored guidance to assist understanding of the Act’s requirements. Submissions also noted that the approach to prescribing framework organisations by reference to funding sources created confusion. This is discussed further below and in Chapter 1.

Berry Street – Take Two Therapeutic Family Violence Services suggested that the terms ‘information sharing entity’ (ISE) and ‘risk assessment entity’ (RAE) should be used to describe organisations that must align with MARAM, reflecting the terminology used in the sector.3 We agree that the terms ISE and RAE appear to be more commonly understood by stakeholders. This was evident during our consultations and in responses to our call for submissions campaign, with many respondents failing to identify themselves as a framework organisation notwithstanding that they are prescribed as such. In contrast, nearly all stakeholders who are ISEs or RAEs were able to identify this.

Notwithstanding this, we do not recommend any legislative change to the definition of framework organisation. We recognise the need to legally distinguish between ISEs/RAEs and framework organisations. This is important because some individuals or organisations are currently only prescribed under either Part 5A or Part 11. This is discussed further below. In our view, any confusion about the meaning of framework organisation is best addressed by government through ongoing training and education.

Some stakeholders who reflected that the Act is clear nonetheless highlighted challenges or confusion about MARAM alignment. Although stakeholders understand they are required to align with MARAM, they are unclear on what alignment itself requires. This was particularly raised by organisations prescribed under phase 2, although some phase 1 organisations identified similar concerns.

Common feedback indicated uncertainty about:

- how the MARAM Framework applies to a specific organisation, or to individual prescribed programs within a broader organisation that includes non-prescribed programs

- the specific actions that are required to align with the MARAM Framework

- where a specific organisation should be in their alignment journey.

For example, we heard from Ambulance Victoria that, as a unique service, interpretation and contextualisation is required to implement MARAM. Without clear guidance or a compliance framework outlining minimum standards it is challenging to understand Family Safety Victoria’s alignment expectations. Other stakeholders reflected that because alignment is not defined in the Act, and in the absence of anything concrete in the Act or a specific contractual obligation regarding alignment, there was significant leeway in the steps organisations could take to align resulting in organisations having different views about whether an organisation has aligned.

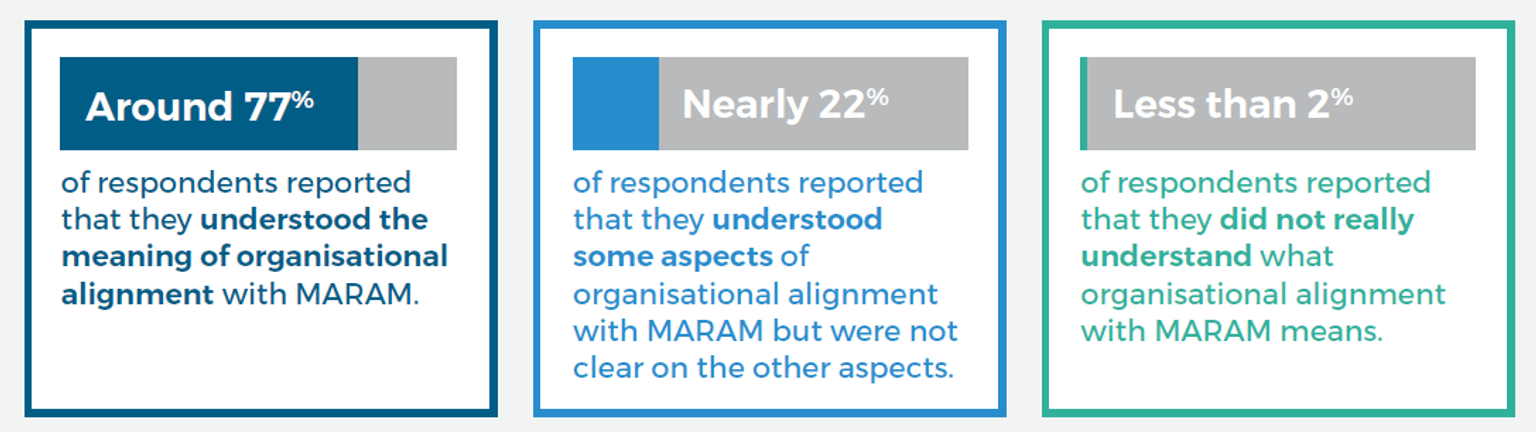

A degree of uncertainty about alignment was reflected in the results of the most recent MARAM Framework Annual Survey conducted by Family Safety Victoria in 2022, as shown in Figure 21.

Although it was pleasing to see a high proportion of respondents reflecting their understanding of MARAM alignment, we consider there is still a significant number of respondents who do not fully understand what alignment requires. We also note that as this survey involved self-reporting by organisations, the results do not necessarily show a consistent understanding of what alignment requires across the sector. As noted, we heard that some organisations have different views on whether an organisation is, or is not, aligned with MARAM.

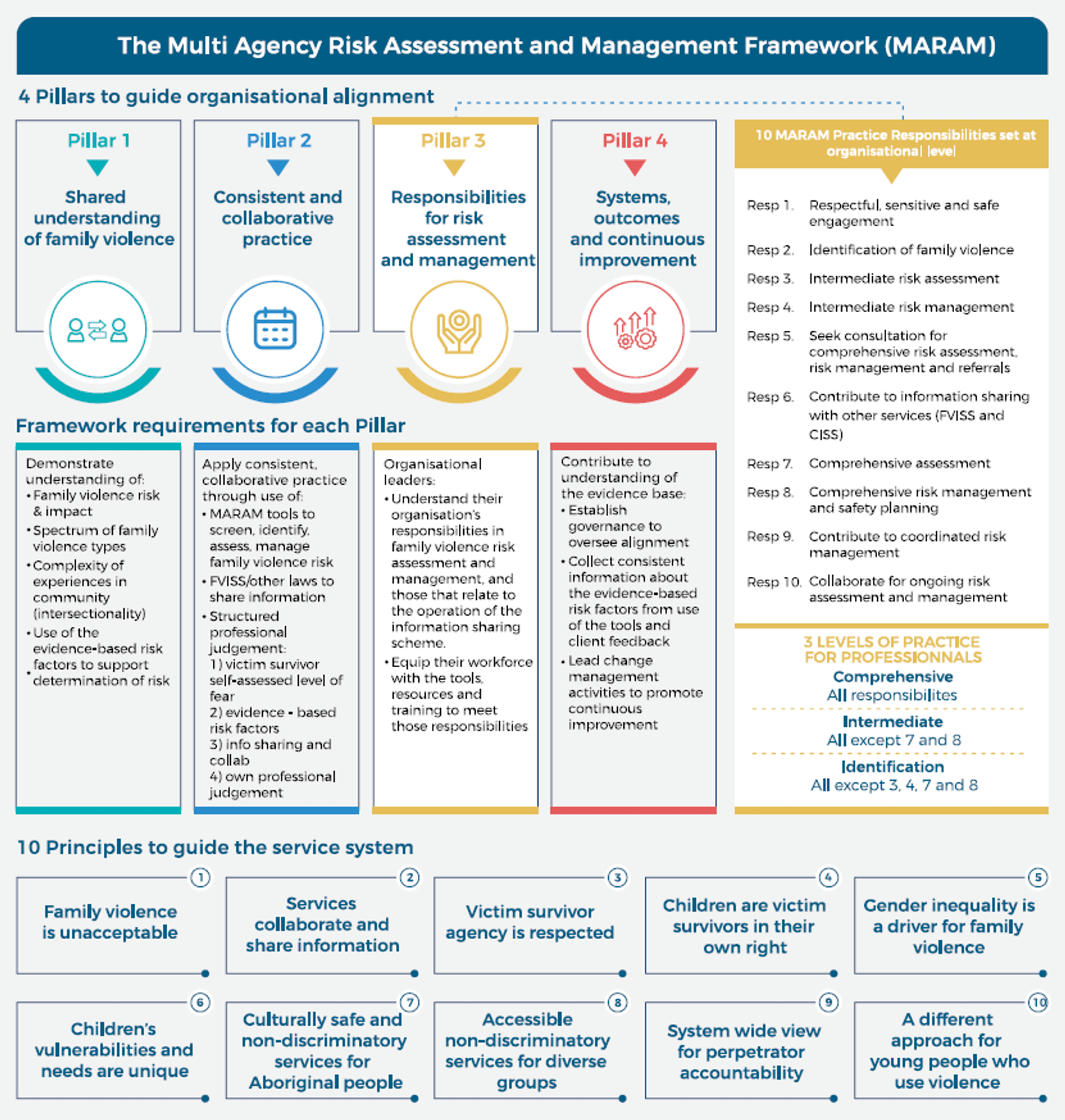

In our view, uncertainty about MARAM alignment is at least partly a result of the way in which the Act and legislative instrument describe the requirement to align with MARAM. Under the Act, framework organisations must align their relevant policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the MARAM Framework as set out in the legislative instrument.4 As shown in Figure 22, the legislative instrument:5

- outlines 10 principles that underpin the MARAM Framework

- specifies framework requirements that apply under four pillars

- outlines 10 responsibilities for risk assessment and management, including expectations of framework organisations under each responsibility.

The legislative instrument also lists recognised family violence risk factors, including high-risk factors. More information about the 10 principles underpinning MARAM and the 10 responsibilities for risk assessment and management is set out in Appendix 5.

One of the purposes of the legislative instrument is to “support framework organisations … to understand their roles and responsibilities”.6 However, the legislative instrument is silent on how framework organisations meet their obligation to align. There are no references within the legislative instrument to how or when framework organisations should align their policies, procedures, practice guidance or tools with the MARAM principles, pillars, risk factors and responsibilities.

We acknowledge the considerable work undertaken by Family Safety Victoria to provide guidance to framework organisations, including through a MARAM Framework policy document.7 The policy document defines alignment as “[a]ctions taken by Framework organisations to effectively incorporate the four pillars of the [MARAM] Framework into existing policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools, as appropriate to the roles and functions of the prescribed entity and its place in the service system”.8 There are also many tools and guides available to support understanding of MARAM alignment.9 This includes checklists for organisational readiness and MARAM alignment, a MARAM responsibilities decision guide and mapping tool, a guide for embedding tools into existing practice, MARAM policy and procedure examples, family violence leave policy considerations, and a guide to build external partnerships.

Family Safety Victoria also developed an organisational embedding guide, which comprises various resources and tools that outline specific actions framework organisations can take to align with MARAM. The embedding guide includes:

- a MARAM organisation self-audit tool to support framework organisations to assess their current progress towards MARAM alignment

- a project implementation plan, to be based on activities identified through the self-audit

- an implementation review guide to support organisations to review the success of implementation activities.

We also recognise that Family Safety Victoria is currently developing a MARAM alignment ‘maturity model,’ as recommended in the June 2020 process evaluation of the MARAM reforms.10 The maturity model will build on the organisational embedding guide and provide a means for framework organisations to assess their level of progress in alignment with MARAM.

Notwithstanding the volume of available guidance and support, our view remains that it is difficult for organisations to ascertain from the Act and legislative instrument what steps they are legally required to take to align with MARAM. Recognising that phase 2 organisations are still early in their alignment journey, and that work is underway on the maturity model, we considered whether the best approach would be to leave the Act and legislative instrument as currently drafted. Although this would allow organisational understanding of MARAM alignment to continue to develop over time, it would not address current stakeholder concerns about the lack of clarity about alignment. It could also lead to inconsistencies if the maturity model is not adopted by all framework organisations, noting that the maturity model would not have any legal status or be binding on organisations.

Further, we believe that where legislation imposes a requirement on an individual or organisation, it is best practice that the requirement be sufficiently clear and specific. We therefore considered legislative options to provide greater clarity and specificity to ensure a consistent understanding of MARAM alignment across the sector.

We considered amending the Act to introduce specific activities that organisations must do to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the MARAM Framework. Although this would provide certainty, we do not recommend this approach. Noting that the MARAM Framework will be reviewed every five years to ensure it continues to reflect best practice, we believe the Act needs to be sufficiently flexible to accommodate ongoing changes to MARAM as the evidence base around family violence risk continues to grow.

We believe that a better approach is to amend the legislative instrument authorising MARAM as the approved framework so it better supports framework organisations to understand their roles and responsibilities. As legislative instruments can be more readily amended than Acts, this approach will enable changes to be made more quickly.

We recommend that the legislative instrument clearly sets out steps and activities that organisations must take to align with MARAM. These steps and activities would then become mandated as part of a framework organisation’s obligation to align with MARAM. This approach has several advantages. It provides a clear obligation and certainty about what is required. It also promotes greater compliance by imposing a legal obligation to take certain steps, rather than relying on guidance provided through non-binding policy materials. This will ensure a consistent approach across all framework organisations and therefore promote consistent risk assessment and management practices across sectors.

We acknowledge the need for flexibility within the legislative instrument to account for the vast differences in roles and responsibilities among framework organisations. The way in which one sector or organisation aligns with MARAM will look different from the way another sector or organisation aligns, recognising that there is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach. However, we believe that greater specificity is possible and would support organisational understanding and consistency of MARAM alignment.

It is beyond the scope of this review to determine exactly what steps and activities should be included in the legislative framework, noting that this will require further consultation with stakeholders. We also note that careful drafting will be required to ensure the legislative instrument is sufficiently clear and does not impose vague obligations, noting the importance of clarity in the law. Where possible, we suggest that specific actions be drawn from the existing guidance available to framework organisations such as the milestones and examples listed in the MARAM alignment organisation self-audit tool.11 The development of the maturity model provides a further opportunity for Family Safety Victoria to consider specific actions that show progress in MARAM alignment, and that could be incorporated into the legislative instrument.

As previously noted, a MARAM best practice evidence review is currently underway and will include consideration of the evidence base in the MARAM Framework legislative instrument. We suggest that changes to the legislative instrument be progressed after the best practice evidence review is complete. This will enable any recommended changes made in that review to be implemented concurrently, thereby minimising the impact on stakeholders. Given our suggestion that the updated legislative instrument draw from the maturity model, we note that changes to the legislative instrument should also be progressed after the maturity model is developed. We recognise that this will not provide immediate clarity but consider it important that alignment requirements are considered in detail before amending the legislative instrument.

Recommendation 13: That the legislative instrument authorising MARAM as the approved framework under Part 11 of the Act be amended to clearly set out the steps and activities that framework organisations must take to align with MARAM.

Clarity regarding who must align with MARAM

The Regulations specify which organisations are prescribed as framework organisations and must therefore align with MARAM. In Chapter 1, we noted stakeholder feedback that Victoria’s approach to prescribing ISEs had caused confusion in practice, including due to the functional approach to prescription and the fact that some organisations are prescribed based on their funding source. Similar issues were raised in relation to the prescription of framework organisations. For the reasons outlined in Chapter 1, we support Victoria’s functional approach to prescribing organisations.

Consistency in the prescription of organisations as ISEs and framework organisations is important to ensure information sharing is informed by an understanding of family violence and relevant risk factors

As previously noted, although the list of framework organisations is substantially the same as the list of ISEs, there are some variations. As shown in Box 7, some people or bodies are prescribed as ISEs but not framework organisations.12

Box 7: People or bodies prescribed as ISEs but not framework organisations

- Commission for Children and Young People

- Disability Services Commissioner

- Disability Worker Registration Board of Victoria

- General practice nurses

- General practitioners

- Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority

- Victorian Disability Worker Commission

- Victorian Institute of Teaching

- Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority

Source: Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018, Schedules 1 and 3.

The two Regulatory Impact Statements (RIS) for the regulations that prescribed framework organisations did not explain the basis for not prescribing some of these bodies.13 The only exception was in relation to general practitioners, where one RIS noted that individuals cannot be prescribed under the Act.14 This issue is discussed further below.

In our view, it is important that there be as much consistency as possible between organisations prescribed as ISEs and organisations prescribed as framework organisations. For a person to effectively share relevant information under Part 5A of the Act, it is important that they understand family violence risk factors and what information may be relevant to share for a family violence assessment or protection purpose. This is reflected in the Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines: Guidance for Information Sharing Entities (the Ministerial Guidelines), which outline an expectation that “persons authorised to request or share information under Part 5A should be trained in and refer to the MARAM Framework or policies, tools, frameworks or programs aligned to it”.15 Without this understanding, the risk of inappropriate information sharing increases.

Some submissions identified the benefit of MARAM alignment in supporting an understanding of when to request and share information under Part 5A. For example, The Australian Association of Social Workers cited practitioner views that “success of the information sharing scheme is predicated on the ability of professionals to identify the information that should be collected, then shared”.16 The importance of a sector-wide understanding of family violence and risk to support information sharing was also identified in the submission from No to Violence, which stated:17

Some practitioners note concerns about sharing information with other professionals as they are not confident that the information will be appropriately used or that the other professional/service has a sufficiently deep understanding of the context of family violence.

We acknowledge that some professions that are not prescribed as framework organisations have nonetheless developed guidance based on the MARAM Framework. For example, we recognise the work of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners in updating its guidance, Abuse and Violence – Working With our Patients in General Practice (commonly referred to as the ‘White Book’) to include information about MARAM and the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS).18 However, providing guidance about the MARAM Framework is quite different from a legal obligation to align policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with MARAM.

We considered whether the Act should be amended to mandate that all ISEs are also prescribed as framework organisations. Although this would ensure consistency, we do not recommend this approach. We recognise that there may be some limited circumstances in which it is appropriate to prescribe an organisation as an ISE but not a framework organisation, and we support retaining flexibility in the Act to allow for this. However, we suggest that the government further considers the current list of prescribed organisations in light of the need to promote consistency and support information sharing based on an understanding of what is risk-relevant information.

The definition in section 188 of the Act limits government’s ability to prescribe individuals as framework organisations

As noted above, we understand that general practitioners are not prescribed as framework organisations because individuals cannot be prescribed under the Act. This stems in part from the Act’s language, which defines a framework organisation as a ‘body’ prescribed as a framework organisation.19 We note that this would also currently preclude the prescription of others identified in Box 7 above, such as general practice nurses and the Disability Services Commissioner.

To ensure all ISEs can be prescribed as framework organisations in the future, we considered whether the Act should remove the current restriction on prescribing individuals. We recognise the legal complexity in prescribing individuals as framework organisations, including that some individuals would not have relevant policies, procedures, practice guidance or tools that could be aligned with the MARAM Framework. However, we note that many individuals will, in their professional capacity, rely on policies and tools in the course of their work. In our view, it is important that such policies and tools are MARAM-aligned when considering the assessment or management of family violence risk. Further, we note that the obligation to align with MARAM applies to relevant policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools and that the obligation will therefore only apply to the extent that an individual has such materials.

We recognise that the burden to align with MARAM would be greater for individuals than organisations, and that funding would inevitably be required to minimise this burden. However, we note that an individual would only be prescribed after a thorough consideration of the costs and benefits of prescribing them – for example, through a RIS process. In our view, this acts as a sufficient safeguard for individuals.

We therefore recommend that the Act be amended to allow individuals to be prescribed as framework organisations. We note that this amendment will require careful drafting to ensure individuals are only required to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools to the extent applicable to them in their professional capacity.

Recommendation 14: That Part 11 of the Act be amended to allow both people and bodies to be prescribed as framework organisations.

All organisations that are required to align with MARAM are prescribed in the Regulations rather than relying solely on contractual agreements under section 191 of the Act, with this approach providing the greatest clarity and transparency

Section 191 of the Act requires government departments and agencies to include a requirement to align with MARAM in any new or renewed contract or agreement for providing services related to family violence risk assessment or management.20 This reflected a recommendation from the Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission), which appeared to envisage that contracts and funding agreements would be used as a mechanism to ensure consistent practice, along with prescribing additional non-funded agencies.21

We understand that government has not used section 191 in this way. Although we understand that departments have updated contracts and agreements with service providers as required under the Act, these updates have simply reiterated an organisation’s obligations as a prescribed framework organisation. That is, the obligation to align does not arise independently of an organisation’s prescription, with contracts and agreements reflecting the legal requirements that exist under the Act and Regulations.

We support the approach of prescribing all organisations required to align with MARAM as framework organisations. In our view, including the obligation to align in contracts and agreements alone – without also prescribing the relevant organisations – is likely to cause confusion and uncertainty in practice and lacks the transparency of current practice. Further, the process of prescribing organisations generally requires the preparation of a RIS, which affords an opportunity for government to consider the costs and benefits of requiring certain organisations to align with MARAM.

Although section 191 of the Act may be seen as somewhat redundant in light of the government’s current approach, we do not recommend repealing it at this time. Combined with prescription, contracts and funding agreements provide an important lever for government to ensure organisations are complying with their obligation to align with MARAM. They also provide a mechanism for government to monitor or review an organisation’s progress in their alignment journey, noting there is no monitoring approach within the Act. We support retaining section 191 so it can be used in line with current practice.

Other stakeholder feedback

Many stakeholders described the MARAM resources and practice guides as overly complex. We also heard frequently that the MARAM reforms can be overwhelming for some organisations, with organisations requiring specialist support and funding to implement. Stakeholder concerns about the government’s approach to implementing the MARAM reforms are highlighted further in Chapter 7.

Although we agree that MARAM is an incredibly complex reform, ultimately it is beyond the scope of this legislative review to make any findings or recommendations on this matter. We note that the MARAM best practice evidence review is due to be completed at the end of 2023 and we suggest that this review considers how to reduce complexity within MARAM wherever possible.

Footnotes

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), sections 189, 190.

- Victorian Government, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 445, 25 September 2018.

- Berry Street – Take Two Therapeutic Family Violence Services, Submission No 25, p. 3.

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), section 190.

- Victorian Government, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 445, 25 September 2018.

- Ibid., p. 1.

- Victorian Government, Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework: A Shared Responsibility for Assessing and Managing Family Violence Risk (June 2018). We note that this document describes itself as ‘the MARAM Framework’ notwithstanding that the legal obligation to align relates to the framework as set out in the legislative instrument and not the policy document.

- Victorian Government, Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework: A Shared Responsibility for Assessing and Managing Family Violence Risk (June 2018), p. 16.

- See MARAM practice guides and resources (webpage) (Accessed 31 March 2023).

- Cube Group, Process Evaluation of the MARAM Reforms (final report, 26 June 2020), Recommendation 4.1, p. 68.

- Victorian Government, MARAM Alignment Organisation Self-Audit Tool (June 2020).

- Note that Risk Assessment and Management Panel (RAMP) participants, Multi-Agency Panel to Prevent Youth Offending (MAP) participants and the Director of Housing are also not expressly prescribed as framework organisations but are captured under other provisions. For example, the core members of RAMPs and MAPs are prescribed individually in Schedule 3 of the Regulations. Where a RAMP participant is not otherwise prescribed, they are required to follow the policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools of the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing.

- Victorian Government, Regulatory Impact Statement – Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Amendment Regulations 2018 (final report, 8 June 2018); Victorian Government, Regulatory Impact Statement – Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Amendment Regulations 2020 (final report, 17 October 2019).

- Victorian Government, Regulatory Impact Statement – Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Amendment Regulations 2020 (final report, 17 October 2019), p. 30.

- Victorian Government, Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines: Guidance for Information Sharing Entities (updated April 2021), p. 10.

- The Australian Association of Social Workers, Submission No 35, p. 7.

- No to Violence, Submission No 26, p. 10.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Abuse and Violence: Working With our Patients in General Practice (The White Book) (5th edn, 13 April 2022), supplementary chapter for primary care providers in Victoria, pp. 408–427.

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), section 188.

- Ibid., section 191.

- Royal Commission into Family Violence: Report and Recommendations (final report, March 2016), Vol I, p. 139.

Updated