Introduction

Part 11 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (the Act) aims to strengthen system-wide approaches to family violence risk assessment and management and ensure consistency of such approaches to support victim survivors.1 As previously noted, Part 11 provides the authorising environment for the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Risk Management (MARAM) Framework and the obligation on prescribed framework organisations to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with MARAM.2

Part 11 also requires portfolio ministers to report annually to the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence (the Minister) on the implementation and operation of MARAM by framework organisations for which they are responsible, with the Minister required to provide a consolidated annual report to the Victorian Parliament.3 Although not specified in the Act, we understand that the purpose of the annual reporting requirements is to promote accountability and transparency regarding framework organisations’ alignment efforts.

This chapter addresses the extent to which Part 11 has been effective in promoting consistency in identifying, assessing and managing family violence risks. It also considers the effectiveness of the annual reporting requirements as an accountability mechanism for the MARAM reforms. The last section in this chapter explores any adverse effects identified in relation to Part 11.

Consistency in risk identification, assessment and management

Through the introduction of the MARAM Framework, Part 11 has supported a shared language for family violence and a focus on keeping perpetrators in view

Many submissions reflected that MARAM has supported a shared language around family violence. Submissions highlighted that using the MARAM Framework language supports cohesive collaborative practice by helping to establish a common language to discuss family violence risks across different sectors and disciplines.

As explained by The Women’s Services Network:4

The MARAM … is a very effective way of making non-[specialist family violence] agencies aware of their responsibilities and providing a map of how to manage [family violence] risk in the community. It is very apparent in case coordination activities that more and more external agencies are aware of what [family violence] is, what their role might be in identifying, assessing and managing risk, and how the [specialist family violence service] can lead this work.

Our stakeholder consultations reinforced this view, with many stakeholders commenting that MARAM has supported organisations to talk about family violence in more consistent ways. An increased understanding of family violence was evident in an experience shared with us by a survivor advocate. The survivor advocate reported a significantly improved experience when attending the same hospital due to violence inflicted by their partner, describing the two experiences as ‘night and day’. This is explained in the case study in Box 8.

Box 8: Case study – Improved family violence response by a public hospital

When the victim survivor first attended hospital, her experience was not trauma-informed. They felt dehumanised and powerless. She was asked to discuss the violence in public spaces, resulting in the entire waiting room being aware that they were a victim of family violence. Because of the public discussion, she did not disclose that she had also been raped. Her children were also asked in public whether they had witnessed any of the violence. A notification of the violence was made to Child Protection and the victim survivor was terrified that the violence had been reported in a way that they would lose their children. Her information was also shared with Victoria Police against her wishes.

Two years later, after Parts 5A and 11 of the Act were introduced, the victim survivor attended the same hospital due to further violence. Hospital staff took her into a separate room and privately discussed what had happened and keeping the victim survivor’s information protected. The staff‘s attitude was supportive and helpful rather than judgemental and punitive. The victim survivor felt safer and more empowered and so shared more information about the family violence they were experiencing. While the hospital again notified Child Protection, this time they identified the victim survivor as a protective parent.

Source: Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor, based on an account shared with us by a survivor advocate.

Stakeholders also told us that the MARAM Framework has supported organisations to keep perpetrators in view. For example, a specialist family violence practitioner explained that Part 11 has allowed organisations to ‘flip the switch’ to focus on keeping perpetrators in view. Other stakeholders agreed, explaining that the Act has raised awareness for non-specialist family violence workers about the need to keep perpetrators in view.

Organisations working with perpetrators also reflected there is now a greater awareness and acceptance of perpetrator services, with discussions no longer solely on a victim survivor needing to leave their home to be safe and a greater focus on the changes that the perpetrator needed to make.

Where services align with MARAM, there is greater consistency in risk identification, assessment and management; however, inconsistent alignment and a lack of alignment progress is limiting the overall effectiveness of Part 11

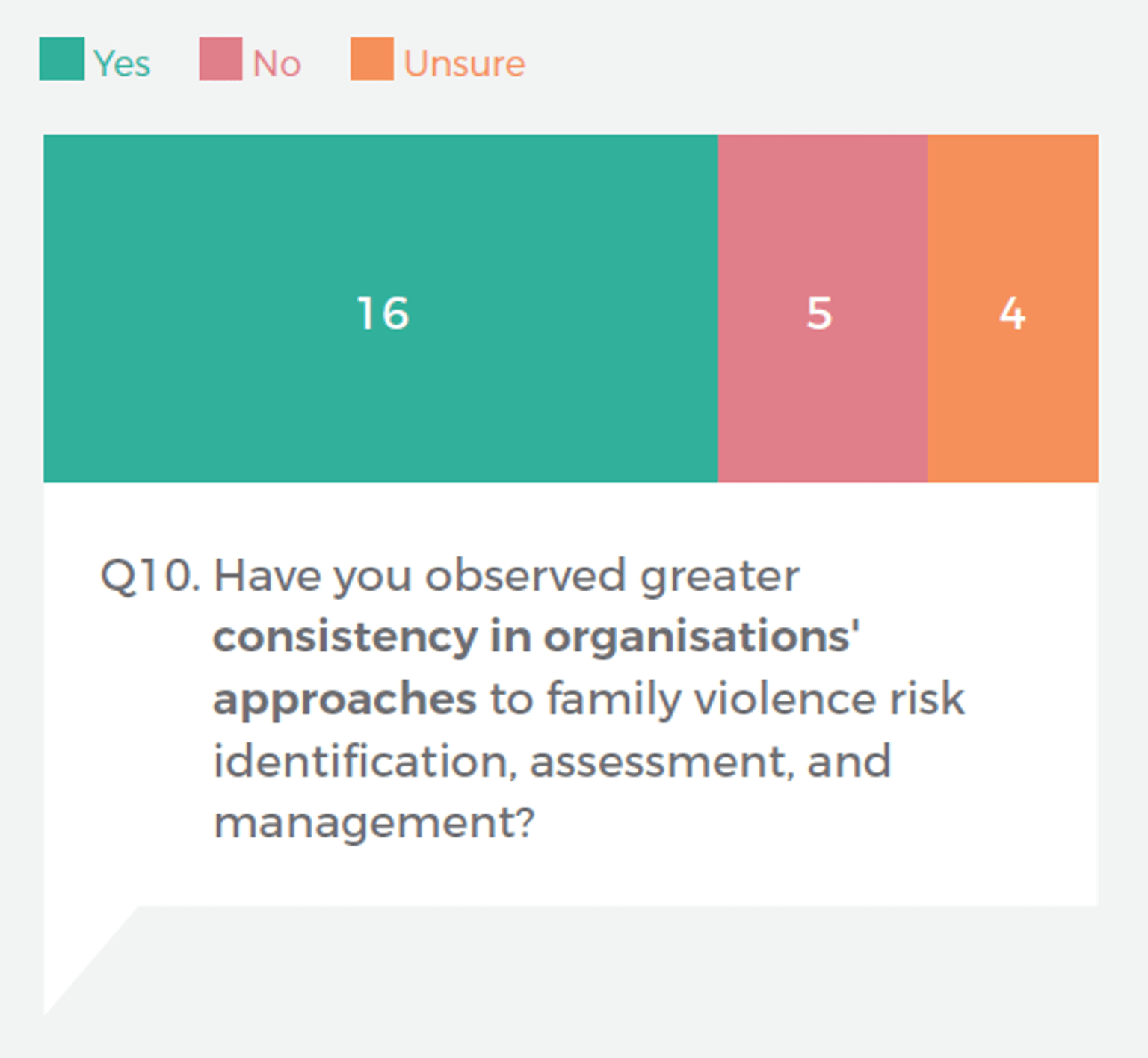

Most stakeholders reflected that, where organisations have aligned, the MARAM Framework has increased consistency in family violence risk identification, assessment and management. As shown in Figure 23, 64 per cent of submission responses addressing this question observed greater consistency.

Submissions reporting increased consistency highlighted their experiences of greater service collaboration, an increase in referrals being received with a completed MARAM risk assessment attached and a greater recognition or visibility of family violence across organisations. For example, The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre stated:5

Since the introduction of the MARAM framework, it appears that professionals across a range of services are being more pro-active in considering and identifying family violence risk much earlier, and throughout their practice … With the introduction of different levels of risk assessment; from screening and identification, through to brief and intermediate or comprehensive risk assessments, this has assisted with acknowledging that everyone has a role to play in assessing family violence risk.

In contrast, many submission respondents noted they had not observed greater consistency in risk identification, assessment or management. This was often noted to result either from inconsistencies in the way that organisations had aligned with MARAM, or a lack of alignment progress across sectors or within organisations. Submissions cited various concerns including:

- inconsistent knowledge and awareness of MARAM across organisations

- a lack of action or change in risk assessment or management practices

- underutilisation of the MARAM Framework outside of specialist family violence services

- inconsistent quality of risk assessments received from some organisations

- gaps in accurate risk identification and management for some groups in the community including older victim survivors, children and culturally diverse victim survivors

- gaps in perpetrator accountability.

In highlighting concerns, many stakeholders noted the need for training, guidance and resourcing to support consistency in practice. This is discussed further in Chapter 7.

Some submissions recognised the potential for MARAM to achieve consistency but considered this had not yet been achieved. For example, the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency stated:6

MARAM’s aims and objectives are clear, and when properly implemented should see an increased safety for people experiencing family violence, but we acknowledge the significant amount of work left to do to ensure alignment with the Framework across organisations and sectors who have responsibility to identify, assess and respond to family violence risk.

Other submissions similarly reflected that although MARAM had been effective in achieving consistency where services had aligned with MARAM, alignment itself has been inconsistent. For example, The Salvation Army stated:7

Overall, the MARAM as a tool and framework has been effective in achieving consistency in family violence risk identification, assessment, and management … Risk assessment is one component of the MARAM and while there is consistency in training for risk assessment, the MARAM as a framework is not consistently embedded in organisations.

The Salvation Army went on to explain that not all organisations obtained the same information for risk assessments, with this often depending on the individual practitioner.8 Inconsistent alignment was also observed across organisations within the same sector and between different program areas within the same organisation. For example, the Early Childhood Australia Victoria Branch noted that organisational alignment varied across the early childhood sector, while Merri Health identified differences between programs within organisations.9

The Statewide Family Violence Integration Advisory Committee (SFVIAC) explained the importance of alignment in achieving service coordination, noting that services that are aligning with MARAM remain reliant on other services they interface with to also align. They noted this can be challenging in the absence of clear accountability about when services need to be at a certain level in their alignment journey. Some SFVIAC representatives considered that organisations should be required to demonstrate that they are aligning with MARAM, with suggestions including a timeline for alignment, a monitoring system for alignment and potentially greater accountability through service agreements or accreditations.

In our view, inconsistent alignment and a lack of alignment progress is limiting the effectiveness of Part 11 of the Act. We consider that inconsistent alignment likely stems from a lack of clarity regarding what alignment requires and specific steps and activities that organisations need to take. This issue is discussed in Chapter 5. We believe that our recommended changes to add specific steps and activities into the legislative instrument authorising MARAM as the approved framework (the legislative instrument) will support greater alignment consistency.

However, maximising consistency in risk identification, assessment and management also requires that framework organisations align with MARAM in a timely manner. We acknowledge that MARAM alignment progress has in some cases been impacted by external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, workforce shortages and resourcing constraints. These issues are discussed further in Chapter 7. We also recognise that it is to be expected that some phase 2 organisations are less progressed in aligning with MARAM given they were only prescribed for 18 months at the time of consultation. However, we also heard concerns about a lack of progress in some phase 1 organisations. Some phase 1 organisations also explained that they were still in the early stages of their alignment journey, despite being prescribed for approximately four years at the time of consultation.

We consider that a lack of alignment progress within some organisations stems, at least in part, from the lack of a compliance or accountability mechanism within the Act. We considered whether the Act or the legislative instrument should be amended to introduce a timeline for alignment or a monitoring or compliance mechanism to oversee alignment. We acknowledge that it is likely that Family Safety Victoria considered these options at the time of drafting the Act and legislative instrument. We also recognise that the Act was not designed as a regulatory scheme, noting the enormous goodwill across the sector to implement the reforms. However, this legislative review provides an opportunity for fresh consideration, noting we have had the benefit of the MARAM Framework being in operation for a number of years and have been able to observe alignment progress within this time.

Introducing a timeline for alignment would have several benefits. It would send a strong message to framework organisations that they need to be actively working towards alignment and taking specific actions to embed MARAM within their organisation. Legislated timeframes would also promote compliance with the Act, noting that proposed guidance such as the maturity model would not be binding on framework organisations. By ensuring timely alignment activities, a timeline would also promote consistent practices in risk identification, assessment and management, thereby increasing the Act’s effectiveness. Conversely, without a timeline, there is no incentive or obligation on framework organisations to prioritise MARAM alignment. This can contribute to very little progress being made, with little consequence for those organisations that are not actively working towards alignment.

We therefore recommend that a timeline for MARAM alignment be introduced. In our view, it is more appropriate that the timeline be specified in the legislative instrument rather than the Act, reflecting the purpose of the legislative instrument in outlining the framework that organisations must align with. This approach also provides greater flexibility because legislative instruments can be more readily amended.

We believe that the proposed timeline should be linked to the new steps and activities to be added to the MARAM legislative instrument. We also suggest that timelines be based on an organisation’s date of prescription as a framework organisation to reflect the phased implementation approach to the MARAM reforms. This approach recognises the different levels of family violence literacy within different sectors and ensures organisations prescribed later are given enough time to align with MARAM.

In our view, it is important that timeframes be sufficiently broad to recognise that different types of framework organisations may need more or less time to undertake certain activities. This could depend on factors including an organisation’s size or functions. We suggest that timelines be expressed broadly to account for this. For example, certain activities could be required within the first year of prescription, with others required within the first one to three years. Recognising that MARAM alignment is an ongoing obligation, we note that some steps and activities could also be required periodically, such as training new staff members within a certain time after they commence employment. We also note the need for careful drafting to satisfy the requirements of a legislative instrument and to ensure there is enough clarity for framework organisations regarding timeframes.

We recognise there may be particular challenges in introducing a timeline in relation to the MARAM Framework’s continuous improvement pillar. We note that an organisation’s policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools may need to be periodically reviewed and updated to ensure they reflect current best practice approaches. However, we believe that a timeline could be flexible enough to account for this, such as by setting an appropriate timeframe to review materials within an agency. This would also support the ongoing nature of the obligation to align with MARAM.

It is beyond the scope of this review to suggest appropriate timeframes for undertaking different alignment activities and steps. This requires detailed consideration, and we suggest timeframes be developed in further consultation with framework organisations. We also strongly support providing appropriate funding, resources and training to support framework organisations in complying with the new timeline.

A timeline for alignment would be most effective if combined with an additional compliance mechanism. For example, this could include a penalty for failing to meet the specified timelines. For the reasons discussed in Chapter 2 regarding a compliance approach for the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS), we do not recommend this approach. Rather, we support increased monitoring of alignment progress through the MARAM annual report. As discussed below, greater accountability through the annual report will provide a mechanism for the community to assess how organisations are tracking with MARAM alignment. In our view, this will provide enough incentive for framework organisations to meet required timelines.

Recommendation 15: That the legislative instrument authorising MARAM as the approved framework under Part 11 of the Act be amended to introduce a timeline for alignment activities. The steps and activities to be incorporated into the legislative instrument under Recommendation 13 above should be linked to the timeline, with timeframes determined based on an organisation’s date of prescription as a framework organisation.

Annual reporting requirements

Under the Act, each portfolio minister must prepare an annual report on the implementation and operation of the MARAM Framework by framework organisations for which they are responsible.10 The report is required to include the prescribed matters, which are currently:11

- actions taken by a public entity or a public service body to support framework organisations in relation to the implementation and operation of the MARAM Framework

- a summary of implementation progress by framework organisations

- proposed future actions to be undertaken by public entities or public service bodies to support ongoing implementation and operation by framework organisations.

After receiving these portfolio reports, the Minister must prepare a consolidated annual report addressing the same matters, with the consolidated report to be tabled in parliament.12

Annual reporting in its current form does not provide meaningful information or provide accountability for framework organisations’ alignment with MARAM

The tabling of the consolidated report in parliament is intended to provide an opportunity for the government to outline to the Victorian community the progress of MARAM alignment across different sectors. This supports transparency around the implementation of the family violence reforms. Some departments told us that the reporting processes are also valuable in raising the profile of the MARAM reforms internally and as a way of reflecting on alignment progress.

As noted in the June 2020 process evaluation of MARAM, the consolidated report is intended to be used “as a mechanism to oversee alignment to the approved framework (MARAM) and to set accountability expectations for Ministers”.13 If used as an accountability mechanism, annual reporting can assist in monitoring MARAM alignment and ensure that:

- framework organisations are progressing MARAM alignment to the extent possible

- barriers or challenges to alignment are identified and potential solutions are considered

- government departments are providing appropriate support to framework organisations, reflecting their role in supporting ministers to administer their portfolios.

In examining the 2018–19 consolidated report, the process evaluation found that the report was insufficient in providing accountability.14

We agree that the annual reporting process should be a mechanism for providing accountability for ministers (through their departments) and framework organisations. As Part 11 and the legislative instrument include no other compliance measures, annual reporting is the only process that ensures framework organisations are meeting their legal obligations. After analysis of various ministerial portfolio annual reports and the 2019–20 and 2020–21 consolidated reports, we consider that current reporting remains insufficient in providing accountability.

We believe that the consolidated reports do not meaningfully explain framework organisations’ progress in aligning with MARAM, nor do they identify where challenges have arisen with MARAM alignment and how these challenges will be addressed. Some consultation stakeholders share this view. The Statewide Family Violence Integration Advisory Committee also reflected that there could be a greater focus in the report on the multi-agency nature of the reforms, and that ideally the report could include a section addressing mechanisms for measuring the effectiveness of alignment.

In part, the lack of accountability and transparency provided by the consolidated report stems from a lack of clarity in the Act and legislative framework regarding the steps that organisations must take to align with MARAM, how progress is measured, and the timeframe in which steps should occur. Similar findings in the process evaluation led to a recommendation for Family Safety Victoria to develop a maturity model for MARAM alignment,15 with this work now underway.

We have recommended above that the MARAM legislative instrument be amended to provide greater specificity for actions that framework organisations should take to align with MARAM, and a timeline for alignment. We also considered whether the Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018 (the Regulations) should be amended to require reporting of progress against these specific activities and timeframes, once developed. This would provide greater accountability and act as a monitoring mechanism for MARAM alignment. Although it is difficult to recommend specific changes to the Regulations until alignment actions and timeframes have been determined, we recommend refocusing the consolidated annual reporting requirements around the alignment activities and timeframes.

Departments raised concerns with us about the reporting burden on framework organisations. We acknowledge the substantial amount of work that some framework organisations undertake to provide information for the reports. We do not consider that any additional administrative burden should be placed on individual framework organisations. Rather, we propose a reconsideration of what information they provide to departments to support reporting.

We also believe that some of the current burden likely stems from challenges in reporting on alignment progress in the absence of clear alignment actions. Our recommended changes to the legislative instrument may help reduce the burden on framework organisations.

We heard from departments that the annual reporting process is burdensome and takes time away from other core functions including client-facing work and other MARAM alignment activities. We also heard that the timeframes for providing portfolio minister reports present challenges in preparing the consolidated report for tabling in parliament. Under the Act, portfolio reports must be provided to Family Safety Victoria by 30 September, and the consolidated annual report must be tabled in parliament within six sitting days of 1 January the following year.16

We recognise the amount of resourcing required for portfolio departments to prepare reports and brief ministers. In our view, portfolio reports are an important mechanism in ensuring departments play an active role in supporting agencies within their portfolio to align with MARAM. Although we recognise the burden on departments, and associated challenges relating to the timeframe to develop a consolidated report, we consider that portfolio reports should be retained. In our view, the burden associated with annual reporting is outweighed by the accountability that will be provided through a report that clearly articulates how framework organisations are progressing in their MARAM alignment journey.

However, we note that there may come a point at which the benefits of annual reporting no longer outweigh the burden. For example, when all or most framework organisations have fully aligned with the MARAM Framework, the need for monitoring and accountability may be reduced. At this point, we suggest that the government considers reducing the frequency of reporting. In our view, reporting would remain necessary where framework organisations are required to further update policies, procedures, practice guidance or tools – for example, to incorporate any changes to the MARAM Framework as a result of the five-yearly evidence base reviews.

Recommendation 16: That the Regulations be amended to require portfolio ministers’ annual reports and the consolidated annual report to include information about framework organisations’ progress against key alignment steps and activities and timeframes. These amendments should be progressed after the legislative instrument has been amended in accordance with recommendations 13 and 15.

Adverse effects of Part 11

No adverse impacts were identified relating to the legal provisions in Part 11

Stakeholders did not identify any adverse effects stemming from the legal provisions in Part 11 of the Act. However, we heard concerns about aspects of the MARAM Framework itself, and associated resources, tools and practice guidance. These concerns are outlined in Chapter 7.

Footnotes

- Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 23 March 2017, p. 931 (Martin Pakula, Attorney-General).

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), sections 189, 190.

- Ibid., sections 192, 193.

- The Women’s Services Network, Submission No 22, pp. 2–3.

- The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre, Submission No 27, p. 6.

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, Submission No 33, p. 3.

- The Salvation Army, Submission No 30, p. 5.

- Ibid.

- Early Childhood Australia Victoria Branch, Submission No 3, p. 2; Merri Health, Submission No 21, p. 5.

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), section 192.

- Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018, regulation 18.

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), section 193.

- Cube Group, Process Evaluation of the MARAM Reforms (final report, 26 June 2020), p. 65.

- Ibid., p. 66.

- Ibid., recommendation 4.1.

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), sections 192, 193.

Updated