Introduction

During the legislative review, stakeholders raised various challenges and concerns that were not directly connected to the provisions in Parts 5A or 11 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (the Act), but which nonetheless impacted on the Act’s effectiveness. These included:

- concerns about the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Risk Management (MARAM) Framework and associated tools

- other laws that impact on the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS)

- the non-prescription of certain organisations as information sharing entities (ISEs) for the purposes of the FVISS or framework organisations for the purposes of the MARAM Framework

- challenges related to the implementation of the Act.

This chapter discusses these issues.

Concerns about the MARAM Framework and associated tools

Stakeholders consider that aspects of the MARAM Framework do not adequately address risks for diverse communities and that MARAM risk assessments are time consuming to administer

We acknowledge the available guidance in the MARAM Practice Guides regarding the experiences of family violence across Victoria’s diverse communities. This includes guidance and information in relation to diversity, cultural safety and intersectionality, and the experiences of older victim survivors, LGBTIQA+ communities, victim survivors from culturally diverse backgrounds, people with a disability, and male victim survivors.1

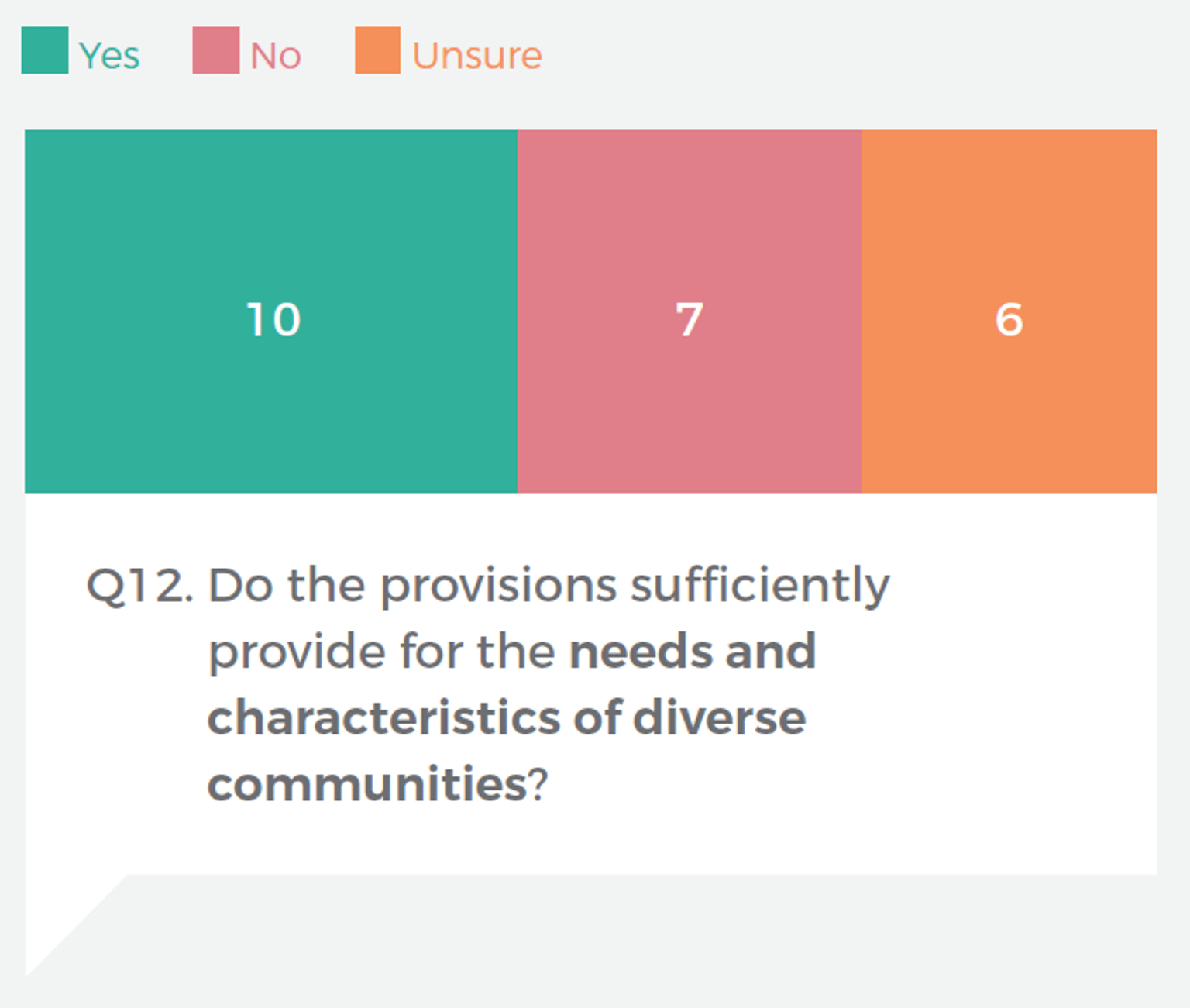

However, we also acknowledge that many stakeholders raised significant concerns about the suitability of components of the MARAM Framework for risk assessment and management across diverse communities. As shown in Figure 24, less than half of submission respondents to the Monitor believed that the Act sufficiently provides for the needs and characteristics of diverse communities. Although this question was asked in relation to Parts 5A and 11, most of the concerns raised related to the MARAM Framework.

Submissions raised concerns that MARAM is not culturally safe for members of the Aboriginal community. Services explained their need to adopt tailored approaches to increase cultural safety while working within the MARAM Framework. For example, the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency noted their work to “deepen the cultural lens of mainstream MARAM tools and guidance to contextualise for both the Aboriginal community members we work with as well as Aboriginal staff”.2 This was reinforced in stakeholder consultations. For example, a Gippsland Family Violence Alliance representative noted that in their organisation’s work with the Aboriginal community, practitioners would have conversations with clients and then take the information discussed in that conversation to complete a MARAM risk assessment at a later time.

Submissions also identified gaps in MARAM in relation to refugee, migrant and other culturally diverse communities. For example, The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre and The Salvation Army highlighted their views that the MARAM risk assessment does not adequately deal with issues such as forced marriage, dowry abuse and the different extended family structures within culturally diverse communities.3

Although not specifically stated to result from MARAM, another submission noted a lack of understanding about elder abuse across sectors. The submission explained that this can lead to the identification of risk factors being minimised or dismissed as ‘ageing’, which can increase the risk of harm for older victim survivors.4 Monash Health agreed, stating that “older people have specific needs and risks that are not adequately addressed in the MARAM guides and assessment tools”.5 Some community legal centres similarly reflected their view about the need for a greater focus on elder abuse within the MARAM Framework given the unique dynamics of this form of family violence.

Concerns about the suitability of MARAM for diverse communities were also raised in stakeholder consultations. In addition to the concerns noted above, stakeholders also expressed their views that MARAM does not support effective risk identification, assessment or management for people with a disability, members of the LGBTIQA+ community or male victim survivors.

Another common concern raised by stakeholders was that MARAM risk assessments are time consuming to administer, which has an impact on client services and has the potential to cause delays in a victim survivor’s access to support. For example, inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence explained:6

Another important issue to note is the amount of time the MARAM takes to complete for clients from migrant and refugee backgrounds. The questions that are listed on the MARAM, require nuance and care in delivery depending on the cultural and faith background of the client. Perceptions and discussions of safety, family relationships, sexual relationships and consent, can vary depending on the client’s cultural background. Furthermore, where a client also requires an interpreter present for the risk assessment, the length of time for the completion of the MARAM can be quite extensive.

The time-consuming nature of completing MARAM risk assessments has also affected the experience of victim survivors. As noted by The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre, “some clients can find it triggering and overwhelming to complete a MARAM, and … there have been instances where some clients have been unable to complete the MARAM process”.7

Given the number of stakeholders who identified issues with aspects of the MARAM Framework, and in light of the gravity of concerns raised, we strongly suggest that the five-year MARAM best practice evidence review consider these issues and consult further with stakeholders to address concerns.

Other laws and legal processes impacting on the FVISS

New laws that restrict information sharing may limit the ability of ISEs to share risk-relevant information under Part 5A

Many Victorian laws, often called ‘secrecy’ laws, restrict a person’s ability to share information. Part 5A of the Act expressly overrides some of these secrecy laws to enable an ISE to share relevant information for a family violence assessment or protection purpose.8 However, because new laws are not captured by this override provision, there is the potential for new laws to impact on information sharing under Part 5A.

An example of this occurring was evident in stakeholder feedback about the Spent Convictions Act 2021 (Vic). Many stakeholders reflected that the Spent Convictions Act has limited the ability of the courts to share relevant perpetrator information, namely criminal outcome information, that was previously being shared before the Spent Convictions Act commenced. Stakeholders spoke of this having a negative impact on risk assessment and management activities, with specialist family violence services reporting challenges obtaining information needed for safety planning.

Key aspects of the Spent Convictions Act are set out in Box 9. The Spent Convictions Act reflects the principle that “people who have worked hard to turn their lives around deserve the opportunity to move on from minor historical offending”.9 While we support this principle, we consider this should not be at the expense of victim survivor safety. We understand that the Department of Justice and Community Safety is working with Family Safety Victoria to identify options to carve out Part 5A from the operation of the Spent Convictions Act and to resolve the issues identified by stakeholders during the review. We support ongoing work to achieve this objective.

Box 9: The Spent Convictions Act

The Spent Convictions Act establishes a scheme under which a person’s criminal convictions can become ‘spent’, either automatically or by application. Certain convictions automatically become spent, either on the day the person is convicted or after a certain period.

Once a conviction has become spent, it can only be disclosed in limited circumstances provided for in the Spent Convictions Act.

Source: Spent Convictions Act 2021 (Vic), in particular sections 7–10, and 20–23.

To safeguard against new legislation limiting Part 5A’s effectiveness, we considered whether the Act should be amended to include a broader override provision. This would mean that Part 5A would operate regardless of any new information sharing restrictions or secrecy laws introduced in the future, unless those new laws were expressly stated in the Act to override Part 5A. A similar approach has been adopted in other jurisdictions. For example, under child wellbeing and family violence information sharing provisions in Western Australia, agencies can disclose relevant information despite any law that prohibits or restricts its disclosure.10 However, we understand based on advice from Family Safety Victoria that this approach was considered during the drafting of the Act but was deemed not possible in the Victorian context. We therefore do not recommend further consideration of this approach.

We also note that there is a well-established Cabinet process for departmental consultation in developing new legislation. Cabinet submissions involving legislative proposals must generally go through a ‘coordination’ process in which the submission is distributed to all departments for comment before Cabinet consideration.11 We reiterate the importance of a thorough coordination process within and between departments in developing any legislation that may impact on the Act, including ongoing consultation during the drafting of any new laws, and the provision of legal advice if required.

Stakeholders are concerned that victim survivor confidential information may be disclosed through legal processes such as subpoenas and freedom of information requests

There are some legal processes under which an ISE may be required to disclose confidential information they hold about an individual, including a perpetrator or victim survivor. This includes subpoenas and freedom of information (FOI) requests, as shown in Figure 25.12

Stakeholders cited uncertainty about the application of subpoenas and FOI requests to information collected and shared by ISEs for family violence assessment and protection purposes under Part 5A. We also heard concerns about the potential for a victim survivor’s confidential information to be disclosed through such processes and about the need to engage lawyers to respond to requests.

For example, as The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre explained:13

[W]e are aware that in some instances, perpetrators are continuing to abuse their victims through the use of information sharing legislation. For example, we are aware of an instance where [Department of Families, Fairness and Housing] Child Protection requested information from our practitioners about MARAM assessments and that information had then been the subject of a subpoena from a perpetrator’s lawyer to Child Protection. This can lead to continued abuse by the perpetrator and in this instance, the client disengaged from our services.

Another stakeholder reflected that when services are not notified that confidential information they have shared with another organisation is subsequently subpoenaed from that organisation, it is difficult to effectively safety plan with victim survivors.

The Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines: Guidance for Information Sharing Entities (the Ministerial Guidelines) provide guidance for ISEs on responding to subpoenas and FOI requests. In relation to subpoenas, they highlight the importance of organisations seeking legal advice before producing documents, set out the grounds on which a subpoena may be challenged and suggest steps ISEs can take when they have received a subpoena.14 In relation to FOI requests, the guidelines highlight an exception to providing information in response to an FOI request where disclosing a document would unreasonably disclose information about the personal affairs of another person. In considering this exception, agencies must consider whether disclosing information to an alleged perpetrator or a perpetrator would increase the risk to a victim survivor. The Ministerial Guidelines provide an example of when this may occur, including where disclosing a document may identify a victim survivor as a source of information about the perpetrator.15

In our view, the Ministerial Guidelines provide sufficient guidance for ISEs in responding to subpoenas and FOI requests, noting that an appropriate response will always need to be considered based on the circumstances of the case and, in the case of subpoenas, should be informed by appropriate legal advice. We do not consider that any changes to the Ministerial Guidelines are required.

A related challenge was raised by some stakeholders in relation to including victim survivor information on a perpetrator’s medical or clinical file. For example, the Royal Melbourne Hospital explained that victim survivors may disclose family violence to staff when visiting perpetrators who are receiving care. Sometimes hospital staff will create a separate medical record for the victim survivor to enable the hospital to record this information while protecting it from an FOI request from the perpetrator.

However, we heard that this practice is not widespread, with other hospital representatives indicating that most health services would not open a new file for the victim survivor in such circumstances. A Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence Initiative representative explained that this was due in part to the absence of clear guidance on how to separate third-party family violence risk-relevant information within patient files. Creation of new medical records is usually tied to an episode of care and requires the consent of the person to create one. Hospital staff have raised concerns about ensuring the security of third-party information being included in a perpetrator’s medical record if the medical record is subpoenaed or an FOI request is made. There are not consistent guidelines from Department of Health available for hospitals to follow (that also incorporate the episode creation rules).

We considered whether the Ministerial Guidelines could be amended to provide guidance around this issue. However, noting the need for the Ministerial Guidelines to be of general application across all ISEs, and our findings in Chapter 1 about the need to reduce length and complexity, we do not recommend this approach. We understand that the Department of Health is planning to work with Family Safety Victoria and the Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence Initiative to develop guidance for health and other relevant workforces regarding this issue. We support this work.

One stakeholder also identified concerns about information stored within the Mental Health Tribunal and the potential for information to be shared with perpetrators.16 Concerns about the disclosure of information through Mental Health Tribunal processes were also raised in the two-year review of the FVISS. The two-year review recommended that the government communicates with the Mental Health Tribunal about risks associated with disclosing a file to a perpetrator where the file indicates that family violence risk information has been shared without their knowledge under the FVISS.17 This recommendation was accepted in full by the government.18 We do not consider that any further recommendations are necessary in relation to this issue.

Some stakeholders find it challenging to navigate the different requirements of the FVISS and the Child Information Sharing Scheme

The Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) is established under Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (Vic) (CWS Act). Key aspects of Part 6A are set out in Box 10.

Box 10: CISS requirements

Organisations prescribed as information sharing entities can disclose and request confidential information for the purpose of promoting the wellbeing or safety of a child or a group of children.

Recognising the inherent intersection between information that may be relevant for a family violence assessment or protection purpose and information that may be relevant to promote child wellbeing or safety, the CWS Act expressly provides that organisations that are prescribed as ISEs under both Part 5A of the Act and Part 6A of the CWS Act can share confidential information under either the FVISS or the CISS.

Source: Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (Vic), sections 41V(a), 41W(1) and 41ZD.

Stakeholders had mixed views about whether the different requirements of the FVISS and CISS posed challenges in practice. Some stakeholders reflected that they had not experienced any challenges resulting from being prescribed under both schemes. Others told us that it was sometimes challenging to understand how to apply both the FVISS and CISS. During consultations, inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence representatives gave an example of requesting information under the FVISS and receiving information that the perpetrator had a previous allegation of sexual assault against a child. In this case, it was unclear whether it was appropriate to share this information (and to whom) when their client did not have children or contact with children.

The Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency reflected that the staging of the FVISS and CISS reforms has resulted in an uncoordinated approach to the two schemes, with this being compounded by responsibility for the schemes sitting with different government departments.19 The Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare also spoke of a lack of understanding about the intent and purposes of the CISS in comparison with the FVISS, and that the prioritisation of the FVISS over the CISS can mean that child abuse, neglect and sexual abuse of a child can be subsumed into a family violence rather than a child wellbeing framework.

The CWS Act requires the relevant minister to issue guidelines in relation to the operation of Part 6A (the CISS Guidelines).20 The CISS Guidelines include a chapter on sharing information in the context of family violence, which provides guidance for organisations prescribed under the CISS and either or both of the FVISS and MARAM reforms.21 For example, they note the relevance of the MARAM Framework working alongside other frameworks in guiding information sharing under the CISS to assess and respond to child wellbeing or safety more broadly within a family violence context.22

A detailed review of the legal provisions in Part 6A of the CWS Act and the CISS Guidelines was beyond scope for the legislative review. We acknowledge that similarly to Part 5A of the Act, Part 6A of the CWS Act must be reviewed within five years of its commencement.23 We consider that the CISS review will provide an opportunity for stakeholder views about the CISS to be explored and considered in detail. In the meantime, we support a continued focus on education and training for those workforces that are prescribed under both the CISS and the FVISS and that regularly engage with children.

Approach to prescribing organisations

The non-prescription of many Commonwealth-funded agencies and private providers as ISEs and framework organisations has resulted in a gap in family violence information sharing and risk assessment and management

In Chapters 1 and 5, we highlighted stakeholder uncertainty resulting from Victoria’s approach to prescribing organisations as ISEs and/or framework organisations. In addition to concerns about clarity, stakeholders also identified that the non-prescription of some organisations has created a gap in service provision. This was particularly raised in relation to Commonwealth-funded organisations providing disability and aged care services and private providers. We heard concerns that the non-prescription of such organisations has negatively impacted on risk assessment and management activities, increased the risk of relevant information not being shared across services and limited services’ ability to keep perpetrators in view. Particular concerns are highlighted below.

Commonwealth-funded services

Although some Victorian state-funded disability and aged care services are prescribed as ISEs and framework organisations, most services that are funded by the Commonwealth Government are not.

Notably, service providers funded through the National Disability Insurance Scheme are not ISEs or framework organisations under the Act. This means they cannot share risk-relevant information under Part 5A and are not required to align with MARAM under Part 11. Many stakeholders reflected that this has created a significant gap for victim survivors who have a disability. Stakeholders noted the importance of family violence information sharing and risk assessment for people with disability, particularly given “the intersection of women with disabilities and higher rates of their experience of family violence”.24 As explained by the Office of the Public Advocate:25

[G]iven that the funding and regulation of disability and aged care services has largely shifted to the Australian Government, it is concerning that no Australian Government agencies or funded services have yet been prescribed as information-sharing entities in respect of the MARAM Framework. Ultimately, prescribing them in respect of the FVISS and MARAM Frameworks is important to ensure early and accurate risk assessment and responses when concerns are raised about at-risk adults.

Safe and Equal agreed, highlighting the “strong need for a disability sector that has requisite family violence knowledge and the ability to appropriately share risk relevant information”.26

Stakeholders also highlighted the negative impact of non-prescription of certain services on older people experiencing family violence. For example, one stakeholder reflected that the non-prescription of aged care services “can create barriers to accessing relevant information about both victim/survivor and perpetrator, and may unintentionally expose older victims to higher risk of harm”.27

Private providers

Similar concerns were raised about the non-prescription of private service providers such as psychologists and psychiatrists. As noted by the Australian Psychological Society, non-prescription “appears to create a gap with information sharing and the ability for a psychologist to practically manage these issues from a legal perspective”.28 Monash Health similarly highlighted the potential negative impact on the safe discharge or transfer of care from a hospital setting to a private psychologist.29

We also heard concerns about the potential for the non-prescription of private providers to be used by some perpetrators to avoid accountability. This was best explained in the submission from No to Violence:30

[P]rivate professionals (such as counsellors) are exempt from the Act. While they may have the same role in addressing presenting needs of a perpetrator, they are not subject to the same legislation. It is important to consider that their clients are more likely to be comprised by those with higher incomes. When considering the principles of the Act in holding perpetrators accountable and in view of the service system, a risk exists that we are disproportionately monitoring those perpetrators with lower incomes (or with court mandated requirements through contact with the criminal justice system) while others with greater access to resources can keep themselves ‘out of view’. When we consider the intersections of economic class and other communities, it is important to consider how we don’t replicate existing oppressive structures.

Other concerns

Other concerns raised by stakeholders included that the non-prescription of financial institutions has impacted on the ability to investigate cases of financial elder abuse. Although not always raised in the context of the non-prescription of organisations, we note that some stakeholders also raised concerns about the lack of a family violence lens being applied by the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia. Stakeholders noted the potential for court orders permitting perpetrators to have continued access to child victim survivors. We have highlighted victim survivor concerns about the family law system in previous reports, including most recently in Crisis Response to Recovery Model for Victim Survivors.31

Rationale for not prescribing agencies

As part of phase 2 of the FVISS and MARAM reforms, the government considered prescribing a broader range of disability services, private allied health services, private aged care services, private hospitals, private psychiatrists, private psychologists and private education and care services.32 An analysis of the Regulatory Impact Statement that considered this option indicates that the decision not to prescribe such organisations was based on the following factors:33

- A significant number of organisations and services that would have limited readiness to comply with the requirements under the FVISS and MARAM reforms would be included.

- Organisations and their workforces would not have capacity to update their policies and attend training under the implementation timeframe for the reforms, which would increase the risk of inappropriate information sharing and potentially compromise victim survivor safety.

- Significant funding would be required over a short period to train workforces.

- Organisations not funded by the state government may have competing organisational priorities and different processes in updating policies and procedures, which may produce unknown and unintended costs if prescribed under the FVISS and MARAM.

- There are added legal, regulatory and other complexities in prescribing private providers and Commonwealth services that will require time and resources to resolve, with the costs incurred likely to be higher than usual due to the short timeframes.

As is evident from this analysis, much of the rationale for not prescribing additional organisations stems from constraints relating to the implementation timeline for the FVISS and MARAM reforms. We recognise these as important and valid factors in the decision not to prescribe organisations as part of phase 2 of the reforms. However, we equally note that these factors would not prevent organisations being prescribed in the future provided there was enough time for training and readiness activities.

We note that some other jurisdictions have prescribed Commonwealth-funded organisations for the purposes of their family violence information sharing laws. For example, in Queensland, information can be shared by and with a non-government entity funded either by the State or the Commonwealth to provide services to people who fear or experience family violence or who commit family violence.34

As previously noted, the prescription (or non-prescription) of organisations is ultimately beyond the scope of this legislative review. However, we consider it important that there be consistency regarding the prescription of organisations or programs that provide the same or similar services, and we are concerned about the negative impacts identified by stakeholders as a result of the non-prescription of certain organisations. We suggest that the government reconsiders the possibility of prescribing relevant Commonwealth-funded organisations and private providers to promote consistency and address gaps in information sharing and risk assessment and management.

Implementation of the FVISS and MARAM reforms

Stakeholders considered that some implementation issues have impacted on their ability to fully implement the Act

As previously noted, this legislative review focuses on the effectiveness of the legal provisions in Parts 5A and 11 of the Act, and we have not reviewed how government agencies have implemented the FVISS or MARAM reforms. However, many stakeholders spoke of several implementation issues that have impacted on their ability to implement the Act. These issues are noted below.

Funding and resourcing

Many stakeholders highlighted challenges related to the funding and resourcing needed to implement the reforms. Workforce challenges were also identified as issues negatively impacting on organisations’ ability to implement the reforms, including workforce shortages, high staff turnover, reform fatigue and the impact of COVID-19, as well as increased demand for services across the sector.

Some stakeholders expressed the view that funding had been insufficient for services to meet the requirements of Parts 5A and 11. Particular concerns were raised in relation to short-term funding cycles. For example, the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency explained that this creates “significant challenges which hinders implementation and genuine embedment of MARAM as a whole of organisation”.35 Safe and Equal similarly reflected that “the lack of consistent and ongoing resourcing has hindered the efficient implementation and alignment at times, which has in turn impacted the capacity of the reforms and the Act being safely and fully realised”.36

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners highlighted a particular funding challenge, noting that because there is no Medicare Benefits Schedule item number for family violence work, the time required for general practitioners to assess family violence risk and share relevant information is unpaid work. We highlighted this issue in our report Early Identification of Family Violence Within Universal Services and reiterate our suggestion that the Victorian Government advocates to the Commonwealth for creating Medicare items relating to family violence.37

Some stakeholders highlighted the need for extra staff to respond to information sharing requests, with common concerns including that responding to requests takes much longer than was originally anticipated and that it can be challenging to prioritise such responses over other client work. Similarly, stakeholders commented on the importance of having specialised staff to assist organisations to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the MARAM Framework. For example, Merri Health reflected:38

For a large organisation, the time and resources required to map responsibilities and training requirements for staff and update policies, procedures and position descriptions, is well beyond internal capacities and requires the investment of a dedicated worker to oversee MARAM alignment.

We heard positive examples from organisations that had received MARAM alignment funding. For example, Primary Care Connect shared that they could employ a full-time consultant to map roles and responsibilities across their program and found this to be incredibly valuable. However, they noted that they could not have done the MARAM alignment work without the funding. We also heard that many other services did not have the resources to employ dedicated staff to progress MARAM alignment in this way.

In highlighting potential approaches to address funding and resourcing challenges, some stakeholders suggested that the extra time required for organisations to meet the requirements of the FVISS and MARAM reforms should be reflected in services’ funding models. We support ongoing efforts to ensure adequate funding and support for ISEs and framework organisations, including through funding agreements where appropriate.

Practice guidance, training and professional development

As previously noted, Family Safety Victoria has developed resources and tools to support organisations to align with the MARAM Framework. They have also developed practice guides to support practitioners in understanding and applying their responsibilities under MARAM at a practice level, as shown in Box 11.

Box 11: MARAM practice guides

The Foundation Knowledge Guide is to be used by all practitioners to support a shared understanding of family violence across the service system.

The adult and child victim survivor–focused MARAM practice guides are to be used by practitioners supporting victim survivors.

The adult perpetrator–focused MARAM practice guides are to be used by practitioners working with perpetrators of family violence.

Source: Victorian Government, MARAM Practice Guides: Foundation Knowledge Guide: Guidance for Professionals Working With Child or Adult Victim Survivors, and Adults Using Family Violence (February 2021).

These guides were released at various stages. The Foundation Knowledge Guide and victim survivor–focused guides were released in 2019. An updated Foundation Knowledge Guide, incorporating new perpetrator-focused practice concepts, was released in 2021 together with perpetrator–focused practice guides for non-specialists. Comprehensive perpetrator–focused practice guides were not made available to specialist workforces until February 2022. New practice guides and tools for working directly with children and young people experiencing and using family violence are still being developed.

Stakeholders raised concerns about the phased approach to, and delays in, developing practice guidance. For example, the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency reflected that the phased rollout had “presented barriers to the smooth implementation and embedment of MARAM”.39 The delay in releasing the perpetrator–focused guidance and guidance for adolescents who use violence in the home posed particular challenges in working with, and assessing the risks associated with, such individuals. Other stakeholders told us about challenges associated with the need to continually update policies and practices, and retrain staff, every time new guidance is released. Although we acknowledge the likely impact of COVID-19 in contributing to delays in developing practice guidance, we support ongoing efforts to ensure guidance and resources are developed in a timely manner.

We also heard mixed views about the quality and availability of training for practitioners. Some stakeholders reflected that quality often depended on the individual training provider, while others considered that training quality has improved over time and has supported understanding of the Act’s requirements. We heard that it was challenging for some organisations to coordinate staff attendance at training, while others had difficulty accessing training. Concerns were also raised about the ability of services to progress MARAM alignment before receiving MARAM training.

Many stakeholders saw ongoing/refresher training and professional development as a key element in ensuring organisational understanding of, and compliance with, the provisions in Parts 5A and 11. Stakeholders also highlighted the importance of specialised and sector-specific training and resources to support implementation. For example, Early Childhood Australia Victoria Branch noted that there “is a demonstrated need to develop simple, practical, sector-specific resources for the early childhood sector”.40 Other stakeholders agreed that general training was insufficient and that specialist, tailored training was needed for individual sectors.

Some organisations that were not prescribed under the FVISS or MARAM also highlighted the benefit of broader access to MARAM training. For example, some community legal centres considered that legal services (and the justice sector more broadly) should have access to MARAM training to ensure best practice family violence service delivery that aligns with the family violence support system.

Client referrals

The availability of referral pathways in regional and rural areas, capacity limits within services and other challenges in referring clients to services were raised as additional constraints on effective risk management for victim survivors. For example, Sexual Assault Services Victoria reported that:41

[T]he overall pressure on the family violence response system in Victoria means there is often no one … to refer victim/survivors to when the potential service user is assessed as not in crisis but is not yet safe enough to engage in counselling. This leaves victim-survivors at risk and perpetrators unaccountable.

Particular challenges were highlighted in relation to victim survivors who use alcohol and other drugs (AOD), including due to the abstinence policy adopted in crisis accommodation services. As explained by the Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association:42

[V]ictim survivors that use alcohol and other drugs are routinely denied crisis accommodation due to their alcohol and drug use. This is a great concern as it places the victim survivor back in the household of the person using violence, and further disenfranchises them from the service system.

The Royal Melbourne Hospital similarly reflected that it can be challenging to provide referrals for people with multiple issues, such as mental health and AOD issues, presenting alongside family violence. Victoria Legal Aid also identified challenges referring adolescents who use violence in the home.

Information technology and secure storage of information

Services’ use of different information technology (IT) and case management systems was also highlighted by some stakeholders as a barrier to implementation of the FVISS and MARAM reforms.

Concerns about the adequacy of IT systems were also raised in the context of stakeholder confusion and concern about the secure storage of confidential information obtained under Part 5A. The Royal Melbourne Hospital noted particular challenges relating to information security in a hospital context, where family violence information may be contained in a patient’s file outside their room to support patient care on busy wards. The hospital has put in place measures to mitigate such risks. Sexual Assault Services Victoria also noted that “services are having to invest in developing their own IT systems to manage and store data, in order to meet legislative and funding requirements”.43

As recognised in the Ministerial Guidelines, keeping information safe and secure is a “critical part of managing risks to people’s safety”.44 As noted in Chapter 3, survivor advocates also highlighted the importance of protecting their information in keeping them safe. We note that under the Act all ISEs must ensure they handle personal information under Part 5A in line with either Victorian or Commonwealth privacy laws such as the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic).45 That Act requires the Information Commissioner to develop a Victorian protective data security framework and enables the Information Commissioner to issue standards for the security, confidentiality and integrity of data.46

Implementing reforms of the scale of the FVISS and MARAM takes time and requires ongoing and dedicated effort, noting that this legislative review was only able to measure that Act’s effectiveness after less than two years of operation for many ISEs and framework organisations

Many stakeholders commented on the scale of the FVISS and MARAM reforms and highlighted that, although progress has been made, full and effective implementation requires significant cultural and organisational change and will take time to achieve. Stakeholders also highlighted the importance of all prescribed organisations having implemented the FVISS and MARAM in maximising the effectiveness of the reforms. We heard that the reforms will only be effective if the entire system is working together.

The intent of the five-year review of Parts 5A and 11 of the Act was to enable an assessment of the effectiveness of the provisions after five years of operation. Noting the phased approach to implementing the reforms and the impact of COVID-19 on implementation timelines, we acknowledge that many organisations had only been prescribed for approximately 18 months at the time of our stakeholder engagement. This has meant that many organisations, particularly universal services, remain early in their organisational change journey. As a result, we have only been able to consider the extent to which the Act has been effective on the basis of a considerably shorter period than the five years that was envisaged.

In our view, it is important that there be a further review of the operation of Parts 5A and 11 once organisations have had time to fully implement the reforms. Noting the varied and significant implementation issues raised by stakeholders, we believe it would be beneficial for a further review to focus on the implementation of the reforms by ISEs and framework organisations. We therefore strongly suggest that the FVISS, Central Information Point (CIP) and MARAM reforms be reviewed again by the end of 2026.

Footnotes

- Victorian Government, MARAM Practice Guides: Foundation Knowledge Guide: Guidance for Professionals Working with Child or Adult Victim Survivors, and Adults Using Family Violence (February 2021). Although discussed throughout the guides, see in particular the following: sections 10.3–10.4, 10.6 and Chapter 12 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide; and sections 1.3.4, 7.9, 8.11–8.13, and Appendices 11 and 13 of the Working with Victim Survivors of Family Violence Guide.

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, Submission No 33, p. 7.

- The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre, Submission No 27, p. 7; The Salvation Army, Submission No 30, p. 6.

- Sue Leake Elder Abuse Liaison Officer (EALO) on behalf of the EALO's part of the Integrated Model of Care for Responding to Suspected Elder Abuse (IMOC), Submission No 42, p. 3.

- Monash Health, Submission No 13, p. 3.

- inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence, Submission No 41, pp. 5-6.

- The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre, Submission No 27, p. 7.

- Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), section 144QC. Note that the secrecy laws overridden by Part 5A are set out in Schedule 1 of the Act and regulation 15 of the Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018.

- Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 28 October 2020, p. 2979 (Jill Hennessy, Attorney-General).

- Children and Community Services Act 2004 (WA), section 28B(5).

- Victorian Government, The Cabinet Handbook (August 2021), pp. 10–11.

- The power for a court to issue a subpoena is generally outlined in the court’s establishing legislation. In Victoria, FOI requests can be made under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Vic).

- The Sexual Assault and Family Violence Centre, Submission No 27, p. 6.

- Victorian Government, Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines: Guidance for Information Sharing Entities (updated April 2021), pp. 130–131.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- No To Violence on behalf of the specialist family violence advisor capacity building program in mental health and alcohol and other drugs, Submission No 16, p. 8.

- McCulloch, J et al, Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme (final report, 30 May 2022), Recommendation 22.

- Victorian Government, Victorian Government Response to Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme (August 2020), p. 19.

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, Submission No 33, p. 4.

- Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (Vic), section 41ZA.

- Victorian Government, Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines: Guidance for Information Sharing Entities (2021), pp. 30-33.

- Ibid., p. 31.

- Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (Vic), section 41ZO.

- No to Violence, Submission No 26, pp. 7-8.

- Office of the Public Advocate, Submission No 32, p. 3.

- Safe and Equal, Submission No 44, p. 11.

- Sue Leake Elder Abuse Liaison Officer (EALO) on behalf of the EALO's part of the Integrated Model of Care for Responding to Suspected Elder Abuse (IMOC), Submission No 42, p 2.

- Australian Psychological Society, Submission No 39, p. 2.

- Monash Health, Submission No 13, p. 2.

- No to Violence, Submission No 26, p. 7.

- Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor, Monitoring Victoria’s Family Violence Reforms: Crisis Response to Recovery Model for Victim Survivors (final report, December 2022), p. 36.

- Victorian Government, Regulatory Impact Statement – Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Amendment Regulations 2020 (final report, 17 October 2019), p. 30.

- Ibid., pp. 35–36.

- Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 2012 (Qld), sections 169C–169E. Note that in Queensland the term domestic violence is used rather than family violence.

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, Submission No 33, p. 3.

- Safe and Equal, Submission No 44, pp. 15–16.

- Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor, Monitoring Victoria’s Family Violence Reforms: Early Identification of Family Violence Within Universal Services (final report, May 2022), pp. 28–29.

- Merri Health, Submission No 21, p. 5.

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, Submission No 33, p. 3.

- Early Childhood Australia Victoria Branch, Submission No 3, p. 2.

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria, Submission No 24, p. 1.

- Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association, Submission No 18, p. 1.

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria, Submission No 24, p. 3.

- Victorian Government, Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines: Guidance for Information Sharing Entities (updated April 2021), p. 131.

- Under section 144QB of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic), the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) applies to ISEs that do not otherwise fall within the definition of an ‘organisation’ within the meaning of that Act or are not subject to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

- Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic), Part 4.

Updated